How the Alchemy of Copper and Design Creates Great Gin

The history of this botanical drink is more spirited than you can imagine.

Sun-baked hay. A bustling Marrakech market. Pinecones on the forest floor. Though these may seem like prompts for a poem, they are in fact tasting notes from gin, a spirit with a history of being maligned and misrepresented. Perhaps worst of all for gin advocates though? It’s misunderstood.

“A lot of customers who don’t like gin have only consumed it with tonic,” says Brendan Bartley, bar manager at New York’s Bathtub Gin, which keeps 60 gins on hand. “The flavor profile of gin gets lost in translation, because most people don’t like tonic. It’s not the actual gin—gin has so many variants that there’s generally something for everybody.” Hence the 60 different bottles.

When it comes to what distinguishes gin from other spirits, the name itself offers a clue. “Gin” is a shortened version of the word “genever,” which has its origins in the Latin word juniperus, or “juniper.” That coniferous Christmas tree and shrub is an essential part of gin, as the spirit must draw its main flavor from juniper to be considered a gin in the United States. It also has to be fairly boozy. By definition, gin must have no less than 40 percent ABV (80 proof).

A stirred and sordid history

Centuries ago, gin tasted nothing like it does now as its swirled into Singapore Slings and mixed into martinis. Initially, it wasn’t even found in bars. In the mid 17th-century, gin was sold in Dutch and Flemish pharmacies, where it was thought to be an herbal panacea for everything from kidney problems to gout, and gallstones.

The gin-as-spirit craze didn’t really kick off until William III became King of England in 1689. He banned brandy, the drink of choice, and began offering tax benefits to British citizens who distilled their own spirits.

The free-for-all resulted in a gin distillation process that was, to put it mildly, disastrous. Turpentine, sulphuric acid, and sawdust were all involved in early iterations of the stuff, and gin was blamed for insanity, crimes, mania, and deaths due to overconsumption.

In 1830, Irish inventor Aeneas Coffey changed history with his patented still. It had two columns: one where the wash that would become gin was piped and warmed in copper wash-heaters, and a second where distilling took place. Suddenly, producing a clear, safe gin was not only possible, but popular.

Today, it’s only gotten more so: Even as alcohol consumption took a worldwide dip from 2017 to 2018, gin’s global consumption grew 8.3 percent, according to a 2019 report from International Wine and Spirits Research (IWSR). The drink’s popularity doesn’t show any signs of ceasing, either. Traditional gin is estimated to increase by five percent in the next four years, and industry experts say flavored gin will see a jump of around three percent.

Distilling takes on a new design

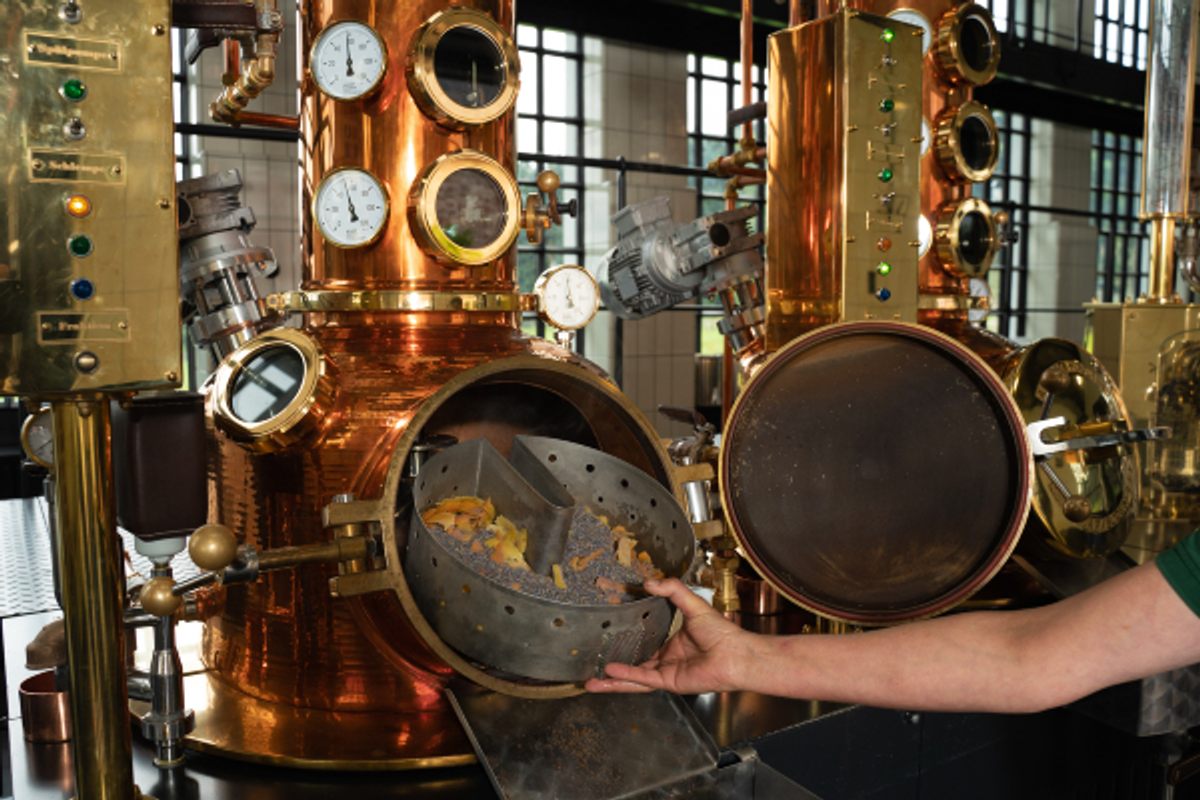

To make gin today, producers start with a neutral high-proof alcohol, whether it’s homemade or purchased. In the “one-shot” method, they then add the botanicals to the alcohol and draw out their “essences” by placing them in baskets exposed to steam. They can also put the botanicals directly in with the alcohol, and then dilute the mixture. The “concentrate” method, however, distills the botanicals separately with a small amount of water before mixing with distilled alcohol and water. (The “cold compound” method makes the cheapest gin by mixing botanicals with the neutral spirit, then filtering them out.)

Though fundamentals of still design have changed slightly, for purists, copper remains essential to transforming botanicals and neutral alcohol into gin. The metal is an excellent conductor of heat (second only to silver), keeping the temperature even through distillation. Copper also works double-time. It absorbs the sulfur produced during fermentation and yields a cleaner, smoother gin. So says Lewis Harsanyi, whose Los Angeles-based Bavarian Breweries and Distilleries provides companies with distilling systems.

As a soft metal, copper is also highly malleable, making it easy to manipulate and shape. Some of the most ornate copper stills in existence are built and hand-hammered by coppersmith Arnold Holstein, whose family has created custom distillation units on the shores of Germany’s Lake Constance since 1958.

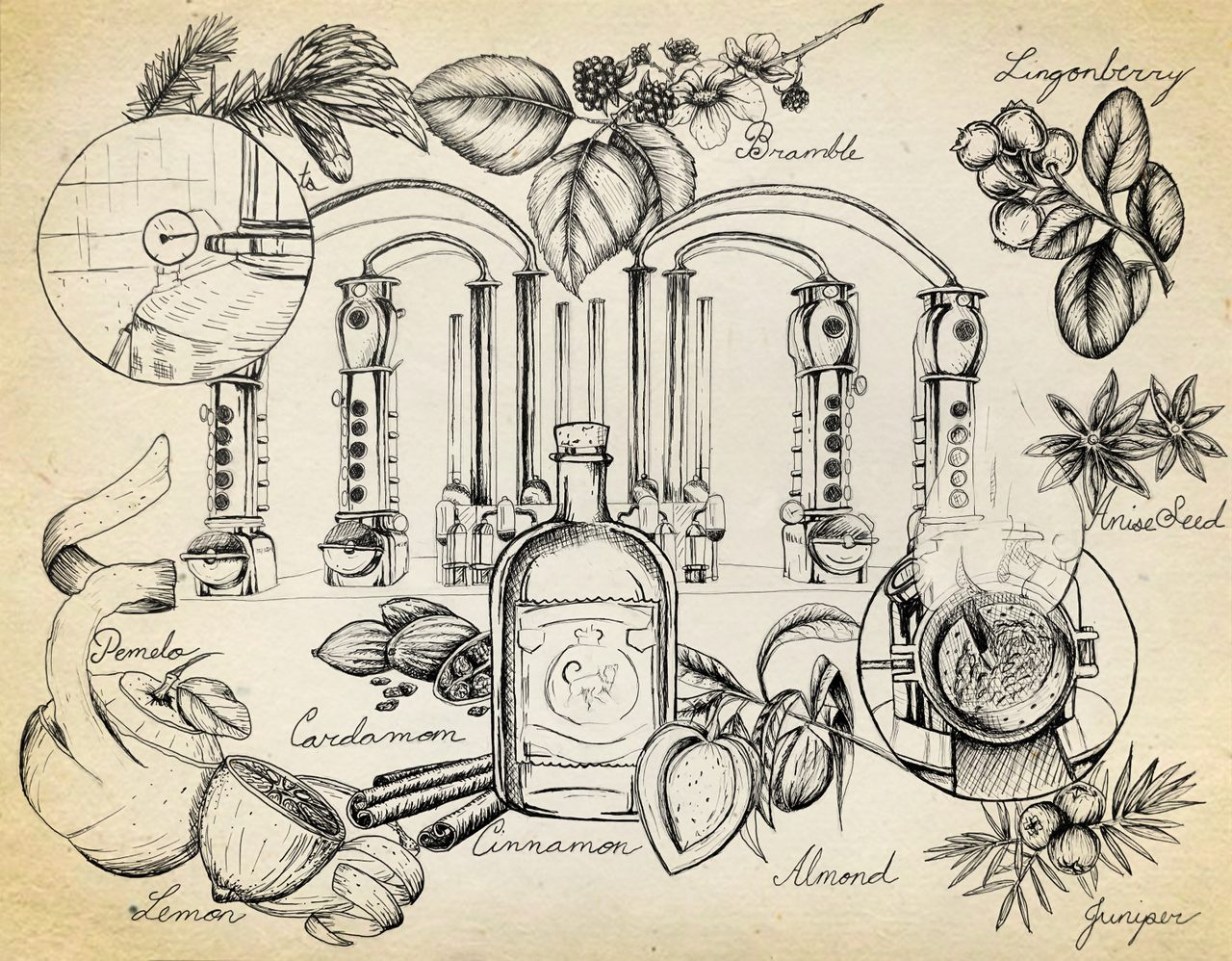

Monkey 47 Gin’s hand-assembled “Apparatus Alembicus Maximus” required two years of Holstein’s collaboration, design, and craftsmanship. The 100-liter still—intentionally on the smaller side to optimize the surface ratio of copper to mash—produces just 25 liters of gin at a time. That makes each run among the most limited still-made gins in the world.

Botanicals make the brand

In addition to copper, other factors in the distilling process affect taste, from the size and shape of the still to the rate at which the alcohol is allowed to “pass through” and steam the botanicals, and for how long. It’s this flexibility—and potential for creativity—that has gin advocates excited about the future.

Many distillers liken their pursuit of flavor to perfumers drawing out different aromas from ingredients. Coriander seeds, for example, give a gin citrus and spice notes, while dried orris root (the root of the iris flower) helps gin taste vaguely floral and licorice-like. Saffron can bring to mind breakfasts of cinnamon toast, while cardamom can recall a smoky, perfumed friend. Lemongrass in the mix? On the tongue, it may read as freshly mowed grass—but in a good way.

“When we say a word like lavender, it conjures up a very specific notion: perhaps of lavender soap, or the fields in France,” says Aaron Knoll, who has written two books on gin and has officially reviewed more than 600 gins for his website, The Gin Is In. “But when you distill lavender it tastes fundamentally different. It can have a mentholic, grassy flavor to it. When we distill these botanicals, they are transformed beyond recognition. Rarely do things literally taste like what we’re familiar with.”

Aside from juniper, there is no minimum botanical requirement in gin, and there is no limit either. In fact, Monkey 47 Gin, the German spirit mentioned above, gets its unique profile from an extensive list of 47 different flavorents: Lavender, fresh hand-peeled citrus, and rose hips all join juniper to make the gin floral, sweet, and herbaceous. Around one-third of the botanicals—like spruce shoots, bramble leaves, and lingonberries—are even foraged directly from the Black Forest, where the distillery (dubbed “The Wild Monkey”) has been operating south of Lossburg, Germany, since 2015.

Looking at the list of botanicals found on most brand labels will not only give you clues about the flavor, but a glimpse of the time when (and place where) the recipe was created. “A lot of the darker spirits [like bourbon, Scotch, and rum] have very similar tasting notes, because they’ve got wood on them, they’re barrel aged,” says Bartley. “Gin’s [flavor] is accordant with where it comes from.”

All gins may have juniper, but juniper itself has between 50-67 species growing primarily across the Northern Hemisphere. Juniper grew in popularity hundreds of years ago because it was ubiquitous in Europe. Citrus first started to join juniper in gin recipes around the 19th century, when fresh lemons and oranges were considered an alluring luxury item. Across gin today, makers are incorporating local botanicals—from hand-picked buchu in South Africa’s Western Cape to pink peppercorn found high in the Peruvian Andes.

Monkey 47’s dozens of ingredients are rooted in a recipe that traces its origins to 1951, when a man named Montgomery Collins left the Royal Air Force and moved to the Black Forest. Though Collins was first interested in watchmaking, the surrounding herbs and juniper inspired him to turn his attention to making gin. Decades later, Collins’ first Black Forest gin was discovered in a dusty, hand-decorated bottle in his guesthouse, which he had named “The Wild Monkey Inn” after adopting a monkey from the Berlin zoo. The long list of botanicals included alongside the bottle would later serve as the base of Monkey 47 Gin.

“No other spirit presents such a blank canvas onto which a distiller can tell a story about a place or a culture or a process, or paint this artistic vision,” says Knoll. “But if we were to narrow down the lens of what could be considered gin, I think we would be much poorer for it. Because I don’t think there’s another medium where people are learning so much about botanical diversity. There are so many things out there. And so there’s no end in sight.”

This post is promoted in partnership with Monkey 47 Gin.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook