At ‘Soda Springs’ in the Philippines, the Seafloor Bubbles Like Champagne

The bubbles are mostly carbon dioxide, and gurgle up from the ground in streamers or curtains.

If you’ve ever wondered what it would be like to float in seltzer water or swim in a glass of champagne, you should go diving with Bayani Cardenas.

Cardenas, a hydrologist at the University of Texas at Austin’s Jackson School of Geosciences, recently dove in Secret Bay, off the southeastern tip of Mabini in the Philippine province of Batangas. A local diver had tipped Cardenas off that far beneath the surface of the water, spectacular quantities of bubbles gurgled up from the bottom.

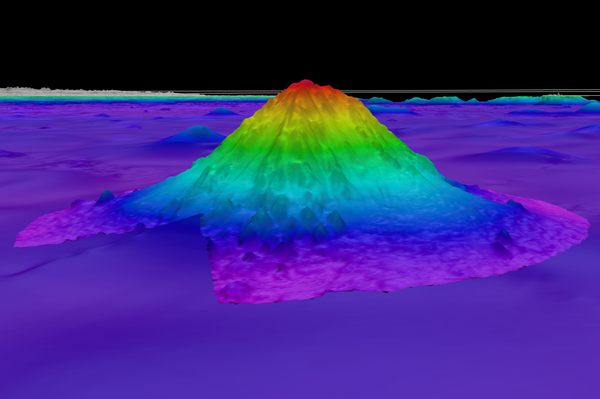

Some bubbles came a few at a time, in little hiccups, while others twirled like streamers. “At first, you see maybe a bubble spring every 50 feet or something, and then 150 feet down, you see a whole curtain from a distance,” Cardenas says. In some patches, he adds, the bubbles were “just gushing.” The researchers went down nearly 200 feet.

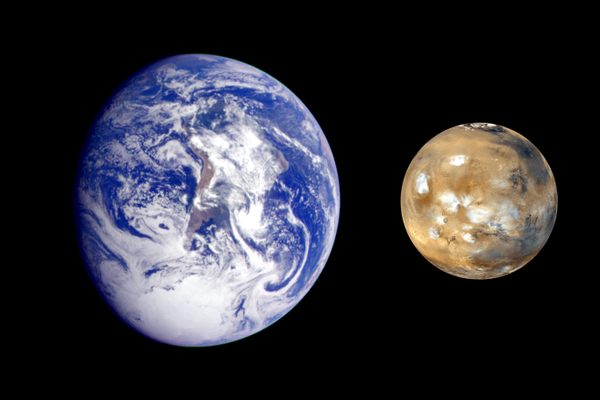

This area sits along the Verde Island Passage, a watery corridor between the islands of Luzon and Mindoro known to harbor immense marine biodiversity. The bottom of Secret Bay was so effervescent that the researchers dubbed it Soda Springs—and though Cardenas and his collaborators were there to investigate groundwater discharging into the ocean, they figured that the bubbles warranted a closer look, too. Armed with carbon dioxide sensors, they swam through the bubbles to measure the concentration of the gas.

It wasn’t always easy to stay focused on the scientific tasks: The bubbles were uncomfortably itchy when they hit the exposed skin on divers’ hands and faces, Cardenas says, and it would be easy to forget to monitor their oxygen tanks while distracted by the “surreal” visuals. It helped to try to mute the sensory stimuli, Cardenas says, because “you want to make sure you’re not too excited.” Everything, from flailing your arms to scratching your nose, is more arduous in water than it is in air, and Cardenas and his dive partners rehearsed their game plan over coffee and breakfast, plotting out how they’d pass instruments back and forth and then stash them.

In some portions of Soda Springs, the divers measured carbon dioxide concentrations of up to 95,000 parts per million, Cardenas and 10 collaborators report in a new paper in Geophysical Research Letters. That’s more than 200 times the concentration found in the atmosphere, which is around 412 parts per million, according to a 2019 report from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

The researchers also got to the bottom of the all-natural bubble machine: They report that it’s the product of gas seeping out of seafloor vents. The area is a hotbed of volcanic activity; the Taal volcano recently erupted just 23 miles away. “Where these vents are, there are probably faults underneath there that we’re not seeing, that are all covered up by sediment,” Cardenas says.

The next question, Cardenas says, is how these outpourings of carbon dioxide affect the coral reefs and other life nearby. Although the gas becomes less concentrated as it rises, the team detected elevated levels of carbon dioxide along portions of the shoreline, along with increased acidity. Researchers who choose to dive into that research question will also get to frolic in all the bubbles they could ever want.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook