How £100 Bought an Obscure British Actor 224 Years of Cake and Fame

Thespians, writers, and princes all dined on Baddeley cake.

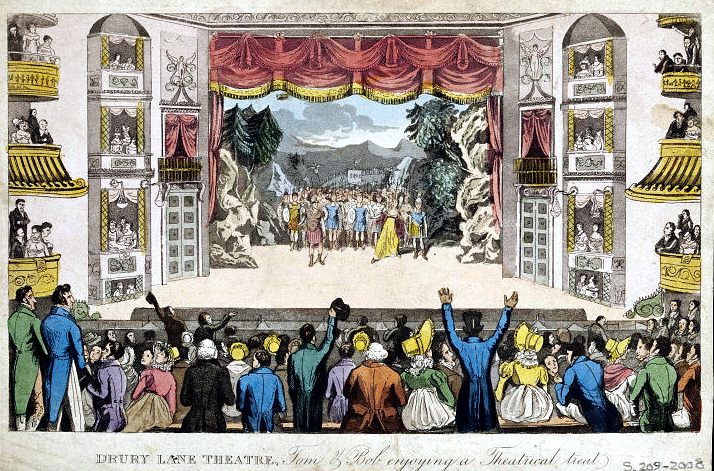

Robert Baddeley was never a leading man. Outshone by his wife—a famous actress of tremendous beauty, who eventually left him—he usually played the comic relief. And yet, since 1795, actors at London’s Theatre Royal, Drury Lane have toasted him every Twelfth Night with punch and a massive “Baddeley cake.”

How did this loveable lightweight achieve lasting fame? He paid for the privilege.

Not much is known about Baddeley’s early life, but legend holds that he was a pastry chef before he became an actor. In a spectacularly long will written shortly before his death, says Jennie Walton, the Drury Lane Theatrical Fund’s archivist, Baddeley instructed his executors to take £100 of his estate and invest it. Once a year, £3 would go to the purchase of wine, punch, and a Twelfth Night cake for the ladies and gentlemen of Drury Lane to enjoy in the green room forever after.

Twelfth Night is little-celebrated these days, but in Baddeley’s time, it was bigger than Christmas. Falling on January 5 or 6, it was reserved for revelry, games, and Twelfth cakes: fruitcakes covered in marzipan and topped with crowns. Each cake’s batter contained a dried pea and a bean, and finding one earned lucky eaters a coronation as King or Queen for the day.

The first Twelfth Night after Baddeley’s death was a bit somber. Walton recently received a newspaper clipping that recounts the evening. Over the phone, Walton reads from the January 8, 1795 issue of the Oracle and Public Advertiser: “Baddeley’s whimsical legacy was properly fulfilled on Twelfth Night, by the executors in the great green room after the first gloom from the mournful cause of the meeting had subsided.” (“In other words they were all thinking about poor old Baddeley,” says Walton.)

Spectacularly, Baddeley’s tradition has endured with little interruption, preserving a bit of Georgian-era London life in amber. The venue is still Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, which is also the oldest theater building in London, having been rebuilt after a fire in 1812. Over the years, Walton says, the ceremony has only been missed 13 times: during wartime, theater closures, and once when the performers were visiting from France. (“They wouldn’t give the cake to the French company.”)

While Baddeley’s will specified the cake be served in the green room on Twelfth Night, the presentation and ambience has varied. At times, actors devoured the cake on stage, or even between acts, snatching at the cake as they hurried by. On other occasions, illustrious guests attended. As Walton notes, the autobiography of Joseph Grimaldi, a wildly popular entertainer and the patron saint of modern clowning, describes his experience on Twelfth Night. Backstage, he saw Richard Brinsley Sheridan, a statesman, playwright, and longtime owner of the theater, jokingly peel the crown off the cake and offer it to the Prince Regent, the future King George IV. His Highness’s response was that he would prefer some cake.

The cake itself, Walton says, was often enormous, capable of feeding an entire theater company. One of the first pastry cooks to bake the cake was Samuel Birch, an actor and, later, Lord Mayor of London. Cakes were decorated lavishly with impressions of Shakespeare’s head or painted panels with scenes from the show. Periodically, actors toasted to the “skull” of Baddeley, for dreaming up such an exquisite affair. When Drury Lane was helmed by Augustus Harris in the late 19th century, people clamored for invitations to what was essentially a ball, with a supper, cake, and dancing. At one Baddeley cake ceremony in 1888, reported the New York Times, both Oscar Wilde and Alfred, Lord Tennyson, attended. The press covered the ceremony well into the 20th century.

These days, the events are smaller and rarely covered by the press, but the cakes remain glorious. Walton calls them “Disney-esque,” due to the show references baked in. Typically, the cakes are fruitcake, though a recent performance of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory called for a chocolate cake.

The 2019 celebration, however, will be the last Baddeley cake celebration for several years, and the earliest ever. On January 6, Twelfth Night, the theater will close for renovation. So on January 3, performers had their cake, themed around the current show, 42nd Street, in the theater’s Grand Saloon. There was also hot punch, made with a recipe Walton says is secret, passed down from theater manager to theater manager, and served in a silver punchbowl gifted by the original Drury Lane company of My Fair Lady. Walton doesn’t know what’s in it, but with the addition of several liquors, it’s certainly punchy. Until the theater re-opens, it will be the last punch toasted in honor of Baddeley’s skull.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook