British Spy Agency Tried to Stop a Massive Harry Potter Leak

“We don’t comment on our defense against the dark arts,” an agency spokesperson said.

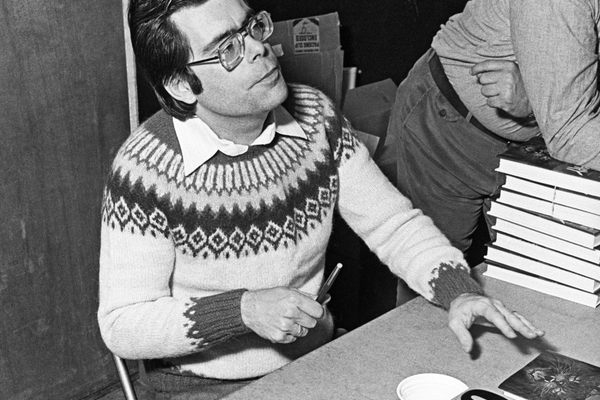

Fans waiting to buy Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince. (Photo: Raul654/CC BY-SA 3.0)

The year 2005 was a different time. A lot of people were wearing trucker hats, for example, and, until April 2005, we didn’t have YouTube. Weirder still were the millions of people across the globe who read collections of words printed on hundreds of pages of paper, which were then bound, marketed, and sold in places called bookstores.

It was also a time when the internet’s capacity to spoil every good plot twist was just in its infancy. The biggest spoiler in 2005, maybe the biggest of the decade, had to do with the new Harry Potter book, which would go on to sell over 65 million copies. Which major character was going to die in Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, the series’ sixth installment?

J.K. Rowling had hinted that someone would, but the fans really couldn’t wait, and Rowling said that some were even searching through her garbage for clues. (I think I’m safe in revealing 11 years after the fact that it was Dumbledore. Dumbledore died.)

Yet, it was in this culture of general hysteria that the Government Communications Headquarters, the British surveillance agency, apparently intervened to try and help Rowling’s publisher keep the secret.

“We fortunately had many allies,” Nigel Newton, founder of the book’s publisher Bloomsbury, recently told ABC radio in Australia. “GCHQ rang me up and said, ‘We’ve detected an early copy of this book on the internet’. I got them to read a page to our editor and she said, ‘No, that’s a fake’. We also had judges and the police on our side.”

Should governmental spy agencies be in the business of helping for-profit companies keep their own secrets and thus sell more books? It’s a complicated question. Back then, it probably felt like life or death.

“We don’t comment on our defense against the dark arts,” an agency spokesperson told The Times.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook