When the CIA Spied on American Citizens—Using Pigeons

The seemingly birdbrained Cold War experiment is still partially classified.

Flying above the Washington Navy Yard, a spy was taking a series of pictures that revealed more than even the most advanced satellites, while the workers below went about their day-to-day lives, not knowing they were the subject of an espionage mission. Looking to gain an edge in the Cold War, in 1977 the Central Intelligence Agency had recruited a new, nearly invisible agent: a pigeon.

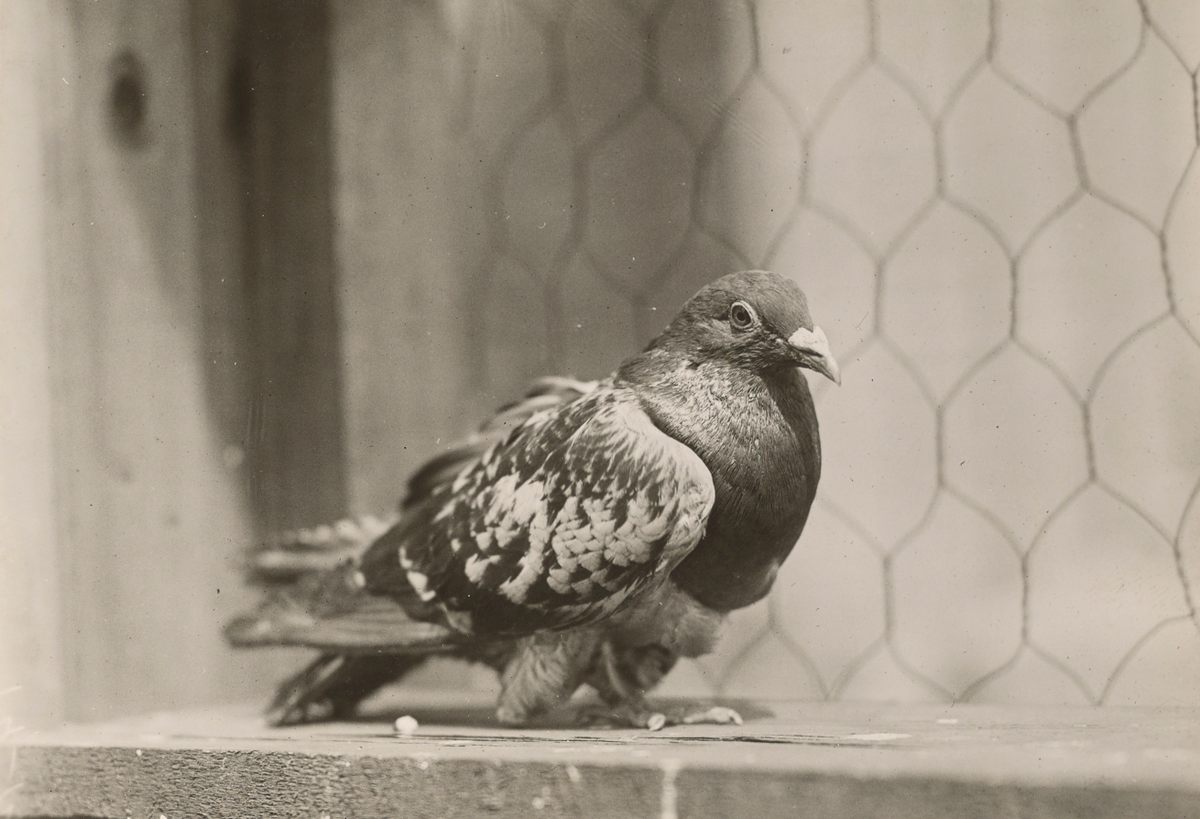

It may sound unusual, but the idea of using pigeons for espionage wasn’t without merit. The place of pigeons in an army was first recorded by the Roman historian Pliny, who described their role in communication, and the German army in World War I were the first to explore the use of pigeons for reconnaissance. The United States military had itself been using pigeons since the late 1800s for communication, but “I could not document any instance of them being used for reconnaissance,” says Elizabeth Macalaster, author of War Pigeons: Winged Couriers in the U.S. Military, 1878-1957.

Enter the CIA. “For several years, the Office of Research and Development [ORD] has carried out endeavors…to train different species of birds,” states a declassified September 1976 CIA working paper. However, until January 1976 the avian programs had been, “dismissed…as an improbable, exotic, humorous idea.” This opinion changed when someone realized birds could potentially be the answer to an ongoing problem: photographic coverage of sensitive areas such as naval yards in Leningrad.

“We didn’t have the opportunity in so many cases to get so close,” James David, curator of National Security Space at the Smithsonian Institution, told me in an interview about the history of the CIA’s Cold War satellite program. Maybe the pigeons could.

The project quickly ballooned in scope. By September 1976, the ORD had already invested $100,000 not just training pigeons, but designing harnesses and cameras for the operation. Testing and training were conducted throughout the United States. Various methods of releasing the pigeons were trialed, including modifying a VW Beetle to transport the birds; taking inspiration from stage magicians, the CIA cut a hole in the floor of the Beetle, allowing for pigeons to be surreptitiously released. By October 1976, the birds were flying over Andrews Air Force Base near Washington D.C., and in February 1977, the CIA proposed a further feasibility test at the Navy Yard in Southeast DC.

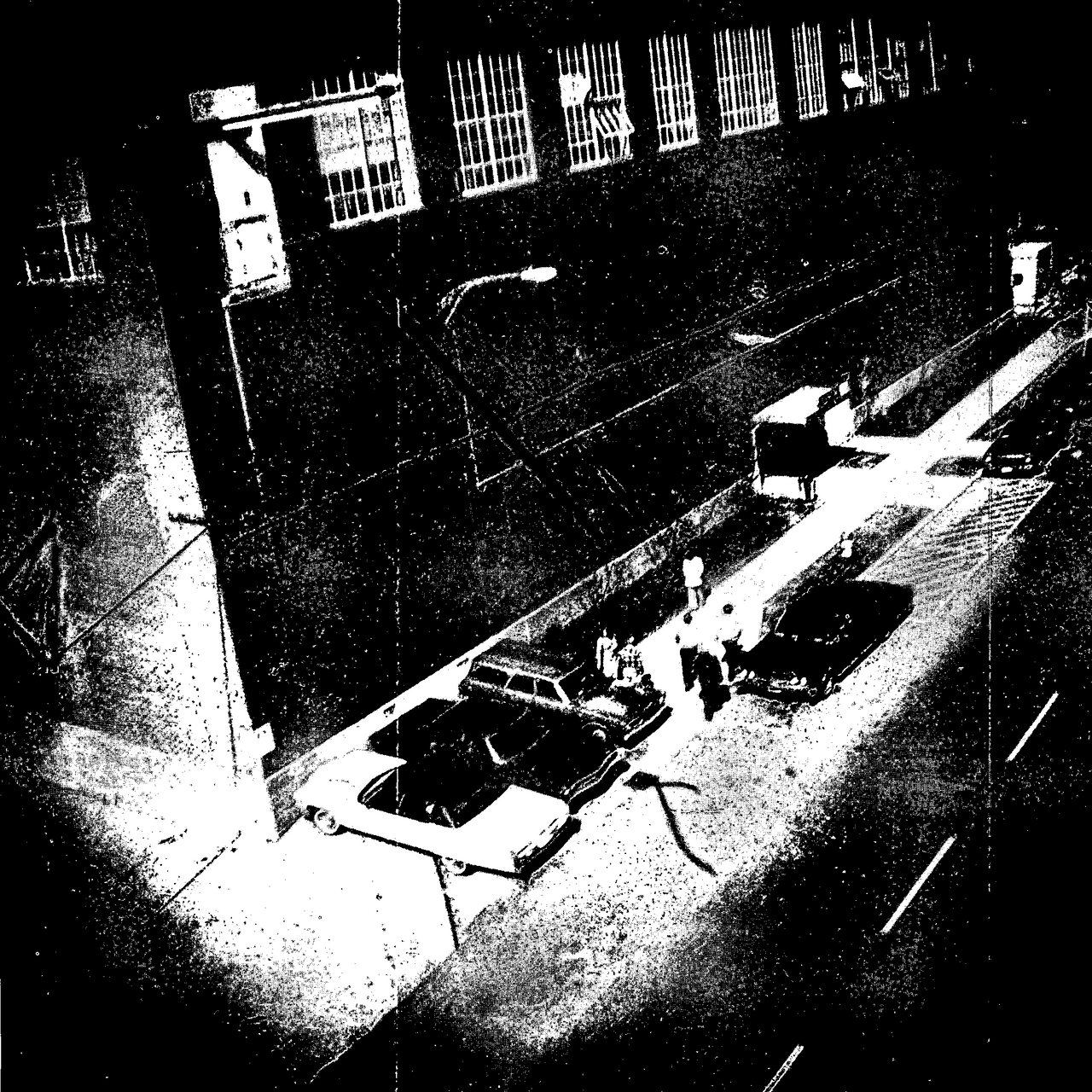

The Navy Yard was a bustling center of activity. Ceremonial docks mingled with active docks for ships under repair. Parking lots along the Anacostia River were filled by employees who worked for the United States Navy, the United States Marine Corp, the National Photographic Interpretation Center, and more. The iconic entrance to the facility, the Latrobe Gate, has remained unchanged since 1881. It is immediately identifiable in pictures taken by the clandestine pigeons.

The images the birds captured—since declassified by the CIA—were of astounding quality. Air conditioners could easily be seen on top of buildings and it was possible to count the window panes on the old Naval Gun Factory. The full resolution capabilities of the state-of-the-art American spy satellite GAMBIT-3’s are still classified, but it is known that it could spot an object as small as four inches square. “In comparison with [GAMBIT-3] photography of the same target,” reads a CIA report, “the avian system was rated as having a higher image interpretability as well as the ability to see smaller objects.” The pigeons could provide a resolution of ¾ of an inch.

Where the GAMBIT-3 was like using a magnifying glass, the pigeons were the equivalent of using a microscope. This high quality made it possible to see people in these images. In one of the declassified images, government employees can easily be seen walking to work. It is possible to make out the shape of the headlights on their vehicles. Their clothing with the styles of the ‘70s are easily visible.

While it can be debated that a certain level of privacy is forfeit while on a military installation this is explicitly not the case outside their gates. A tantalizingly small number of photos by the pigeons have been declassified, some of which show homes outside the Navy Yard. In 1975 the CIA had been castigated on the front page of the New York Times for experimenting on Americans. The details released by congressional investigations, as reported by the National Security Archive, concluded the CIA had “violated its charter for 25 years,” through “illegal wiretapping, domestic surveillance…and human experimentation.” It had not even been two years, and the CIA had turned Americans into unwitting test subjects again.

The declassified files end in 1978. A lengthy April 1, 1978, report stated that the program met the “high-resolution requirement” and was feasible—provided more testing was conducted. Others in the CIA did not agree. A memo labeled the program a “mess” that hadn’t proven anything, and it advised against adoption. But the extent of the program remains unknown; the most recent public comments by the CIA come from a 2021 video, advising, “parts of the mission are actually still classified.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook