An Outlaw’s Skin Was Made Into Shoes

Should they be on display?

The Carbon County Museum in Rawlins, Wyoming, is home to a number of terrific exhibits that recall the area’s roots in the American West. They include a look back at the Union Pacific Railroad’s impact on the region, as well as a tribute to Thomas Edison’s 1878 visit to Wyoming Territory. But there is one display that tends to garner the most attention from visitors: a pair of shoes made out of the skin of the late-1800s outlaw, Big Nose George.

“We’ve moved the shoes into a corner of our facility, and set up a partial wall, so that if you have an aversion to seeing human remains, you can avoid it,” says the museum’s director, Kelly Bohanan. “What we often find is that that is what [people] came to see, and they run the beaten path right to it.”

While anything that attracts a crowd to a museum could be considered a good thing, the enthusiasm these gruesome shoes continue to inspire is complicated to say the least. Their special place in the Carbon County Museum’s collection raises the question: how should we deal with the remains of outlaws?

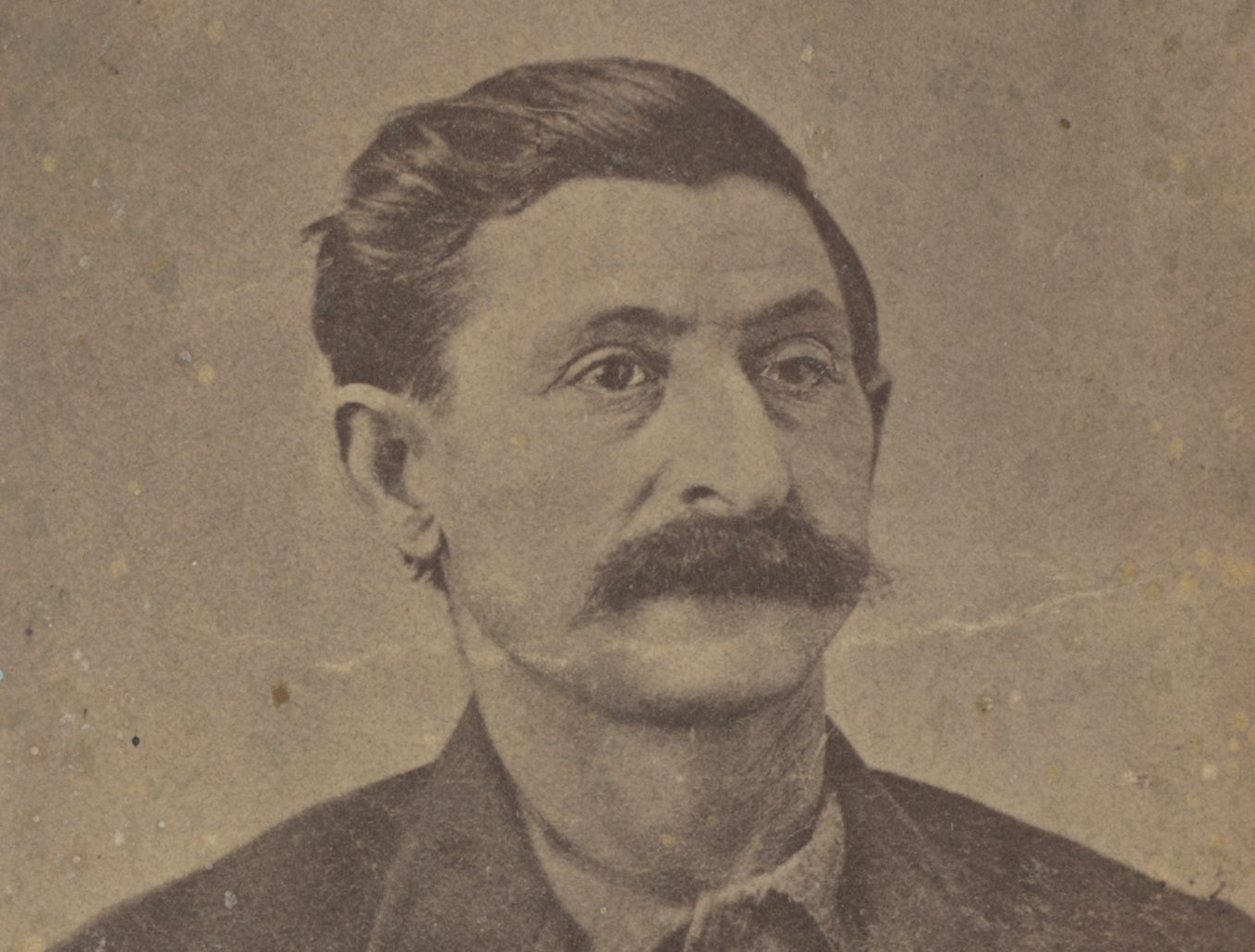

“Big Nose” George Parrott was a bandit, murderer, and horse thief whose crimes came to an end in 1881. Parrott and his gang killed a pair of lawmen in Wyoming after a failed train robbery, after which he went on the run for two years. Despite the bounty on Parrott’s head, according to an account in the book Legendary Locals of Rawlins, at one point he began drunkenly bragging about having killed the Wyoming lawmen, which eventually led to his capture in 1880.

Law enforcement officials returned Parrott to Wyoming shortly after his capture, where a mob was waiting for him. “When he arrived by train, there was a lynch mob that had already formed, and they were going to just lynch him right off the train,” says Bohanan. “There must have been something fairly charismatic about him, because he convinced that lynch mob to allow him to go to trial.”

The trial led to a guilty verdict, and Parrott was sentenced to be hanged. But ever the outlaw, he wasn’t about to take his verdict lying down. While in jail in Rawlins, Parrott managed to remove his shackles and beat up a jailer in an attempt at escape. He was stopped by the jailer’s wife, who held Parrott at gunpoint. Word of the attempted escape quickly spread throughout the town and another mob formed. They burst into the jail and dragged Parrott into the street, holding the poor jailer, who despite the attack was still charged with protecting Parrott, at gunpoint.

The mob strung Parrott up on a telegraph pole, but the attempted hanging failed and Parrott fell to the ground. During a second attempt, the too-short rope failed to break Parrott’s neck, leaving him to strangle on the line. This time he was able to free his hands and shimmy up the pole, out of reach of the mob. “Witnesses say that he was begging for someone to shoot him,” says Bohanan. Eventually, Parrott fell off the pole and was again imprecisely strung up, violently strangling to death. By the time he was brought down, and as can be seen on his death mask, the rope had rubbed his ears clean off during the clumsy execution.

The outlaw’s body was brought to the local coroner’s office, but it didn’t stay there for long. Parrott’s corpse was taken, under cover of darkness, by the physicians John Osborne and Thomas Maghee, who ostensibly wanted to experiment on Parrott’s remains to try and find the source of his criminality. Osborne kept Parrott’s body in a whiskey barrel in an office for around a year while the two men conducted experiments. At some point, Osborne sent parts of the cadaver to a tannery, and commissioned the pair of shoes, as well as a medical bag and a coin purse, made out of Parrott’s skin. The top of Parrott’s skull, which had been lopped off to expose his brain, was given to Maghee’s assistant, Lillian Heath.

According to Bohanan, Osborne’s true motive behind creating the ghoulish accessories remains unknown. “The medical profession at the time looked at human remains as nothing more than something to be learned from,” she says. “I’ve been told that it wasn’t an uncommon practice, but I have trouble believing that.”

Once the doctors were finished with Parrott, they buried the barrel containing what was left of his remains, and Parrott’s story began to fade into legend. The barrel was finally uncovered in 1950 by construction workers. Heath, who went on to become Wyoming’s first female physician, reportedly kept the skullcap throughout her life, and is said to have used it as both an ashtray and a doorstop. It is now held in the collection of an Iowa railroad museum. The lower half of the skull, as well as the shoes, are in the Carbon County Museum.

The whereabouts of the medical bag are today unknown, while the coin purse, which was also once part of the Carbon County collection, was at some point misplaced. “The coin purse we know we had in our collection. We know this because we had a gentleman who worked in the museum from the time he was around 11 years old until the time he died in his 70s, and he knew we had the coin purse,” says Bohanan. At the time, the cataloging system wasn’t as good as it was today, she says, and it was maintained by volunteers, which didn’t bode well for the small pouch. “Apparently these little old ladies didn’t want to deal with the coin purse, because it was made out of his scrotum.”

Today, Parrott’s skull is not on display, but the shoes remain a complicated artifact, at once a major attraction as well as a morbid relic that raises questions about the proper handling of human remains. Bohanan says she tries to remain understanding of both sides of the issue. “He was a criminal, and he had a hand in the deaths of two law enforcement officials. I think that today, the sentiment is still some of the Wild West sentiment, that they were criminals and that they don’t deserve the dignity, or for anything good to come for the rest of their lives, and who cares about their afterlife,” she says. “Some people in the museum say, ‘They’re shoes. They were made to look like shoes, they were worn as shoes, they are shoes.’ The flip side of that argument is, tell that to his mother.” Bohanan says one of the museum’s registrars once quit when the shoes and skull were temporarily taken off display in deference to some sensitive visitors.

Despite the conflicting views on the shoes, they aren’t going anywhere any time soon. “I can’t imagine a time in our county when those shoes will come off of display,” says Bohanan. But she also acknowledges that times are always changing. “I’m sure that at some point, someone is going to question the need to have them out.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook