Why Wartime England Thought Carrots Could Give You Night Vision

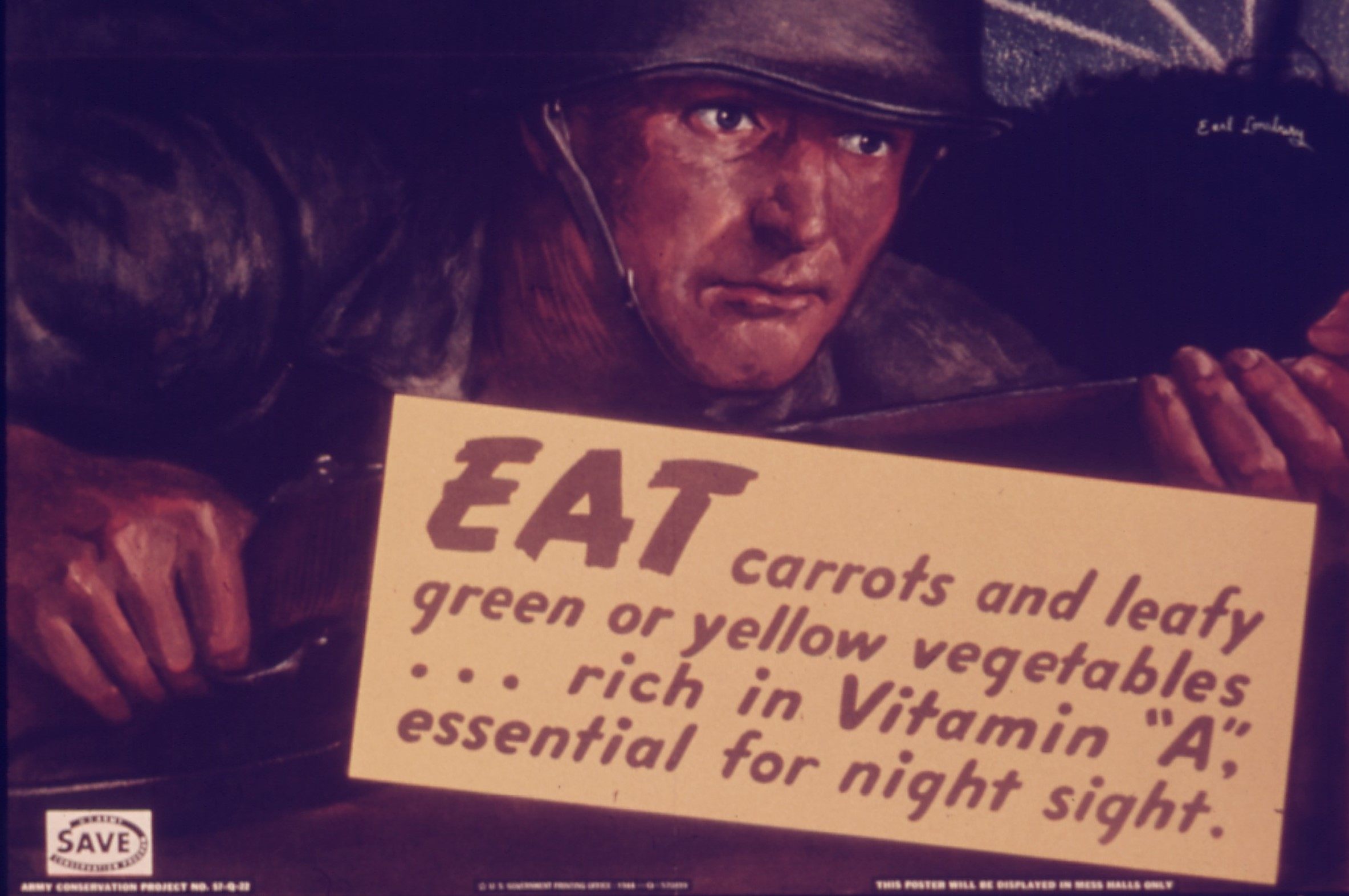

The belief that carrots improve your eyesight dates back to World War II propaganda.

Children have long been urged to eat carrots in order to improve their vision. But a carrot-filled diet won’t get you 20/20 vision or help you see in the dark. That idea is a legacy of World War II, when the British government—aided and abetted by Walt Disney—told Britons that eating carrots could sharpen their eyesight and help win the war. The message resonated beyond its borders, and it’s still persuasive today.

There is a link between carrots and eyesight. Carrots contain beta-carotene, which helps produce the purportedly eye-boosting Vitamin A. However, it doesn’t actually sharpen eyesight. What Vitamin A can do is cure night blindness, a disorder that makes it difficult to see in low light. Although night blindness is sometimes caused by cataracts, in cases where it’s caused by Vitamin A deficiency, carrots are one way to save the day.

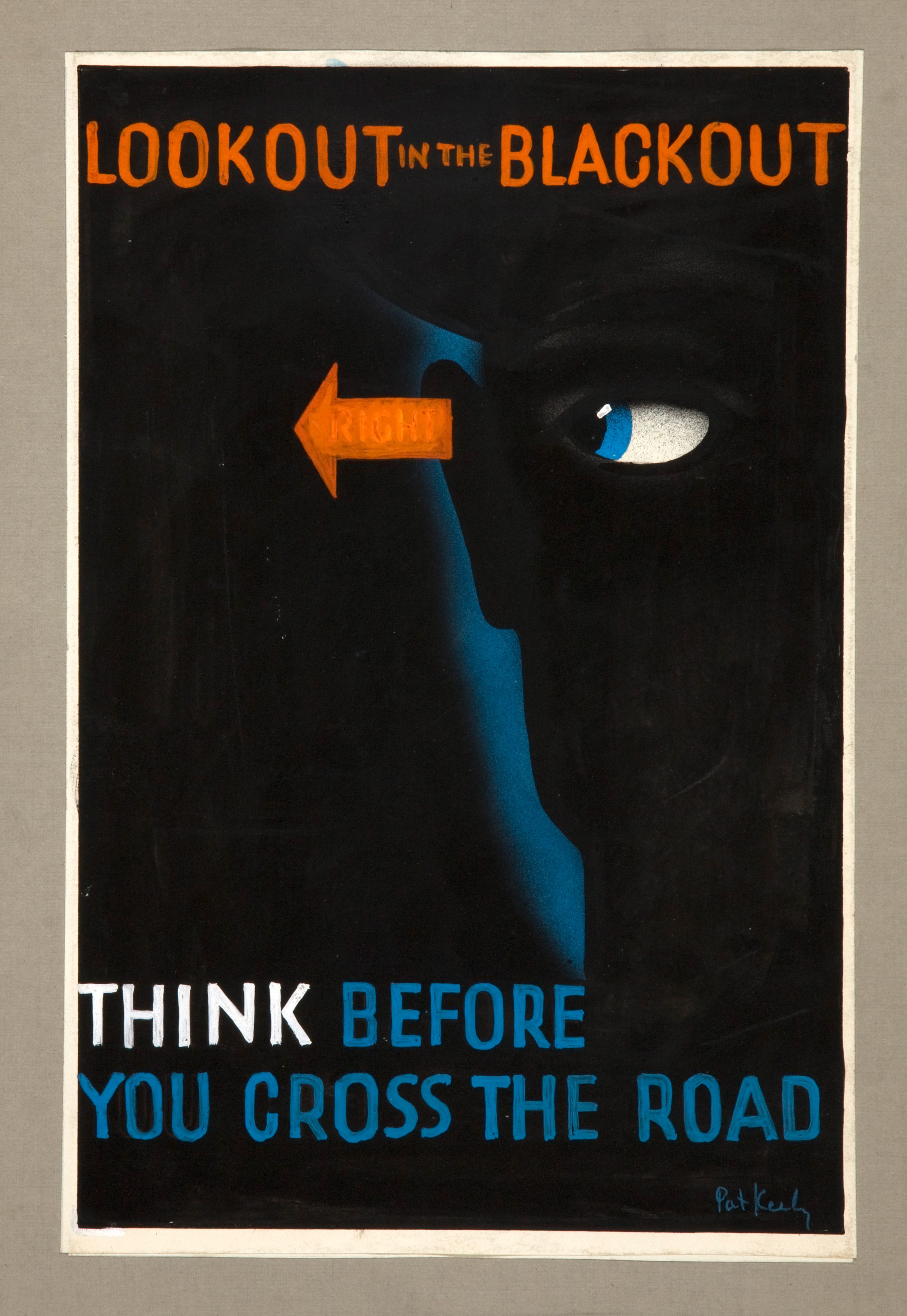

During World War II, Great Britain had good reason to be concerned about night blindness. To foil raids by German bombers, who targeted the lights of towns and cities, England went almost totally dark at night. The blackout lasted from 1939 to 1945, and the lack of light caused accidents. In the first month of the war alone, the blackout likely caused 1,130 road deaths.

On December 22, 1940, the British Ministry of Agriculture released a statement urging the populace to eat carrots. “If we included a sufficient quantity of carrots in our diet,” the statement read, “we should overcome the fairly prevalent malady of blackout blindness.”

But the government had another motivation in pushing carrots: Great Britain faced food shortages due to wartime rationing, and carrots were plentiful and cheap. This led government agencies to tout them as having eye-strengthening powers as part of widespread campaigns aimed at getting the British public to eat carrots.

Radio spots and film reels humorously extolled carrots. Grim posters plastered around cities implied that only by eating carrots could people dodge darkened cars. Britain’s Ministry of Food even published pamphlets with recipes such as carrot fudge and carrot croquettes, while proclaiming the vegetable could help people “see better in the blackout.”

The government made so much noise about carrots that it was news in the United States and elsewhere. “Lord Woolton, who is trying to wean the British away from cabbage and brussels sprouts, is plugging carrots,” Raymond Daniell, the New York Times’ London bureau chief wrote in an article about blackout survival techniques. “To hear him talk, they contain enough Vitamin A to make moles see in a coal mine.” That Lord Woolton, the peer heading the Ministry of Food, was known to say, “A carrot a day keeps the blackout at bay.”

Portraying carrots as a night vision-enhancing superfood had another benefit—hiding a secretive English radar technology from the Nazis. To stymie Germany’s night-time bombing raids, the Royal Air Force pioneered the Airborne Interception (AI) radar. Britain already had a land-based system of radar towers along the coast. But the AI radar could be mounted to planes and detect German bombers from the air.

To keep the new tech secret, “night fighters” were publicized as having night vision spectacular enough to spot enemy planes in the dark. Officials began telling reporters this ability was supplemented by a carrot-rich diet.

The most successful night fighter became a sensation. The media lauded John “Cat’s Eyes” Cunningham for his ability to spot Luftwaffe bombers at night. But even his cool nickname was misdirection. While the Air Ministry claimed a diet of carrots was responsible for his spectacular shooting prowess, his accuracy was in a large part due to the AI Mark IV.

Tales of Cunningham’s prowess spread to the United States. On December 7, 1941, a Washington Post article gushed about Cunningham, describing him as “[25] years old, blond, [and] handsome enough to make a couple of movie stars worry about their jobs.” The article added that Cunningham’s diet would motivate parents in Great Britain and “across the Atlantic” to feed their children carrots. (Cunningham himself disliked the “Cat’s Eye” nickname and the limelight.)

The Ministry of Food’s propaganda reached the United States, too. As Americans prepared for potential blackouts, they looked to Great Britain for inspiration. “England grows a lot of carrots, and it’s on them that she largely relies to prevent her people from bumping into lampposts, automobiles, and each other,” the New York Times reported on January 25, 1942. The Times also included a Ministry of Food recipe for carrot and potato pancakes as part of a vitamin-A rich “Diet for Blackouts.”

Meanwhile, England developed “Dr. Carrot,” a cheerful cartoon carrot with a top hat and a medicine bag emblazoned with “VIT-A.” Lord Woolton even roped Walt Disney into the carrot-lauding game. When Woolton sent Disney a telegram asking for more carroty mascots, Disney immediately had one of his artists whip up the Carrot Family: Carroty George, Pop Carrot, and Clara Carrot. Printed on newspaper inserts and event posters, the Carrot Family was “food propaganda,” often accompanied by recipes.

The Germans were probably never fooled by the carrot trick, and the ruse was rendered moot when Germany developed its own AI system. But for years, Britons and Americans were bombarded with carrot propaganda and publicity surrounding British flying aces and their carrot-filled diets. Cunningham and Carroty George may be hazy memories, but their message endures. Though born of wartime necessity, the concept of carrots’ eye-strengthening qualities has grown deep roots.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook