Belize’s Maya Drained Their Swamps to Make Farmland

Their wide-reaching wetland agriculture helped support the civilization.

In recent years, talk of “draining the swamp” has gotten awful popular in the United States. Swamps and wetlands are a lot of things—critical wildlife habitat, buffers against storms, and natural filtration systems, as well as places to hide, barriers to agriculture and development, and refuges for disease-spreading mosquitoes. In short, our modern relationship with wetlands can be complicated. The ancient Maya of Central America were pretty clear about their wetlands: They were a resource, a place to cultivate crops for nearly 1,000 years through a system of wetland agriculture. A new paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences is showing just how complex and massive Maya wetland agriculture was.

“When Europeans came to America they had a very negative view of wetlands,” says Timothy Beach, a geoarchaeologist at the University of Texas at Austin and coauthor of the study, “but to most Americans, they were like our refrigerators today. They were filled with all kinds of goods.”

The fact that the Maya employed irrigation agriculture has been known for some time. Many of their ruins had been systematically explored and documented—going back to the 19th century—but uncovering the extent of their elaborate landscape engineering has taken a little more time. As more and more major Maya population centers were uncovered, there was great speculation about how many people they held, and how those populations maintained a steady supply of maize, avocado, squash, and other foods. As far back as 1981, it was reported that their agricultural systems were large and complex—suggesting big populations throughout the Maya world.

But there has been skepticism about the scale of it all, and some scholars even doubted that Maya populations were all that big. Estimates of the size of the civilization, its population, and its footprint have varied over the years, and it seems like every time scholars look, the picture gets more complex. The question hinges both on the extent of Maya fields and how efficient their agricultural practices were. This latest research suggests that what we know of Maya wetland agriculture could just be the tip of the iceberg.

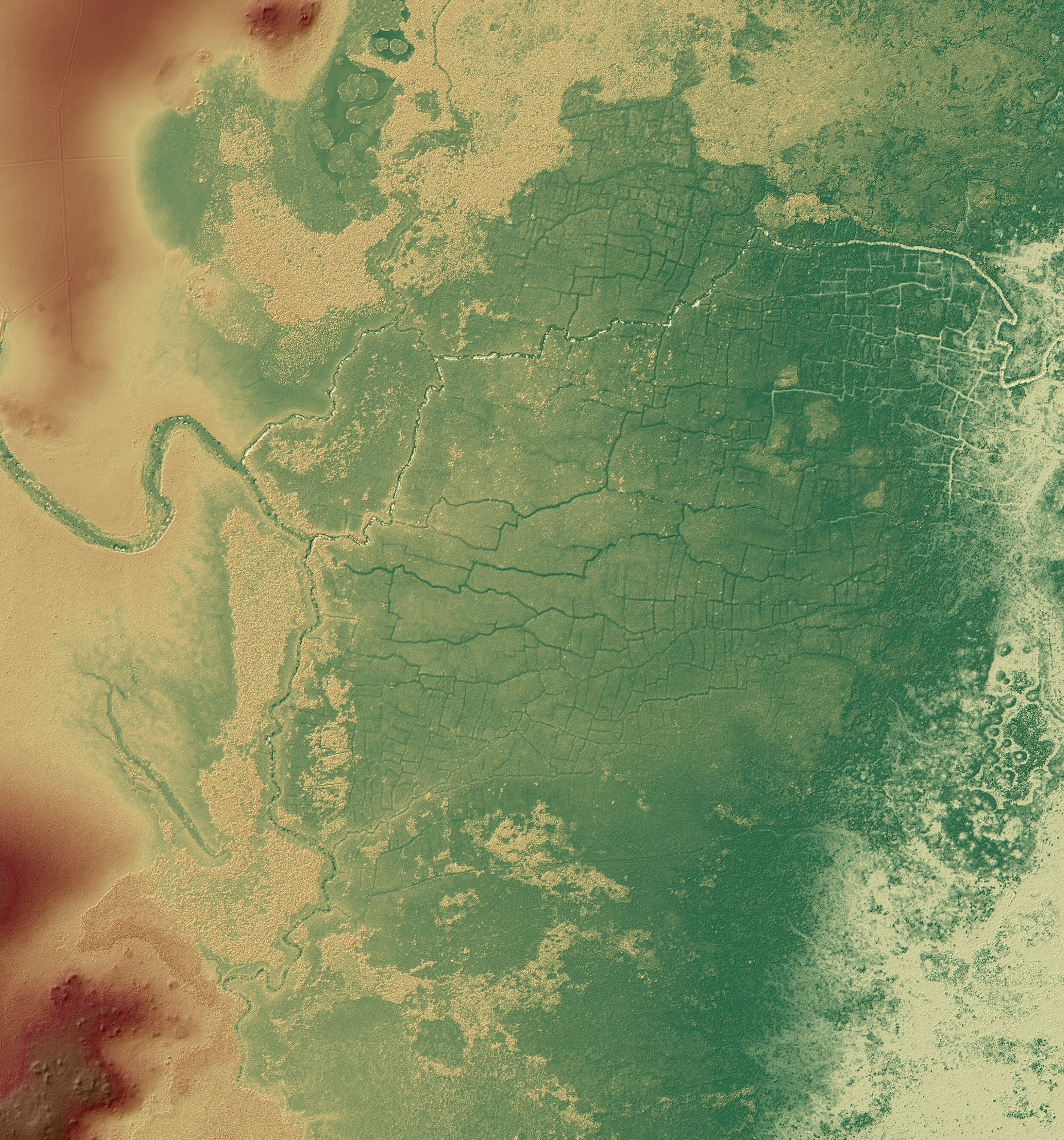

Beach’s team focused its efforts on the Rio Bravo watershed in northwestern Belize to get a sense of Maya agricultural sprawl. They conducted excavations in fields and canals, looked at pollen residue in the soil layers to learn what crops were grown, and applied radiocarbon dating. Perhaps the most helpful technology in their toolkit was lidar, aerial radar that provides a clear look at what is hidden under the forest canopy that now covers the entire area.

The lidar showed vast stretches of Maya canal and field systems throughout the area the researchers studied. One of the four complexes examined in the paper, the Birds of Paradise wetland complex, was found to be five times larger than previously known.

“It did surprise us, to tell you the truth,” Beach says. “I had an inkling the fields were larger, but I had no idea we’d find new areas up the valley.”

“With the lidar it’s becoming clear that we need to swing back to the viewpoints of 30 to 40 years ago,” adds Stephen Houston, an archaeologist at Brown University, when it was thought that Maya populations were, in a word, huge. “Now we’re getting the full body blow of how extensive these systems were. You might say this has a ripple effect outward on the ancient Maya, and tells us there were a ton of people.”

The Maya had cleared densely forested areas for the canals and fields by cutting down and burning much of the swamp forest, beginning 1,300 years ago. Canals were then dug in a pattern that resembles rectangular veins, to drain and distribute water through the fields.

“We know where they did it and we know how they did it,” he says. The next step will be developing a better understanding of the hydrology of the system. “We’re still trying to figure that part out,” he adds.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook