My First Journey: Atlas Obscura Co-Founder Dylan Thuras’s Eastern European Adventure

“That context, that deeper understanding, it stays with you.”

To celebrate our 10th anniversary, Atlas Obscura is launching First Journey, a chance for one of our readers to win $15,000 toward a meaningful, once-in-a-lifetime experience. The competition is inspired by our co-founders, Dylan Thuras and Josh Foer, who both went on transformative journeys in their early adult years.

Though Josh and Dylan’s trips were very different, their approaches were the same: a clear mission, unrestricted time to explore, and deep, purposeful examination of a place and its cultures. Without these experiences, there would not be an Atlas Obscura. Below, I talk with Dylan about his First Journey, and you can also read my full interview with Josh about his journey.

So Dylan, what was the first real journey that you took in your life? Tell me about it.

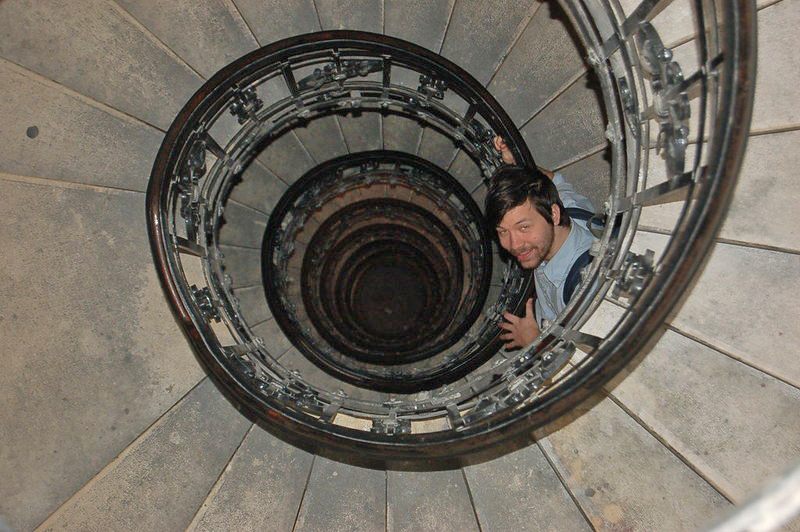

My first really transformative travel experience was more like a move. When we were in our early 20s, my wife and I moved to Hungary to live in Budapest for a year. Ostensibly, we were going to teach English as a second language, but what we really ended up doing was spending most of our time exploring Eastern Europe and teaching ourselves how to be photographers and writers. And kind of coming to understand what this sort of travel could be. It was a really formative experience.

How long did you end up staying in Hungary?

It was just about a year. It was over 2007 and 2008.

And the initial idea was that you were going to use these teaching positions as an excuse to really explore the region?

It was, that was the idea. Initially we thought we’d do it with video—that was our background, we were both video editors. At a certain point it proved more sensible to shift to photography and writing. But yes, we knew when we left, that this was going to be a chance to do something totally different, to explore.

And you guys started a blog during this time, right? What was it called?

It was called Curious Expeditions. I believe the tagline was, “Traveling and exhuming the world’s extraordinary history.”

Did you have a sense that that act of documenting and sharing what you found—that it propelled you both to explore in a particular way?

I had traveled before, as had Michelle, we both liked to travel and were excited to just see new things. But the thing that made it really different is that we had set up this framework of telling stories, of finding these places and pulling out some historical story or some detail to focus on, and then sharing that with a public audience. And through having that responsibility and having the framework, we had to research, we had to really understand context, to dig in.

If we saw some detail that we didn’t understand, we had to spend time going back over that after the trip to try to understand what that placard was saying, or translating things that were in another language to really get the context. And it just started to transform the entire experience from one of passive viewership to really active engagement with all these places we were visiting, with their history, with the way all of these things interconnected.

We started to form a more cohesive picture over the year, for example, how the Austro-Hungarian Empire shaped the entire region in which we were living. And that emergence of greater context made each trip, each next story we were working on, that much more revealing. It was a of sense of peeling back layers and not just seeing the thing, but developing a deeper understanding of it.

I’ve heard you describe Curious Expeditions as a kind of proto-Atlas Obscura.

It’s funny, we were sort of operating in parallel to Atlas Obscura. Atlas Obscura didn’t exist yet, it was just an idea—we had worked to build a prototype but then we’d scrapped it and had to start again after I got back from Hungary. But essentially I was working on the first few hundred Atlas Obscura entries while I was living in Hungary. I was able to kind of practice what we were hoping to preach with Atlas Obscura. I honestly think if we hadn’t been doing that, hadn’t been working on Curious Expeditions, hadn’t done all that travel and had those real “ah ha!” moments of stumbling across something incredible… Like I remember coming across Galileo’s middle finger, which is still a good Atlas entry.

A classic.

That’s one that is almost identical to the entry we wrote up for Curious Expeditions. I remember coming across it and being like, “what the heck—what have we just found? Why is everyone not shouting about this? Why is this not more of a thing?” And that feeling, it really animated me coming back and gave me the energy to understand what Atlas Obscura could be.

How did you organize your trips outside of Budapest, or even your days exploring the city? What was your approach?

We brought with us a surprising amount of books. We had some travel guides that had a sort of weird bent to them, and we had an out-of-print book called Weird Europe that we used. We had a few other general country and Eastern European travel books. So, we would do this kind of cross referencing. We would look at everything, come up with a list, and try to find more information, from the books along with what was available online at the time, which was, as I recall, not a lot. And then we’d make a plan based on the country. So, we’d say, “Okay, we’re going to try to make a Romanian trip, where do we want to go? What are some things that we think we really want to try to see?”

Sometimes we’d find, in a Lonely Planet or something, or a traditional guidebook, we’d find a one-sentence note in the additional material where it’s like, “there’s also a natural history museum in this university.” And I suspect the writer had never been there, but just knew that it was there. And we’d say, “Okay, we know we’re interested in kinds of all natural history museums in this region, we’ve had good luck when we’ve gone looking for these things before.” And then we’d take the trip.

Is there a particular moment or story from that time that you always tell, that was one of those “ah ha” moments?

One of my favorites was in Bologna. We had developed, over time, certain beats. So medical museums became like a beat. Natural history museums became a beat. And saint relics became a beat. And so, when we were in Bologna, we had heard that there was a saint relic there for St. Catherine of Bologna, and we went out to find it. We went in this church and there was like a little grill, a little circle opening with grating on it, and we realized that if you squinted through it you could see, in the distance, this face, this saint relic. And we thought, “well, there it is, sort of disappointing, there’s not much information here.”

We were getting ready to leave, and we saw that there was a little door with a doorbell next to it. So we rang the bell, the door slid open seemingly magically, by some sort of rope system, and no one was there. It just opened and you walked into this room. And it was sort of an antechamber, and then in the room, sitting in this golden throne, is St. Catherine of Bologna, who has been there for over 500 years and been taken care of by the same order of nuns for this entire time. She was obviously really cared for, and there were other saint bones around. And we sat on the floor and hung out with this saint relic, which was a moving experience. It was a quiet moment of communion. And there was another little door—I don’t know how to describe it—like a little sliding slot came open, and there was a nun back there who handed us a pamphlet. That was the whole thing, and then we left.

It was one of these experiences, with a series of reveals, and then at the end of it was this kind of quiet, contemplative moment where you thought about death and religion and belief and all this kind of stuff. And that for me was definitely one of the times that I really remember from the travels.

It sounds like the door with the doorbell was something you could have ended up easily overlooking.

Oh yeah, absolutely. I mean, we were a little hesitant to even ring it because we weren’t sure. You know, we didn’t want to make anyone angry. But I think we’d also learned over time, that it’s worth taking small risks of that sort of order to figure out if it’s worth it. But yeah, you could easily walk by it. I think most people probably did.

So, always ring the bell.

You’ve got to ring the bell! You’ve got find the weird little door!

It sounds like the fact that you had the opportunity to set up your life in this way for almost a year, to really devote yourself to exploring an entire region in a particular way, had a really profound influence on you.

Absolutely. Both Michelle and I describe it as kind of—I mean there are different formative experiences in your life, but I think of it as the single most formative at the time. It established a sort of worldview.

I think I’ve just intuited this from you after working with you for a couple of years, but I get the sense that you also have a life-long connection to that region, and it’s pretty personal for you. You really had an experience that will stay with you forever.

Definitely, that context, that deeper understanding, it stays with you. I do feel connected to Eastern Europe and the Balkans.

When you two travel now—obviously, you have kids now and your life is different than when you were 24—but are there rituals, or ways you organize or approach going someplace new, that you still take with you from what you learned during that time?

Totally. We just did this two-day road trip up to Maine. We had to come up here anyway, and so we said, “all right, what are we going to try to see?” And we went up to Vermont and we had a list of a bunch of places that are already in the Atlas, but I hadn’t been to them. And the trip reminded me of—there’s just no substitute for actually going to these places. We went to this one place called the Museum of Everyday Life in Vermont, and it’s this delightfully quirky museum.

There’s no one there, you’re on an honor system, so you turn on the lights and there’s a sign that says “please turn them off when you leave.” And you go in and look around and it’s a kind of meta-museum where a lot of regular stuff has been curated in very clever and funny ways, and it’s just a wonderful art project.

We also went to a natural history museum called the Fairbanks which is incredibly beautiful. But the one that really jumped got me was the Dog Chapel, also in Vermont. I knew about it, I’d read about it, I might have even written or edited the Atlas Obscura entry for it at some point. So, I felt like I was familiar with the story. But when I got there I was struck by how incredibly beautiful this place is. It’s a tiny church made by illustrator, painter, and sculptor, Stephen Huneck, who was obsessed with dogs. He wrote children’s books that featured dogs, and then he built a chapel that was for people and their dogs to come. He’s since passed away, and the chapel has become a pilgrimage site where people go to post notes and pictures to their deceased dogs and cats.

The walls are papered from ceiling to floor, in every room, with layers and layers of love notes to deceased pets. At first, I was just looking around like, “oh, this is a really interesting place, it’s beautiful.” And then I stopped and read these notes. The place became this overwhelming, absolutely beautiful testament to this pure love that people have for their pets, for their dogs, for their cats. So, being there transformed this place. I left with such a deeper affection and interest in it.

Traveling as a family is always going to be a push-pull of like, “how much can we fit in? When do we need to get the kids out?” But I still think the quest to get to the place, to understand it more deeply, is hardwired into both Michelle and I now. And you know, hopefully we don’t slowly teach the kids to hate travel.

That would be kind of perfect though, right? They’ve got to rebel against something.

It would be, exactly. [Laughing]

So Atlas Obscura is launching First Journey, a competition where we’re going to help somebody who’s got a great idea to go and take their own first journey. Why do you think it’s important for more people to have the opportunity to take a meaningful journey like you did?

I think there’s just tremendous value in giving yourself the space and time—and in some sense giving yourself permission—to not just travel, but to quest for understanding. Because it does take time and it’s slow, and it’s not about covering ground. In fact, it’s really about doing the opposite—to travel slow enough to let the deeper stuff bubble to the surface.

That might be kind of a convoluted answer, but I guess what I’m getting at is that a real journey is both external, going somewhere and seeing, but also an internal experience too. It’s a personal experience. And everyone comes from a different place. Everyone comes from a distinct set of experiences, and each person is going to bring that to their journey. And if it really is a journey, I think it can both result in wonderful storytelling but also a personal transformation, personal discovery. And I think that’s important for everyone. It’s necessary, for having wonder in the world.

I’ve been thinking about this a lot, and I don’t think I’ve ever really done it myself. I’ve taken trips, and I feel like I’m relatively well traveled, but I don’t know—I don’t think I ever really gave myself permission to have that kind of slower experience that you’re describing. Whether it’s that I didn’t feel comfortable taking the risk, or just didn’t have the resources, or I ended up on a career track, I’m not sure. But I think there’s something to that, about giving yourself the permission.

I think that’s absolutely right and it is really hard, no matter who you are, what age you are, you do have to really actively create the opportunity to have an experience like that. And in a way, I think it’s even harder now, because social media is such performative work. So people get stuck performing and kind of feeling like they’ve got to produce even in their leisure time. Giving yourself permission—I don’t know if we’ve done it again honestly, except in short little bursts, since then.

Totally, well, it’s hard. Everybody’s got to pay rent and, you know, have food.

We were incredibly lucky. We graduated right before the big recession, and we just happened to find ourselves in this position as young people with a little money in the bank and kind of a plan. But that’s not an easy place.

What are your feelings about the possibility that we might be able to help one of our readers have this type of life-changing experience?

I think it’s about as a good an outcome as one could hope for. It’s wonderful—and I think in a lot of ways the whole point of Atlas Obscura is to function as permission to take some of these journeys and explore things that you might not otherwise explore.

So to have the ability to expand that and say, “Okay, take a bigger journey, take a real deep dive into something, that maybe only you can do, maybe you’re the only person.” And that is beautiful not just for the person and the change that might come to their life, but also everyone else on the receiving end of the story that they tell. That is the beauty of giving someone a chance to step out of the locked-in paths that everyone ends up on and truly pursue something based on a sense of wonder, of curiosity. And see what comes of it.

Win $15,000 for your First Journey. Enter now.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook