Meet California’s Nerds of Neon

These photo-taking, model-making obsessives are documenting the state’s vintage signs before they vanish.

Chris Raley will never make a “Welcome to Las Vegas” sign, so stop asking. “There are entire gift shops in Vegas full of ’em,” he says. And Raley isn’t interested in doing what everyone else is doing.

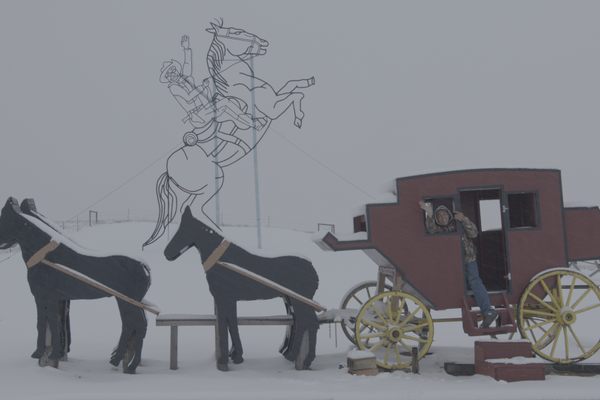

His workshop—a spare room in his tan, two-story Fresno home that’s painted yellow and filled with thrift-store finds—attests to this fact. Standing atop a table are several unique acrylic models of commercial signs, most less than 18 inches tall, that you won’t find in Vegas gift shops—signs advertising the Safari Inn, Western Appliance, the Sun N’ Sand Motel, and more.

Raley, an affable, soft-spoken 48-year-old who favors a T-shirt and jeans, has been building these miniature signs for the past two years. He belongs to a loose fraternity of Californians who are obsessed with vintage signage. Sometimes referred to online as #signhunters or #signspotters, these sign geeks congregate around photo-sharing sites like Instagram (and in the earlier days of the Internet, Flickr) and bond over their love of the big, bold, over-the-top signs of the mid-20th century—the glory days of roadside advertising.

Some of the signs they document are more famous than others—Roy’s Motel, for instance, and the Milk Farm Restaurant, and Circus Liquor (yes, that Circus Liquor). But they’re all quintessentially Californian. Thanks to the state’s world-famous car culture, placards like these once dotted main drags from San Diego to Sacramento.

But that was then. These days there aren’t many neon beacons beckoning to drivers on California thoroughfares. As the state’s population swells, and its once-funky places gentrify, a small community of signhunters (the sign geeks who visit vintage placards in person) are racing to document the signs they love—taking and sharing photos, rendering skillful sketches, making miniature scale models—before they get knocked down to make way for condos and Walmarts.

Growing up in a town about 40 miles north of Fresno, Raley drove past the Astro Motel sign countless times. He didn’t think much of it back then. But in 2015, a realignment of State Highway 99—to accommodate California’s long-time-coming high-speed rail project—put the sign in harm’s way.

“I knew it was getting close [to being removed],” he says. “ And one day I drove down the freeway, and it was gone … I didn’t get choked up, but I came real close.”

For Raley, a stay-at-home dad, that was the turning point. Something changed. The Astro Motel sign became his muse. But how best to memorialize it?

First he tried painting a picture. But “it came out horribly,” he says, pointing to the finished painting—which isn’t as bad as he says—in his sawdust-sprinkled garage (the leftover sawdust is from a previous woodworking hobby). So Raley moved on to making models. Which made sense: A former Air Force mechanic, he’s more comfortable following blueprints than blind intuition. His first work was a three-inch wooden model of the Astro Motel sign, based on photographs and his own memory.

He wasn’t happy with how that one came out. But a little while later he made a miniature drive-in marquee, as a gift for a movie-loving friend. Before long Raley was regularly creating models of his favorite signs—a way to memorialize past ones he’s loved and honor those still standing.

Raley starts a new project by consulting photographs—usually drawn from the vast image libraries that other signhunters have posted on photo-sharing sites—and using them to estimate the sign’s dimensions. Then he plugs the dimensions for some basic shapes into his 3D printer. (Until this year, most of Raley’s signs were made of wood. But since he invested in the 3D printer, his works are usually laser-cut acrylic.)

Next he uses a font-finder program to replicate outdated fonts, which he traces onto vinyl or directly onto the sign-to-be. Then he paints or applies vinyl to the shapes, to match the original colors. Last comes the assembly process. Some signs, like Circus Liquor, can be replicated mostly in one piece. But for signs like Deano’s Motel, Raley needs to attach multiple parts together—sometimes motors or lights too. For those he uses wood glue, epoxy, or magnets to keep everything in place.

The result is a veritable Santa’s Village of vintage signs, no more than two feet tall, that live in his workshop at home (or are occasionally available for purchase at the Valley Relics Museum in Van Nuys). Whether still standing or long gone in real life, these signs are now preserved for posterity as miniature models.

Raley and the other signhunters tend to focus on signs from the middle of the 20th century. But the history of commercial signage in the U.S. goes back to at least the 18th century. Some of the earliest signs in America were those on taverns, like the ones that still hang outside pubs in Ireland and the U.K. Proprietors named their establishments after well-known objects or animals, and the sign they hung outside used a combination of words and images to let passersby, of all literacy levels, know they were in the right place.

When electricity began illuminating the U.S., around the turn of the 20th century, signs started lighting up too—first with incandescent bulbs, and later with neon. In the years after World War II, signs were the primary form of advertising for businesses in the United States.

“If you didn’t have a sign, you didn’t exist,” says Heather David, a historian of midcentury architecture and founding member of the San Jose Signs Project, a group that advocates for the protection and preservation of vintage signage and architecture in the city.

By the mid-1960s, California’s highways—and the rest of the nation’s—were fairly screaming with advertisements. But that would soon change. In 1965, Lady Bird Johnson fostered the Highway Beautification Act, which Congress soon passed. The result: Hundreds of roadside signs were torn down, and laws limiting the size and number of signs that could go up were strictly enforced. In the 1970s, environmental concerns led to even more restrictions on where outdoor advertising could and couldn’t go.

As prominent signs became more rare, early signhunters like Jim Heimann, an editor at Taschen and the author of California Crazy, set out to document them. “Much of my original inspiration came from the discovery of the [Farm Security Administration] photographers in the 1930s,” he says. Signage and billboards often served as the backdrop to their work—an aesthetic choice that informed Heimann’s documentation of the signage he found in Southern California.

Later that decade and into the ’80s, as good-old-days nostalgia for the postwar period became fashionable, photographers like John Margolies published coffee-table books and prominent magazine spreads showing America’s wacky, wonderful roadside advertising. Most signhunters today still use photography to document the vanishing treasures they find. But some, like Raley, use other media.

San Jose artist Suhita Shirodkar is another one. A native of Bombay, she moved to San Jose in 2005, and immediately found herself captivated by the city’s extant signage. To document it, she began carrying a sketch pad with her everywhere she went.

“[These signs] seem like they shouldn’t have remained part of the landscape,” she says. “Many of them don’t … match what’s around them. [They] stand randomly in the middle of a parking lot that doesn’t have any vestige of the store that they talk about.”

In 2017, when Shirodkar began posting the sketches she was making of pre-tech Silicon Valley, including its signage, the signhunter community caught wind of her work. “It’s been immensely popular,” she says of her sketches. “And it’s been connecting me to people I don’t come across in my everyday life.”

San Jose is a particular mecca for signhunters. After World War II, it flourished as an airy alternative to cramped, vertical San Francisco. “I don’t remember the exact numbers, but I think San Jose quintupled,” says David. “From ’45 to ’65, we just exploded,” and sign-flecked shopping boulevards sprung up to serve the growing population.

Ironically, the same rapid development that birthed these signs then is contributing to their demise now. As tech workers flock to the Bay Area today for jobs at Google and Apple, making San Francisco prohibitively expensive, San Jose has scrambled to provide housing for them. That’s meant displacing longtime residents, beloved restaurants, and—yes—vintage signs in the process. “At least a third of the book is gone,” says Shirodkar, referring to the San Jose signs she sketched for a book published in 2018.

As rents rise and businesses change hands, signs advertising places like Mel Cotton’s Sporting Goods, the Bold Knight restaurant, and Cambrian Bowl—quirky billboards that have long served as landmarks and cultural touchstones for locals—have come down. Their removal is a blow to many residents, who are watching their hometowns change quickly and drastically.

In 2018, the sign advertising San Jose’s Orchard Supply Hardware—a big arrow that beckoned drivers crossing the San Carlos Street overpass—was taken down after the company folded. (Soon thereafter, its historic sign, which dates to the early 1950s, was stolen. Earlier this year it was recovered.) “Just think about … how many people have gone to Orchard Supply Hardware,” says David. “It’s a company that was founded in San Jose. It’s us.”

But it’s not just them. Fresno, too, is plagued by housing woes, as a construction boom there is imperiling the city’s vintage signs. Much of the rest of California—including Los Angeles and the suburbs that surround it—is in the same boat.

Can work like Raley’s and Shirodkar’s act as a visual bulwark against unchecked corporate expansion? Can it help keep alive the memory of midcentury mom-and-pop individuality? Raley sure hopes so.

“The Astro Motel sign—it no longer exists, except for in this room,” he says. “And so in a way, in a very small way, it’s been brought back to life.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook