Berlin’s Secret Cold War-Era Vineyard

This tiny, hidden vineyard planted at the birthplace of the first computer produces only 350 bottles of wine each year.

Mention the word “vineyard” and most people will think of rolling green hillsides or sweeping valley views. Yet few of them would expect to find one right in the heart of one of Berlin’s hippest districts, Kreuzberg. A true relic from the Cold War era, this tiny urban vineyard is one of the German capital’s best kept secrets. The vineyard covers a tenth of a hectare and it produces about 350 bottles of wine yearly, called Kreuz-Neroberger. Grapes for the rare wine are grown at the very birthplace of the first programmable computer in the world, which only adds to its mystique. It is notoriously hard to obtain.

Over the last couple of years the secret vineyard has been overseen by Daniel Mayer, a jolly 44-year master oenologist and winemaker. A Berlin native, Mayer worked for many years as a wine buyer before taking control over the small urban vineyard, and pulling the German capital’s little-known but glorious winemaking past into the 21st century.

“I took over the Kreuzberg vineyard in 2010 when a friend of mine asked me if I would be interested in it,” says Mayer. He wears a T-shirt with an inscription in Latin saying Vinea in Monte Crucis / MCDXXXV Vindemia MMXV (The Vineyard in Kreuzberg, 1435-2015). The text, although ironic, reflects an important historical truth: vines has been grown in this part of Berlin for centuries, with the first vineyard planted on the hills of Kreuzberg more than 580 years ago.

The Kreuzberg vineyard that Mayer is taking care of is not nearly that old. It was planted in 1968, in the midst of the Cold War era, when the district’s twin city of Wiesbaden donated five Riesling vines. Between 1971 and 1973, Bergstraße county, a wine region in the state of Hesse, gifted another 75 vines. In 1975 the town of Ingelheim am Rhein donated 20 Blauer Spätburgunder vines. Today the Kreuzberg vineyard contains 350 vines in total, all of them gifts.

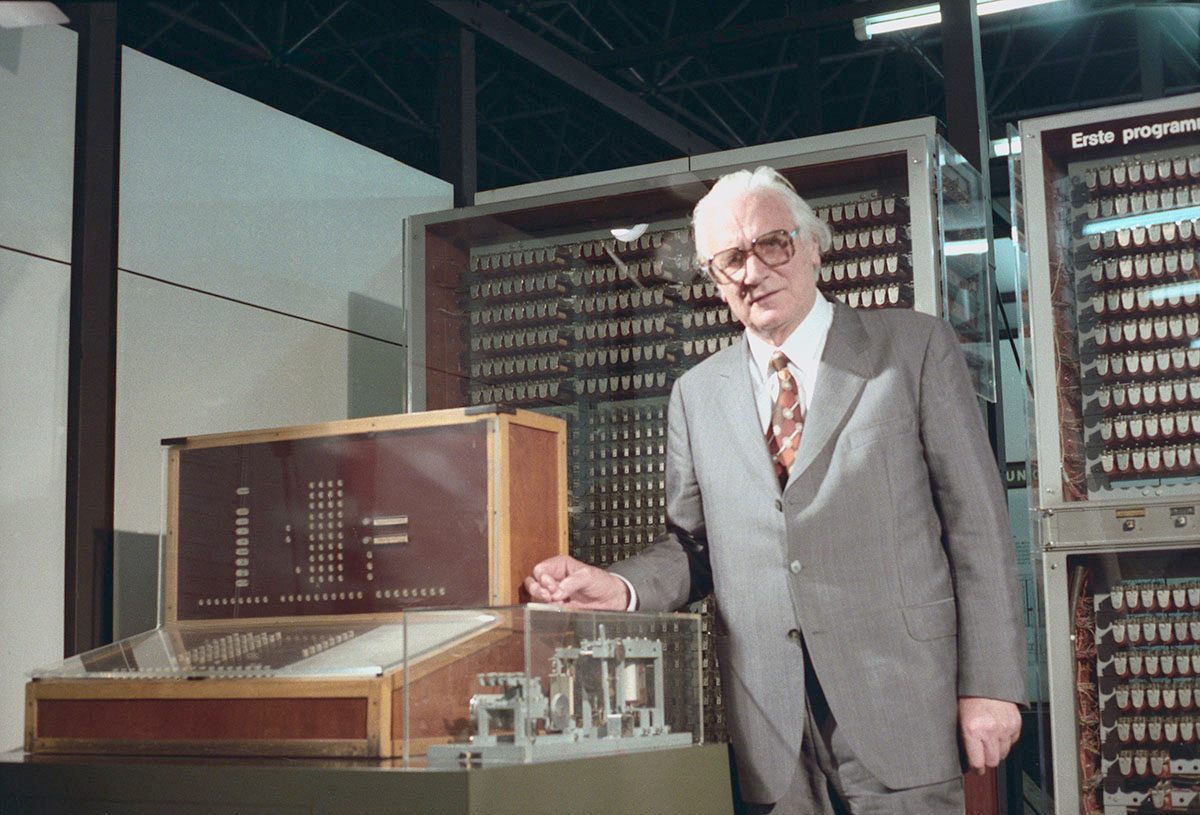

Like many of the best vineyards, the one in Kreuzberg is planted on a slope, not far from the charming 19th-century idyll of Viktoriapark. But what’s even more unique about the vineyard’s location is that it grows at the very birthplace of Z3—the world’s first working programmable, fully automatic digital computer, designed by German engineer Konrad Zuse. Thanks to this machine and its predecessors, Zuse (1910-1995) is often regarded as the inventor of the computer. Unfortunately the machine and its blueprints were destroyed during World War II, in a bombing of Berlin in December of 1943. So was the laboratory of Zuse, as well as the whole block around it, which opened a wide gap in the otherwise densely built urban area.

“A couple of years ago one of the mayoral candidates of Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg borough came with a guy from the museum and an architect and said that according to some plans, the cellar of Zuse’s house has never been filled up with earth after the war, so there might still be a computer in there,” laughs Mayer.

The Romans first introduced viticulture to the southernmost area of present-day Germany about 2,000 years ago, and by the early Middle Ages, it was usually being made in monasteries. In fact, Berlin’s Kreuzberg district has older winemaking traditions than more popular regions such as California, Australia and South Africa. But with the rapid expansion of Berlin in the 19th century, many of the vineyards were pulled out and replaced by residential buildings. Yet Berlin and the surrounding Brandenburg area abound with names that are deeply rooted in its glorious winemaking past, like Weinmeisterstraße (Winemaster street), Weinbrennerweg (Wine distiller way), and Weinbergpark (Vineyard park), to name but a few.

“Wine was a big thing here. And sometimes it was cheaper than beer which helped its popularity. The city produced so much of it that they even exported some to Scandinavia and the Baltic republics,” explains Mayer. “But then all this came to an end. One of the reasons was globalization, as it was much easier to get cheaper and better wines via the railway from other parts of Europe.”

The Kreuzberg vineyard was a project started by then-Mayor of West Berlin, Willy Brandt, in 1966. Its goal was to seal the city partnership between Kreuzberg and Wiesbaden. It was a strong political statement, saying that West Berlin, which existed between 1949 and 1990 as a political enclave surrounded by East Germany, had not been forgotten by West Germany. The annual harvest was initially modest, with 11 bottles in 1970 and only seven bottles in 1971. The choice of grapes was political, too, but not necessarily the best one for Berlin’s climate.

“Riesling takes a very long time to mature, but back in the 1960s they had different, political reasons. The Riesling vines came from Kreuzberg’s sister city of Wiesbaden, the capital of federal state of Hesse, which is in the Rhine district famous for its white wines,” explains Mayer.

Due to Berlin’s northern continental climate, the grapes planted at that time couldn’t ripen well and the wine was thin and acidic. Or as they used to say, “Brandenburg’s wine goes down one’s throat like a saw.” The wine made in Kreuzberg wasn’t an exception.

But in recent years its quality has improved, thanks to the rising temperature of the city. Berlin’s urban area has a unique microclimate: heat is stored by the city’s buildings and pavement, and temperatures inside the city can be 4°C (7 °F) higher than in its surrounding areas. According to Mayer, sometimes as little as half a degree makes a big difference on the grapes’ ripeness.

Two grape varieties are grown—Riesling, the most widely planted of German grapes, and Spätburgunder or “Late Burgundian”, as Pinot Noir is known in Germany. The vines are lovingly taken care of all year long by Daniel Mayer and volunteers who help with all the work, including pruning and harvesting. Each one of the 350 vines produces roughly one 0.375 liter bottle of wine which is 100 percent organic, as Mayer uses only copper and sulfur fungicides which are more or less harmless.

“The vineyard is so small that we do everything by hand. We spend about one hour of work per bottle of wine. Or 350 hours yearly in total. But this is only to produce the grapes. Then we have to bring them to the sister cities which turn them into wine and this adds to the cost of production,” explains Mayer.

The Kreuz-Neroberger wine is still bottled in the same narrow, oblong, cylindrical bottles made of brown glass that were used for first time in 1970, when the first vintage of it was pressed. But what about the wine itself?

“It’s uncomplicated table wine with floral notes. It has hints of peaches and light citrus notes, a good balance and a medium-long finish,” explains Mayer.

The Kreuz-Neroberger wine is famously hard to obtain. You won’t find it in the wine lists of the fancy restaurants and you can’t buy it in the shops, not even in the specialized ones. However, a donation of 10 Euros (about $10.60) to the district office of Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg will get you a standard 0,375 liter bottle.

The other way of scoring a bottle is a bit trickier: if you reach the ripe old age of 100 years, then you’ll get a bottle of it for your birthday.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook