Alternating Currents

The rise and fall of Venezuela, as seen from a Colombia border city, its grand mosque, and the migrants and converts who worship there.

It’s 3:20 in the afternoon when the adhan echoes across Maicao, Colombia.

The Arabic call to prayer flows through the sun-baked streets, lined with street vendor stands stocked with plastic bottles of contraband gasoline, smuggled across the nearby border with Venezuela. Crowds of migrants fleeing their country’s turmoil fill the marketplace in the central plaza.

Towering over it all is the source of the call, the Mosque of Omar Ibn Al-Khattab, named for one of the most prominent figures in Sunni Islam, a companion of Muhammad. It is easily the small city’s most prominent landmark.

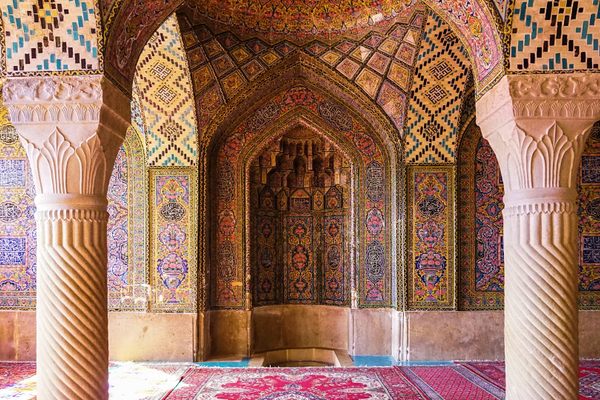

Star-shaped aqua and purple stained glass windows adorn the Italian marble facade, and palm trees and violet flowers burst from small gardens flanking the doors. Cream-colored arches and pillars encircle the 101-foot minaret, which reaches into the cloudless desert sky in three stacked stages like a fountain. From the street, the large central dome is barely visible beyond the cornice that crowns the building.

It’s one of the biggest mosques in South America—some say the second, others the third. Regardless of where it falls on the list, it rivals the mosques in the continent’s biggest cities: Buenos Aires, Caracas, Bogotá. The building was once packed with the community of Lebanese immigrants who made up a significant portion of the population.

“Twenty, thirty years ago, this community was one of the most representative Arabic communities here in Colombia,” says Pedro Delgado, a researcher who works with the National Center of Historical Memory, headquartered in Bogotá, to document the history of the country’s Muslim population. “The mosque was the center of Islam in Colombia. That’s what it represented.”

The city of 160,000 in the country’s northeastern desert has long been defined—culturally, economically, even spiritually—by cross-border trade with Venezuela, which is what had drawn the Lebanese community there. In recent years, the border has continued to define Maicao, but in a different way, as successive tides of violence and the exodus of Venezuelans fleeing the country’s deepening, all-encompassing crisis have swept through. This desert border city now bears the weight of the 21st century: civil conflict, corruption, international trade, criminality, inequality, economic collapse, mass migration.

As the adhan rings out across the dust-filled streets, this building, a monument to a community, feels more like a relic. The thriving migrant community that constructed it is mostly gone, replaced by another.

The shop of 55-year-old Nabil Elneser, a leader of the Colombian-Lebanese community, lies in the heart of Maicao’s mish-mash of markets, a stone’s throw from the mosque. Elneser stands attentive, near rows of shoes and sunglasses. His carefully groomed beard extends to the collar of his pale, ankle-length thawb. He wrings his fingers around his misbaha, a set of green prayer beads, as he talks to customers examining a pair of shoes. Elneser’s grandparents were some of the first Lebanese migrants to settle along the Carribean coast in the 1910s, and made their way to Maicao in the 1950s.

During World War II, migration from what today are Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria—then part of the Ottoman Empire—surged in the face of growing repression and violence. In Lebanon, as the global powers vied for regional control, many saw escape as the only alternative. Places such as Colombia, Panama, and Venezuela presented the potential for both safety and economic opportunity.

“They had two options: stay there in the war or migrate across the world to search for prosperity,” Elneser says.

Colombia caught a significant part of that wave from Lebanon: the golden city of Cartagena, tropical Santa Marta and Barranquilla (home of Colombian-Lebanese pop star Shakira), and Maicao, gateway to the sere, windy La Guajira Desert on the Caribbean coast, just west of the Gulf of Venezuela. La Guajira is a place of rolling dunes, bright blue seas, and scattered brush. Then, as now, the larger region has been marked by deep poverty, minimal access to fresh water, and the presence of the Wayuu indigenous people, whose territory straddles the northern stretch of the Colombia-Venezuela border.

Maicao didn’t seem to present much potential then. It was tiny, dominated by the Wayuu, and lacking in markets and other signs of thriving commerce. Without shops, a community, or support, the Lebanese migrants began knocking on doors to sell textiles and other goods in the stifling heat.

“They were growing, little by little, many were selling their commodities door-to-door,” Elneser says. “That was how they really built Maicao.”

Families chose trades based on the region of Lebanon they had come from. Some, like Elneser’s, focused on textiles. For others it was home goods, women’s clothing, perfume, shoes. But knocking on doors was not how the community grew prosperous. What made Maicao an appealing destination was its proximity to both a nearby seaport and the border, which is less than nine miles away, with the much larger city of Maracaibo a couple of hours drive beyond that.

“At one time, Maicao depended upon Venezuela because all of their trade expanded,” Elneser says. “One could say that the beginning of Maicao was tethered to the border.”

Customers waited on the other side, multicolored Venezuelan bolívars in hand, or crossed over to descend on Maicao itself and feast on its cheap goods. At the height of Maicao’s trade boom in the 1970s and 1980s, buyers might travel back and forth across the border multiple times a day. As Venezuela’s economy grew to become one of the largest in Latin America, so did Maicao’s in its second-hand way, and with it, the businesses of the Lebanese migrants.

The flow across the border went that way for years—cheap goods passing through Colombia and the hands of Lebanese merchants, to the eager, flush Venezuelan buyers. The border made the city’s identity then, just as it is remaking its identity now.

“The history of Colombia and Venezuela has been intertwined for centuries,” says Geoff Ramsey, Venezuela expert for the Washington Office on Latin America, a D.C.-based nonprofit that focuses on social and economic research and advocacy in the region. They meet across nearly 1,400 miles, the longest border for both countries. “Traditionally when the fate of one country is better than the other, there have been swings of migration over the border.”

Maicao, even during its most prosperous years, was always rather lawless. The city is at the end of a long road, through difficult country that was once dominated by armed paramilitary and guerrilla groups. The government generally took a hands-off approach. Delgado describes it as a “paradise of illegality.” There was corruption at all levels of government and business, drug trafficking, and widespread smuggling. Through all of this, the Lebanese community continued to do business and grew cozy with the power brokers of the city.

“These lands didn’t have any kind of regulation by the state or any kind of social or political substance to stop the corruption here,” Delgado says, biting into a piece of zataar bread in one of the city’s few remaining Arab restaurants. With minimal government presence, any existing policies were hard to enforce, he explains. “The only way to survive was to bring products from outside.”

The porousness of the border here, which runs through brushy desert, paved the way for the rise, in particular, of a petroleum-based contraband empire. Drugs, arms, liquor, knock-off clothing, textiles, and more landed, unregulated and untaxed, at the port. They would be met by smugglers and the Wayuu, who were critical to the enterprise. Because they lived on both sides of the border, they could pass through freely, without documents. Some of the goods would be pushed into Venezuela immediately and some would arrive in the interconnected street markets of Maicao, which grew to become a department store of contraband, including gasoline smuggled from across the border.

By the 1960s many of the business in the city weren’t registered with the government, and about half of those that were didn’t comply with payments to the local treasury, according to Diego Castellanos, a researcher at the National University of Colombia who studies Latin American Muslim communities. Venezuela’s oil boom in the 1970s added more fuel to the fire.

“In one moment, Maicao was a great commercial showcase of Colombia, because of the free ports it had,” Elneser says—free by practice, at least, if not in the eyes of the law.

In the 1970s, Lebanese migration to Maicao surged, as civil war tore Lebanon apart and the Venezuelan economy crested with rising oil prices that transformed the country. During this time, Venezuela had the highest rates of economic growth in all of Latin America. Its fortunes predictably turned when oil prices plummeted and its economy was severely mismanaged in the coming decades.

The migrants from the Middle East began to make over large swathes of the city. In the Arab neighborhood—literally, “barrio Arabe”—on the city’s southeast side, tower blocks—resembling those the Lebanese had left behind in cities such as Beirut and Tripoli—began to rise, looming over the rest of the city. Arabic graffiti mixed with the Spanish on the walls, and Middle Eastern markets popped up to serve freshly made zataar bread, baklava, and shwarma. Every morning, the storefronts under the apartment complexes bustled.

“Basically they started to recreate themselves, build themselves up, reproducing the familial structures that they had in Lebanon,” says Castellanos. At its height, approximately $2 million was produced every day from trade in the city, and the Arab community numbered between 8,000 and 10,000.

Mohamed Waked was part of that wave. The large-set Lebanese migrant—his friends fondly call him “El Gordito”—arrived in the city in the 1980s to get a foot in the perfume trade. “Arabs, we’re merchants,” he says, his Spanish layered with a thick Lebanese accent, afternoon sweat darkening his carefully tucked striped polo. “I saw there was this business and I came to be a part of it.”

Despite not speaking Spanish when he arrived, Waked made the border—and its collision of cultures—his own. He worked with Colombian, Venezuelan, and Wayuu businesses, and passed his evenings at a soccer field, where bearded Arabs would send puffs of hookah smoke into the crisp desert air, while Colombians and Lebanese men played heated games nearby. He married Mariam Zapata, a Colombian woman, and together they built a cross-cultural family.

Today Waked greets visitors at the carved wooden doors of the Mosque of Omar Ibn Al-Khattab, and often spends the sweltering afternoons locked in lengthy conversations about Islam in a corner of the vast prayer hall.

“There is this very beautiful mix between Arabe and Colombiano,” he says.

When the first Arab migrants arrived in Colombia at the end of the 19th century, they were largely Christians, who found themselves able to assimilate with relative ease in the largely Roman Catholic country. Maicao’s primarily Sunni Muslim community, most of whom came in the subsequent waves, had more difficulty.

“The Muslim Arabs didn’t find mosques, they didn’t find a Muslim community so they had to build it,” Delgado says. “And the first community that constructed itself in the Carribean coast was Maicao.”

As it is for many Muslim diasporic communities, cultural differences could be troubling. After the September 11 attacks, the Colombian media began to circulate what Delgado calls fearmongering stories about Maicao Muslims and their connection to Hezbollah and international terrorism. The divides in custom, religion, and, in many cases, language place an invisible barrier between these Arabs and the place they consider home. The sociologist Castellanos says that even though many of these families have been in Maicao for two or three generations, they still may be treated as outsiders.

Zapata, Waked’s wife, says that she’s struggled with those divisions, even in the only country she’s ever known. With a bright smile, she says she was raised Christian but converted to Islam early in adulthood, after she moved to Maicao for work. She began working with the Arab community around her, talked about Islam, and began to pick up religious texts. She felt a connection, she says.

But when she started wearing her hijab on the streets, she was harassed. “Often, they don’t understand,” she says. “They reproach you without actually knowing what Islam is. Because to wear a hijab is not to be a terrorist. They believe it’s like that, but that’s not the way it is.”

As the Muslim community in Maicao grew—in both size and prosperity—it began to look for what it still lacked: a place to convene, somewhere permanent and indisputable. “The community lacked somewhere they could pray,” Waked says. “There was once a place, but it wasn’t organized like a mosque. It was just a room.”

With donations from groups both inside and outside the local community, the Iranian architect Ali Namazi was brought in to design and build a towering mosque, big enough for everyone. While exact costs are not known, the mosque is estimated to have cost the equivalent of roughly $3 million today—quite a sum in the distant reaches of rural South America.

What locals call “La Mezquita”—simply “The Mosque”—was completed in 1997. Inside was a 1,476-square-foot prayer hall that can fit 700 men at a time, and a separate zone on the second floor for women to pray.

A mix of religious texts in Spanish and Arabic line the room. Marble pillars on the edges stretch up to the brightly colored, intricately decorated dome. In the early years, during Ramadan there were lines so long that many never made it in by prayer time and had to pray outside. At that moment, in the late 1990s, the mosque was a monument that granted the community a feeling of substance and belonging. All of which, almost from that very moment, began to unravel.

Maicao today is not what you’d call an optimistic, forward-looking city. Its gaze, as always, is toward the border, but has grown desperate, melancholy, tense.

Beaten-down rickshaws and motorcycles buzz through dusty streets, around trash piles and the occasional stray cow or goat. The market booths of the central plaza are packed like sardines, offering knock-off clothing and shoes, colorful woven Wayuu bags, electronics, fabrics, and juices of Colombia’s vast array of fruits. Venezuelan migrants sit in clusters—families, shoeless, pregnant women and young men with their hands out—hoping to scrounge enough for a bus ticket to just about anywhere else. Most of them had paid criminal smugglers to get them across the border on trochas, the same dirt pathways used for contraband. Maicao has always been fed and drained by the flow across these routes.

Outside the buzzing main square, signs of life are more scarce. Much of the city seems abandoned or at least eerily quiet. The shops of the Arab neighborhood remain boarded up, or open for a few fleeting hours. Violent crime is a serious concern, with only the most desperate or dangerous lingering outside at night.

Although it has been difficult to track over the years, the Arab population of the city has plummeted to an estimated 800, perhaps a tenth of what it was. The mosque remains, but few pass through its doors, even during Ramadan.

Hussein Omais Barrera, 42, lounges alone in the back of his empty electronics shop. He looks bored. He answers lazily when an occasional passerby pops a head in to ask after the price of a microwave or one of the fans he has arrayed against the wall. He says he has watched, year by year, as his friends and family have trickled away, headed for Barranquilla or Panama—or back to Lebanon.

He was born in Maicao to a Colombian mother and a Lebanese father who had fled his home to start a clothing business in the late 1970s. He grew up in the border city, but has spent large periods of his life living in Lebanon as well. He was there when the mosque was being completed. That was when his brother called, entreating him to return to Maicao to run a business together.

“I thought about staying in Lebanon,” he says. “But my brother told me, ‘No, I need help here in my store. Come here, it’s better.’”

It was, for a time. Goods flowed freely, at least until the government began to eye greater regulation, followed by bloody paramilitary conflict that put immigrants in the crossfire.

Left-wing guerrilla fighters from the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia–People’s Army, better known as FARC, clashed for control of the La Guajira region with the right-wing, drug-trafficking United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia, known as AUC, and other groups. It was a conflict in which kidnapping, extortion, and assassination were tactics of choice. The local Arab community, known business figures, were targeted.

“You would wake up and hear that in a nearby street they killed two or three people,” Delgado says. “We learned how to coexist with the news of kidnappings, of extortions, of robberies. For us, it was normal here.”

The researcher Delgado writes that the first of a string of kidnappings began in 1996. For years Arabs in Maicao were at risk of being snatched from the street or home, and could be held captive for months. In one case that he has noted in his writings, a preschool-age girl was taken on her way home from school.

The community, already wary and introverted, closed ranks. The neighborhood that was an expression of their roots became a refuge—or a kind of prison. The poorer in the community had Wayuu guards, while the richer went the paramilitary route. Slowly at first, the flows of migration began to warp. Many Lebanese, including Omais’s friends and neighbors—as well as the brother who had convinced him to return—left.

When the violence began to ebb, Venezuela, the country that had once been the economic fuel of Maicao, began to spiral downward.

When President Hugo Chavez took the reins of the country in 1999, Arab merchants say, his policies and social programs were good for business in Maicao. But corruption soon infected that process, and Venezuela’s oil-rich economy began to tank. Hyperinflation turned those coveted bolívars into little more than scraps of paper.

Businesses reliant on cross-border trade, including that of Omais and other Lebanese merchants, began to falter and then fail. Maicao’s golden days, including the surge of optimism that built the mosque, became little more than a distant memory. The border again exerted its control over the city and its residents.

As conditions in Venezuela grew more dire and basic services, food, and any sense of security evaporated, the exodus began—now more than four million people. Because of its proximity to Maracaibo, Venezuela’s second largest city, and strategic location along a major channel out of the country, Maicao saw a crush of migrants hoping for jobs, shelter, and food. They found a city that could barely hold itself together.

“When you have a million people flood into your country from a neighboring country it causes all kinds of ripple effects,” says Ramsey, of the Office on Latin America. “And there is a risk of local economies not being able to absorb such large numbers.”

The Venezuela-Colombia border has long been active—both in trade and in human movement. At one time Colombians flocked across in search of work and to flee the civil conflict that characterized the country for more than a half-century. With the reversal, the border city was inundated by a new wave of migrants, and the previous group that had come there—from much farther away, but also to seek opportunity and escape violence—closed up shop. In place of their once booming businesses are stalls selling those plastic liter bottles of gasoline, many smuggled by foot over the border.

The most recent estimates put the number of migrants from Venezuela in Maicao at 60,000—nearly 40 percent of the city’s population, far greater than the Lebanese population at its peak. In place of worrying about customers or even kidnappings, Omais says, there’s a fear of crimes of desperation. “I am scared, for the situation and safety in Maicao,” he says. “Criminals can arrive at the house of whichever Muslim or Arab and kill them for mil pesos [about $0.30], a cellphone, or whatever it may be.

“I miss Lebanon a lot,” he says. “Of course, I would return, and if I could in this exact moment, I’d go right now .... But I can’t go now because of the issue of money. There isn’t any.”

The last signifier of prosperity is the Mosque of Omar Ibn Al-Khattab, still open, still gleaming in the desert sun, still a beacon to people in the city.

Rosamarianis Ferrer, a slim, 41-year-old woman with skin that speaks of long days in the sun, pulls on a chador at the entrance of the mosque. As it falls over her dusty clothes, Ferrer describes how she, a Venezuelan from Maracaibo, ended up here.

She had left nearly a year before, as protests raged and the political opposition, today led by interim President Juan Guaidó, clashed with the military, controlled by Nicolás Maduro, Chavez’s successor. She wasn’t able to feed her four children, so she left them with her mother and crossed into Colombia illegally through the trochas. In Maicao, as many have done, she works odd jobs and began buying and selling everything she could—from clothing to toys—from her home to make money to send back to her family.

“To be separated from my children, yes of course, it’s hard,” she says. “I got used to being away little by little. But at first it hit me incredibly hard.”

Ferrer was going through that difficult time when she first entered the mosque. She says something drew her in. Raised Catholic, she struggled at first to understand the beliefs and traditions. But she learned and spoke with people and returned to the mosque again and again. She says it brought her a sort of hope as her home continued to descend into chaos. So she chose to convert.

“It’s something emotional to have some more clarity,” she says, peering up at the pale marble building, “to make better decisions, and it helps to carry these things with calm, with more tranquility.”

But calm and tranquility don’t seem to be in the cards for Maicao or the border region in any larger sense. Ramsey says the crisis in Venezuela has no end in sight, and the Organization of American States predicts that the mass migration from Venezuela will reach eight million by the end of 2020. That is currently second only to the wave of people who had fled Syria during its ongoing civil war (many of whom have ended up in Lebanon).

“If Maduro were to leave tomorrow, the country [will continue to be] in a complete economic state of collapse,” Ramsey says. “And that’s going to take years to recover from.”

The community leader Nabil Elneser, watching the situation continue to evolve and devolve from his shop, is not sure that Maicao or his community is ready for that.

“We’re not prepared for this,” he says, “just like the country isn’t prepared for this.”

You can join the conversation about this and other Border/Lands stories in the Atlas Obscura Community Forums.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook