See How Badly Crop Burning Is Fouling Northern India’s Air

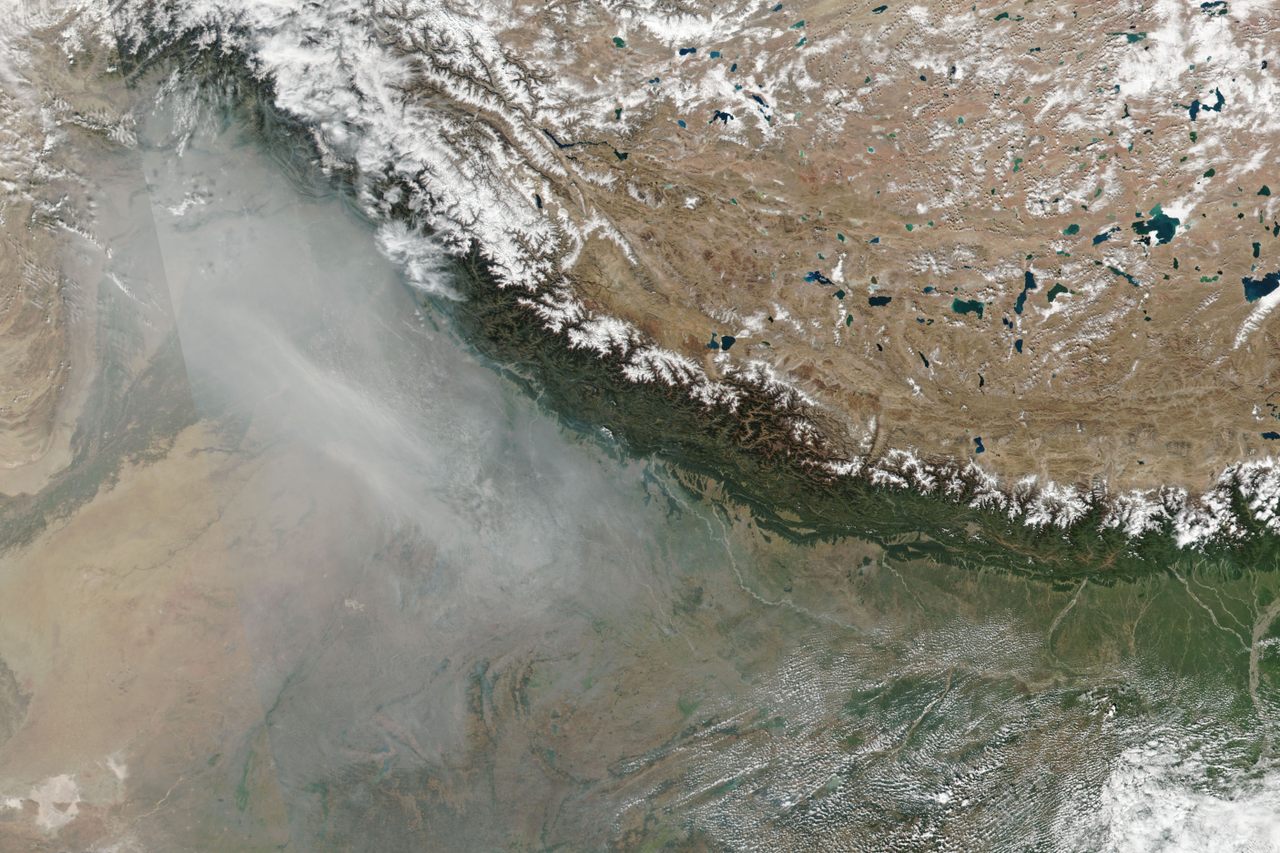

NASA photos show an impenetrable haze.

Diwali may be a festival of lights, but if often arrives amid an opaque, smoky haze. NASA has captured striking images of the thick smog consuming northern India on the eve of the festival, thanks to the agricultural burning prevalent in the states Punjab and Haryana after the autumn wheat and rice harvest comes to a close.

“Stubble burning,” as the practice is known, became common among farmers in northwest India in the 1980s, after the advent of automated combine machines that made farming easier but also yielded more debris. For independent farmers, the cheapest, most efficient way to get rid of tall leftover stalks is to set them ablaze, quickly clearing the fields for the next round of crops. Each operation may be relatively small, but together, they add up.

Last year, The Hindustan Times estimated that nearly 40 million tons of crops are burnt annually in just the two states—a dangerous part of what makes New Delhi the world’s most polluted megacity. Even measured against more cars and factories, the crop fires are significant. A Harvard University study found that when the fires peak in October and November, they can account for half of Delhi’s air pollution level—up to 20 times what the World Health Organization deems safe.

The practice is now technically illegal, but the ban is hard to enforce. A NASA satellite monitoring the Indo-Gangetic Plain, which runs across most of northern India, watched fires increase by about 300 percent between 2003 and 2017. The NASA images put into harsh perspective just how completely the fires clog the air, concealing vast stretches of the landscape from the satellite. Diwali revelers can only wait until the smoke clears—and wait for next year’s burning season.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook