How a 1960s Cookbook Became a Window Into the Secret Lives of Ballet Icons

The out-of-print book became a ballerina’s second act.

“Soufflés fall and so do dancers, and both survive: The main thing is to forget it,” wrote the late Tanaquil “Tanny” Le Clercq, a New York City Ballet principal dancer, in The Ballet Cook Book. In this passage from her obscure work, Le Clercq detailed a mortifying spill she took during a performance at Washington D.C.’s Constitution Hall. “Time heals all wounds: this happens to be true,” she continued.

As a resilient and sharp-witted ballerina-turned-writer, Le Clercq knew a thing or two about brushing yourself off and pressing on. Discovered by legendary choreographer George Balanchine (whom she later married), Le Clercq began performing professionally while she was still still a student. She joined the Russian émigré’s troupe, now known as New York City Ballet, taking on roles in Afternoon of a Faun, La Valse, and other beloved ballets still performed today.

At one notable March of Dimes charity show, Balanchine played an ominous character, “Polio,” while his pupil played his unfortunate victim. This performance would be a footnote in the ballerina’s biography if it wasn’t for what was to come: At the peak of her career, while touring in Copenhagen, Denmark, Le Clercq abruptly contracted polio. At the age of 27, she could no longer dance, and the disease caused her to use a wheelchair until her death in 2000, from pneumonia.

After rigorous rehabilitation and settling into her new way of being in the world, Le Clerq set out on an ambitious project, the aforementioned Ballet Cook Book. Though she didn’t have formal culinary training, Le Clercq relished her time in the kitchen. In letters to friends, she shared memories of her latest meals and planned menus for her and Balanchine’s elaborate gatherings. With encouragement from Balanchine, she wrote the 424-page book over the course of several years. Released in 1967, the book features chapters by America’s first prima ballerina and Balanchine’s third wife Maria Tallchief, British choreographer Sir Frederick Ashton, confidante and choreographer Jerome Robbins, Russian superstar Rudolf Nureyev, and over 50 other luminaries.

In the book’s dozens of chapters, Le Clercq offers engaging stories through a wry lens about dancers’ palates and quirks. For instance, Balanchine preferred bagged sauerkraut to canned contemporaries. “The cans aren’t fatal, he just prefers the other,” the writer playfully adds. Meanwhile, Jacques d’Amboise, Tanny’s frequent partner, swore by his “Real S.O.S. Stuffing.” It consisted of three layers of breading with sausage, oysters, and more sausage. In his “Shrimp Sneden,” Robbins confessed that he ate the shells and all.

Its pages also reveal the colorful ways dancers approach performance. It details how a post-show ritual for Cuban idol Alicia Alonso included a relaxing cocktail and, two hours later, a steak. Suzanne Farrell, a dancer a generation below Tanny, traveled with a papier-mâché cat with one ear missing as a good luck charm. One of Le Clercq’s contemporaries, Melissa Hayden, once elbowed herself in the solar plexus so hard that she passed out during a dramatic moment in The Duel at London’s Convent Garden, an anecdote that precedes her recipe for stuffed cabbage. The writer describes it as “a knockout of a recipe worthy of a headline.”

Despite The Ballet Cook Book’s triumph in sketching humanity within these larger-than-life characters, ballet is still often perceived as high-brow, boring, and enigmatic by many. The long-standing belief that dancers have unhealthy eating habits doesn’t help, either. But Le Clercq’s book helps demystify these assumptions while simultaneously offering a window into the eclectic lives of dance’s most beloved figures.

Though Le Clercq and Balanchine’s marriage fizzled out only a few years after the book’s release, and it eventually went out of print, its stories have lived on through the writer’s friends, former colleagues, and curious ballet fans. But in recent years, The Ballet Cook Book itself has undergone a resurgence, largely due to the efforts of educator, writer, and food scholar Meryl Rosofsky. She researched the book as a 2016 fellow of The Center for Ballet and the Arts, and currently leads talks and lecture demonstrations on it throughout New York City.

Rosofsky first got wind of The Ballet Cook Book before hosting a dinner for ballet historian Jennifer Homans, who was writing a biography of Balanchine at the time. “I had recently learned from [New York City Ballet principal dancer] Jared Angle that Balanchine loved to cook,” Rosofsky says over email. “This gave me the idea to research his favorite dishes or recipes to make for this dinner.” That evening, the women noshed on Balanchine’s blini with caviar, a flounder with Georgian coriander sauce, kasha with mushrooms, and Gogl-Mogl, a dish that Rosofsky describes as a “Russian custard Balanchine recalled fondly from his childhood.”

Her research into Balanchine’s recipes led her to learning of Le Clercq’s The Ballet Cook Book, too. “To have [discovered] a compendium like this, so witty and varied, was a light-bulb moment,” Rosofsky says. She realized that this “was a very important document—not any old cookbook off the shelf.”

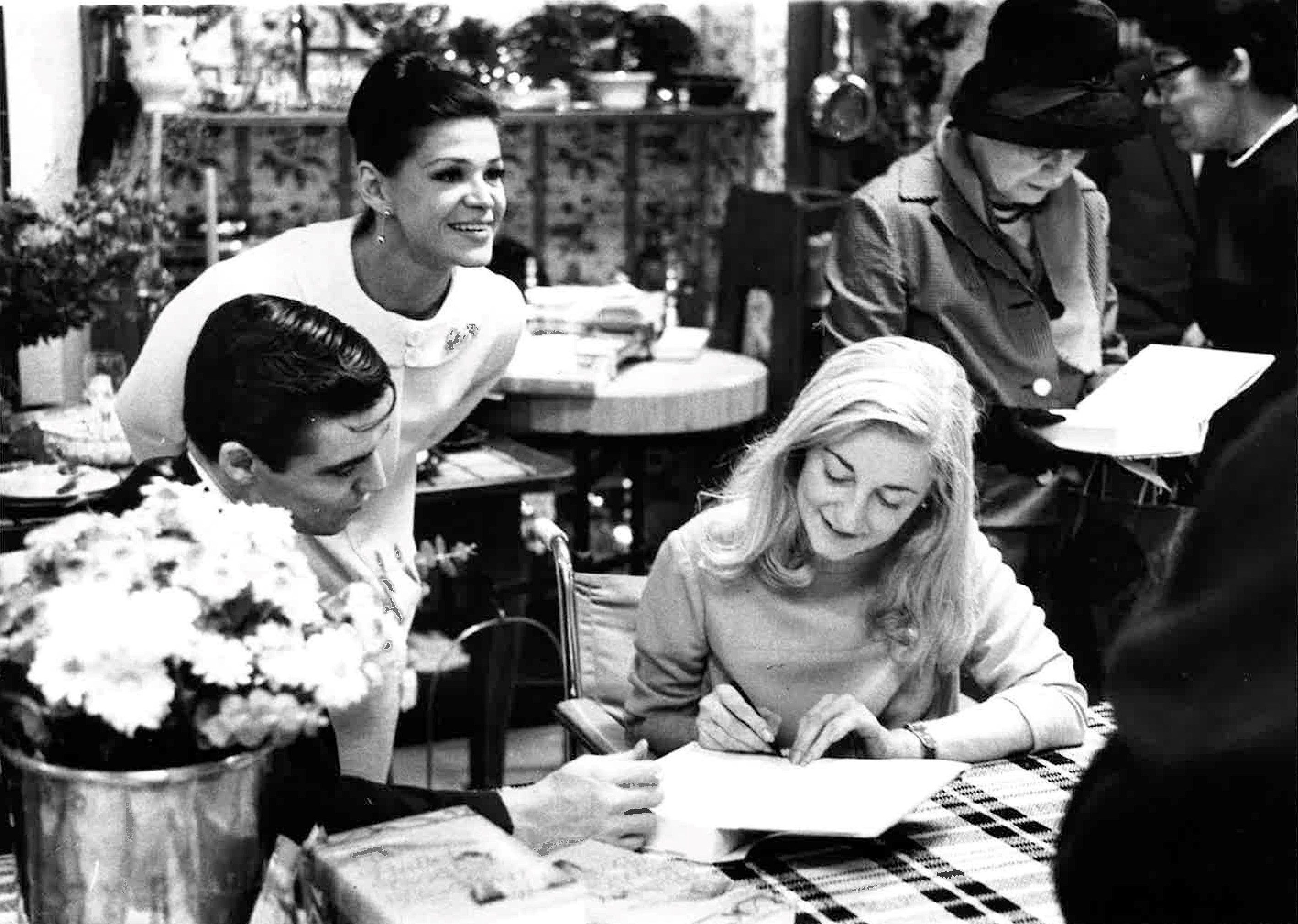

The scholar also happened upon the 2012-2013 The Ballet Cook Book dinner series, led by arts and culture writer Ryan Wenzel and baking enthusiast Susan LaRosa. The six-part series took place in LaRosa’s Brooklyn home, with each event centering on one dancer’s chapter from The Ballet Cook Book. The meals were largely executed by former New York City Ballet soloist Antonio Carmena, a dancer who knew his way around a stage and a kitchen alike. “I always was going to the kitchen and would talk to my mother while she was cooking,” says Carmena, whose love for cooking began in his native Spain. “I would learn by watching her.”

Attracted to the fine balance of technique and creative expression that both practices demanded, Carmena enrolled in a course at the French Culinary Institute to quell his restlessness while recovering from a dance injury. Carmena was especially attracted to the unexpectedness of the cookbook’s recipes, such as Diana Adams’s Southern fried chicken in buttermilk spoonbread. Adams, as Wenzel points out, “was known for appearing in modernist Balanchine masterpieces that were stark, sleek, and simple.” What’s more, “the cookbook shows a side of these dancers that you don’t normally hear about,” Wenzel says. “It humanizes these monumental figures.”

The dancers’ stories struck Wenzel and Carmena the most, though. Within its pages lie tales of the late French dancer Violette Verdy, who grew up and trained by candlelight in Nazi-occupied France. The artist continued to cook her maman’s recipes while touring in the United States, traveling with cloves of garlic in her suitcase. To this day, Harlem native Arthur Mitchell eats his mother’s peas ‘n’ rice recipe every New Year’s Eve. And one anecdote recalls how Allegra Kent once brought back Wil Wright’s Ice Cream on a plane (via cabin freezer) from her native California for her family.

As Carmena describes, many of the recipes are not for novice cooks. Nor are they for the faint of heart: Loads of butter, bouillon, and heavy cream make hefty appearances in the cookbook’s dishes. Other recipes involve old-fashioned techniques, too. For example, Balanchine’s kulichi, a traditional Orthodox Easter bread, requires 45 to 60 minutes of dedicated kneading. Others are quite potent. As Le Clercq cheekily wrote in the recipe for her “Great-Great Grandmother Blackwell’s Eggnog”: “The spoon stands upright as it is supposed to, but which causes you to fall down as you are not supposed to.”

Tucked in between decadent dishes like Kent’s ice cream cake and Verdy’s quiche lorraine, one also finds foods, gadgets, and cooking techniques still in vogue today. Balanchine included several different pickled mushroom recipes, for one thing. And former New York City Ballet principal Edward Villella’s Italian mother, who was a health nut, used a pressure cooker to prepare organic vegetables from a specialty store that they schlepped miles to from their Long Island City home.

At first glance, The Ballet Cook Book’s recipes may not seem resonant with a new generation enmeshed in the clean eating movement. Yet Le Clercq’s piquant prose is what pulls readers in, regardless of their age or culinary preference. “She was quite ahead of her time,” says Rosofsky. “You kind of feel like [they’re] sharing tips and techniques with you over coffee. It’s disarmingly personal and intimate.” In one story, for instance, Le Clercq describes how she adopted a Chemex in hopes of finally brewing the perfect cup of coffee. The secret—or so she and Balanchine hoped—was a 10.5-sized anklet sock secured by hairpins as the filter.

What’s also extraordinary about Le Clercq’s book is how it offered an intimate window into the lives of golden era dancers from the ‘30s-‘60s, who weren’t nearly as accessible to the public as today’s media-savvy performers. “Ballerinas at that time were a little bit more on a pedestal than they are today … if you read, for instance, [Alexandra] Danilova’s memoir, she talks about her idea of a ballerina and how you have this responsibility to your audience to be a little bit above and removed, and to always be glamorous,” says Holly Brubach, the author of Choura: The Memoirs of Alexandra Danilova, and who is writing a forthcoming biography about her friend Le Clercq. “Tanny was a harbinger of a new kind of relationship between a ballerina and her audience.”

Le Clercq’s relatability has attracted all kinds of readers, dancers and non-dancers alike. So much so that despite only being available in secondary markets, demand for the book is high. (Six years ago, both Rosofsky and Wenzel purchased copies for around $75 each, and used editions today sell for upwards of $600.) Luckily, Rosofsky is working toward bringing the storied book back into print. Eventually, she has plans to pen a new ballet cookbook featuring the stories and recipes of dancers of today, too. “I think that The Ballet Cook Book deserves attention and embrace for all it represents,” Rosofsky says. “It is still a remarkable living book today. It’s not just a time capsule.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook