These Cherokee Cave Inscriptions Describe a 19th-Century Stickball Game

The competition took place on April 30, 1828.

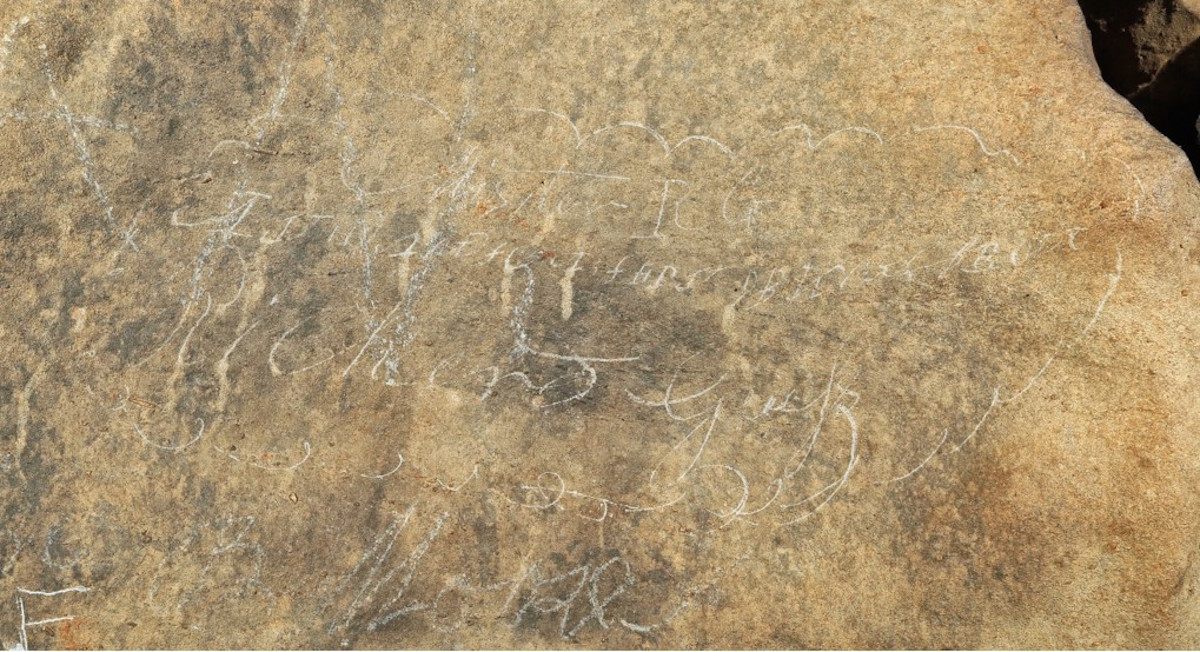

Thirteen years ago, a historian and a photographer working in Manitou Cave, on the side of Lookout Mountain in present-day northern Alabama, recognized a set of Cherokee inscriptions on the cave walls. This week, translations of those inscriptions appear in the archaeology journal Antiquity. According to those translations, the inscriptions are a unique record by the Cherokee of a ceremonial stickball game that took place in and near the site.

“When I went in this cave it kind of got me—it didn’t feel like the people who were writing on the wall were from hundreds of years before us,” says Beau Carroll, who translated the inscriptions, with the help of Cherokee scholars, for his master’s thesis in anthropology at the University of Tennessee. “It felt like it moved from their hands to my eyes,” he says.

A Cherokee himself, Carroll grew up playing stickball—a ceremonial game resembling lacrosse whose indigenous name roughly translates to “the little brother of war,” according to Julie Reed, a Cherokee historian at the University of Tennessee. Some of the inscriptions inside the cave commemorate a stickball game played on April 30, 1828.

More than a game, stickball is a ceremony of cosmological import, requiring intense preparation and attention from the players under the supervision of a Cherokee doctor. Preparation includes ritual scratching, during which small incisions are made all over the body and herbs applied. It also involves meditation and ritual cleansing before and after the game in a water source.

During the game, players use arm’s-length sticks with a hand-sized cup on the end to run balls to goalposts, usually marked by a pair of trees or branches. Stickball could be used to prepare for skirmishes, to settle conflict in place of battle, or simply as an excuse to have a good time and gamble a little. Whatever the purpose, it tends to be bloody. In stickball, there are few formal rules, and no boundaries.

Growing up, “we usually played at an annual fair,” recalls Carroll. “Once we ended up in somebody’s food stand—there were 10 people in this woman’s food stand rolling around and fighting.”

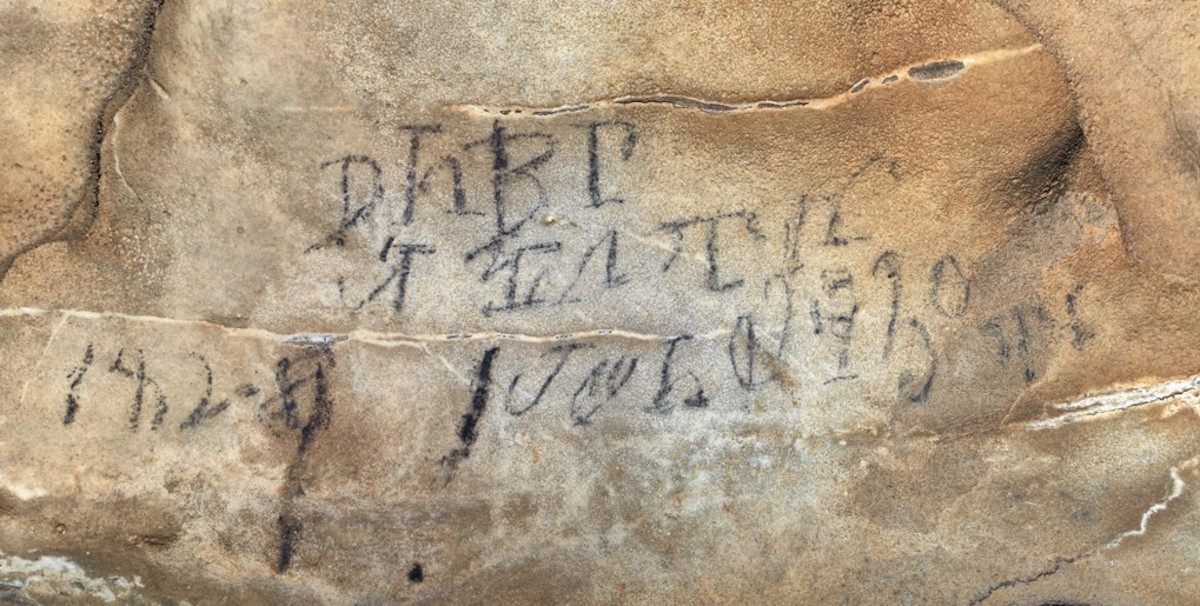

Manitou Cave was once a tourist attraction, but was abandoned in 1979. It is now in private hands and closed to the public. The writing stands somehow untouched by the later graffiti crowding around it. Nearly a mile into the wet darkness of the stalactite-and-stalagmite-filled cave, above the origin point of an underwater stream, the date of the stickball game is inscribed along with the words, “We are those that have blood come out of their nose and mouth,” and, “I am a respectable man of authority,” below which is the signature of Richard Guess, one of Sequoyah’s sons.

Sequoyah, a Cherokee scholar, developed the Cherokee syllabary, a writing system comprised of 85 distinct syllables, in Willstown after moving there with his family from Eastern Tennessee in the early 19th century. Willstown is located near Manitou Cave and is known as Fort Payne today.

The syllabary was introduced to the Cherokee community in 1821 and formally adopted in 1825. By 1828, it had even been adapted for letterpress printing and was used to publish a newspaper, The Cherokee Phoenix, which later became The Cherokee Phoenix and Indians’ Advocate, to reflect its concern with tribes beyond the Cherokee.

The syllabary was created at a critical juncture in U.S. government policy towards indigenous Americans. Fearing reprisal after siding with the British during the American Revolution, many Cherokees had moved westward to Willstown in the early 19th century, but they couldn’t escape encroachment. At that moment, there was “this promise that, if you become civilized enough you can be part of who we are,” says Reed. This “civilization process” included adopting Christianity, learning to read and write in English, changing traditional farming practices, and even shifting the roles of men and women. “On the one hand, Sequoyah’s process is in line with that idea, that intellectual capacity is supposedly what sets apart savages from the civilized,” says Reed. “On the other, doing it in the Cherokee language allows old practices to continue.”

Even in 1828, Manitou Cave was remote, making it an ideal place to practice traditions that were inconsistent with the demands of missionaries and governmental authorities. Carroll surmises that Guess was a doctor who led the ceremonial rights for the game that day, including the ritual cleansing, which would have used the underwater stream in the cave. Like his father, Guess was a community leader; when forced relocation began along the Trail of Tears in 1838, he was hired by the federal government to help ease the process for other Cherokees as they were moved to concentration camps.

For Carroll, studying the inscriptions has been a way to learn more about historic practices, and forge connections to this past. “When I practice my religion,” he says, “I’m doing it the same way as the person who was writing on the wall.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook