Cultural Heritage Is Caught Up in the Conflict Over Nagorno-Karabakh

A priest fights to defend an ancient monastery after a quick, decisive war.

After being photographed with a cross in one hand and an automatic rifle in the other, Father Hovhannes became a viral sensation in Armenia. He says he never intended to become a symbol of defiance during the recent war over Nagorno-Karabakh, the region within Azerbaijan that has attempted to break away and declare itself the “Republic of Artsakh,” with the support of the Armenian government but no other forms of international recognition. “I was showing that we need both god and our weapons to defend our homes,” he says. “The book of our enemy allows them to take any land that they please.” He is the abbott of the stunning medieval monastery of Dadivank, within the disputed territory. He says he is prepared to die to defend it—but for the time being, he’s not able to be there at all.

Standing in the Monastery of the Holy Trinity on the outskirts of Armenia’s capital, Yerevan, Hovhannes is tall and broad-shouldered, with a thick white beard. His priestly collar pokes from the top of a thick black leather jacket, like a rock star who traded his guitar for the liturgy. His congregation treats him as such, crowding around him for blessings in place of autographs. Only his furrowed brow and downcast eyes betray his worries.

Dadivank, his monastery, is one of the greatest examples of Armenian church architecture, and dates to between 700 and 1,100 years ago. It is nestled in the forested ravines that make up Kalvajar region of Azerbaijan, around 125 miles away from where he stands. Until recently, it was controlled by forces loyal to Artsakh, but under the terms of a November 2020 peace agreement imposed after their bruising defeat in a war, it has been handed to Azerbaijani control.

“Not only is the monastery holy, like any house of god, it is a symbol of our Armenian identity as Christians that stretches back two millenniums,” he says. It is a great point of Armenian pride to have been perhaps the first Christian nation, and it is said that this heritage comes from this monastery specifically, founded in the first century by Dadi, a disciple of Thaddeus, the apostle who spread the Christian faith to the region. It has persisted through Mongol, Persian, and Russian dominion, as well as the two more recent wars over Nagorno-Karabakh.

This site was long believed to be the burial site of Dadi himself. This claim was thought to be folklore, until an excavation in 2007 appeared to uncover his tomb. For the abbott, who had overseen a project of painstaking reconstruction since the region’s capture by Armenians in the 1990s in the first Nagorno-Karabakh War, the find was a vindication of his efforts and beliefs. It appeared, to many Armenians, to be a confirmation of their historical claim to the land.

Dadivank is the most significant of hundreds of Armenian churches and historical artifacts that are in the process of being handed over to Azerbaijan. Hovhannes has serious concerns about its future. After the 1915 genocide saw Armenians expelled from Anatolia, successive Turkish governments systematically razed Armenian sites there. In the aftermath of the first Nagorno-Karabakh War, Azerbaijan destroyed hundreds of khatchars (uniquely styled cross monuments), a medieval cemetery, and around 90 churches.

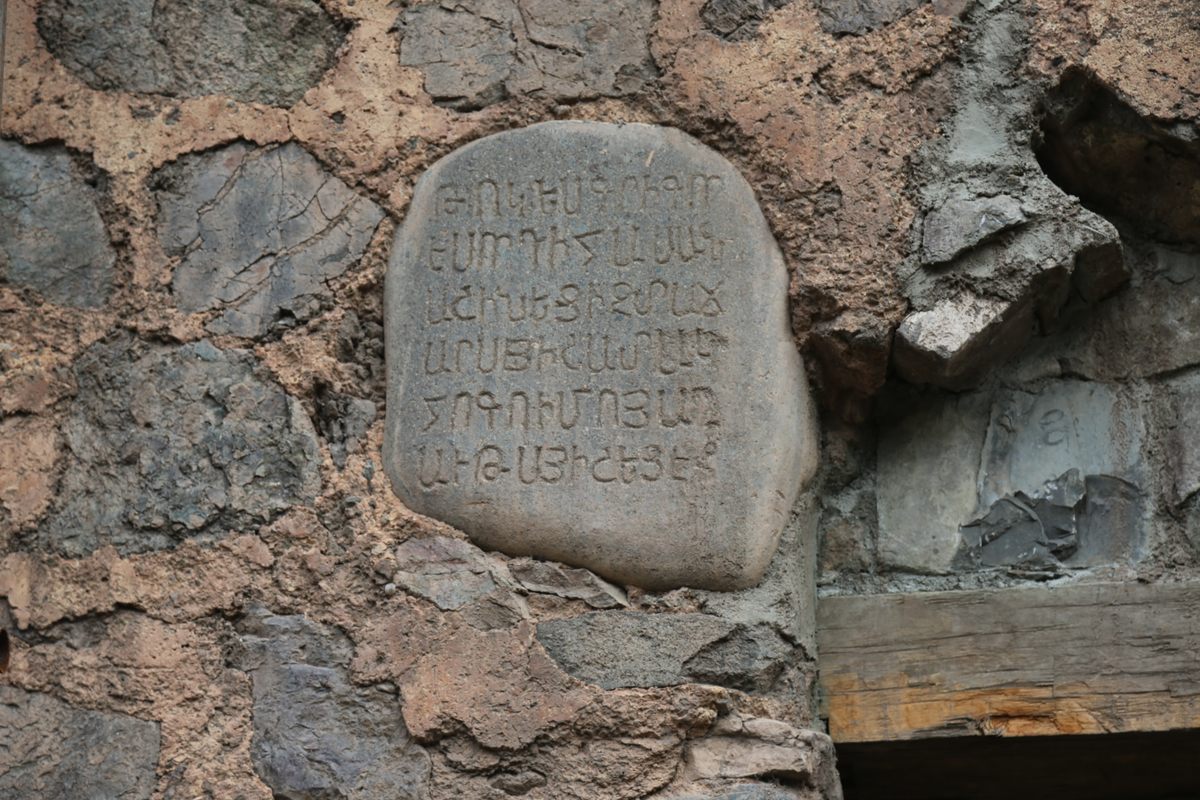

Astghik Pashinyan, a 29-year-old tour guide from Yerevan, made her last visit to Dadivank a few days before the handover. She describes the loss as “incredibly painful.” “The road was only recently fixed, so we have only just recently begun take tourists there,” she says. “They have all been so pleased with the beauty of the site and the hospitality of the locals. Now we believe the Armenian script and frescoes of the church will be destroyed.” She saw that Armenian soldiers had made preparations to move some of the church’s relics, including its bell and crosses, to Armenia to protect them.

Azerbaijani officials, including Culture Minister Anar Karimov, state—without specific evidence—that the church’s inscriptions, in medieval Armenian script, are fake, added in the 19th century. Instead, they claim that the site is a remnant of a little-known Turkic civilization called “Caucasian Albania,” which would make the region rightfully Azerbaijan’s. Most serious scholars find these tortuous explanations to be nonsense, as described in journalist Thomas de Waal’s Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. Neil Hauer, a journalist and researcher who specializes in the region, called it a “a straight up lie.”

On the other hand, Cavid Aga, a respected Azerbaijani scholar of the heritage of the Caucuses, points out that Armenians have also failed to recognize legitimate Azerbaijani heritage. “In Armenian historiography the Azerbaijanis are a people that magically appeared in 1918, they do not accept us as an authentic nation,” he says. “They label all Azerbaijani heritage as Persian or Turkmen.” He points out that heritage sites such as the Mausoleum of Turkmen Emirs in southern Armenia and the Yukhari Govhar Agha Mosque in Shusha, Azerbaijan, not far from the Armenian border. He says they have been misleadingly labeled by Armenians as having been built by foreign invaders, even though the people who founded them were from the area, and are ancestors of modern Azerbaijanis. “Even though the state of Azerbaijan was created at the end of the Russian Empire, that does not mean its people are aliens to this land,” he says.

In the moment, the preservation of heritage such as the church is less subject to competing claims than it is to the reality of power on the ground. For now, Russian troops are providing a temporary solution. The warring sides have agreed to a shaky deal whereby Moscow’s peacekeepers will protect the monastery and guarantee safe passage for worshippers. Every Sunday, Armenians who wish to visit can be picked up from the regional capital of Stepanakert and taken to the monastery under armed guard. It is an echo of the medieval Treaty of Jaffa, which ended the Third Crusade. Then, Saladin allowed Christian pilgrims to visit Jerusalem unharmed—in exchange for acceptance of Muslim control of the Holy Land.

Hovhannes does not believe the agreement with Azerbaijan, and its Turkish supporters, will hold. “Every bite they take just makes them hungrier. Now they want all of Artsakh.” he says. “Then they will come for all of Armenia!”

After speaking about his concerns in Yerevan, Hovhannes gathers his priests and the deacons for an evening service. Dressed in a variety of red, blue, and gold vestments, they recite prayers in melancholy voices in front of an image of the virgin and child. They read from Psalm 123: “Have mercy on us, Lord, have mercy on us, for we have endured no end of contempt. We have endured no end of ridicule from the arrogant, of contempt from the proud.”

Additional reporting by Ezras Tellalian.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook