Australian Soldiers Used to Write Letters Home on Crackers

They were easier to find than paper.

Sailors and soldiers throughout history have relied on hardtack. These dry, compact crackers could survive long voyages and military campaigns without molding or disintegrating. (Although maggots were still a risk.) Hardtack was such a feature of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC ) diet that it earned the nickname ANZAC tile (or wafer.) But they didn’t just eat it: Some Australian soldiers wrote messages on their ultra-durable wafers and mailed them home.

These crackers can keep indefinitely, and the Australian War Memorial (AWM) in Campbell, Australia, owns a collection of biscuit missives, many over 100 years old. “Army biscuits were notoriously tough,” says Nick Fletcher, head of Military Heraldry and Technology at the AWM. He compares them to clay tablets, and says they would often be soaked in liquid or grated into soup to make them edible. Made from flour, water, salt, and sugar, they were nearly imperishable once dried, which made them perfect for surviving posterity and the postal service.

Why send wartime messages by biscuit? The cracker postcards were sometimes sent out of whimsy. Combatants mailed them home as “a bit of a joke,” Fletcher says, to give their families an idea of what they were eating.

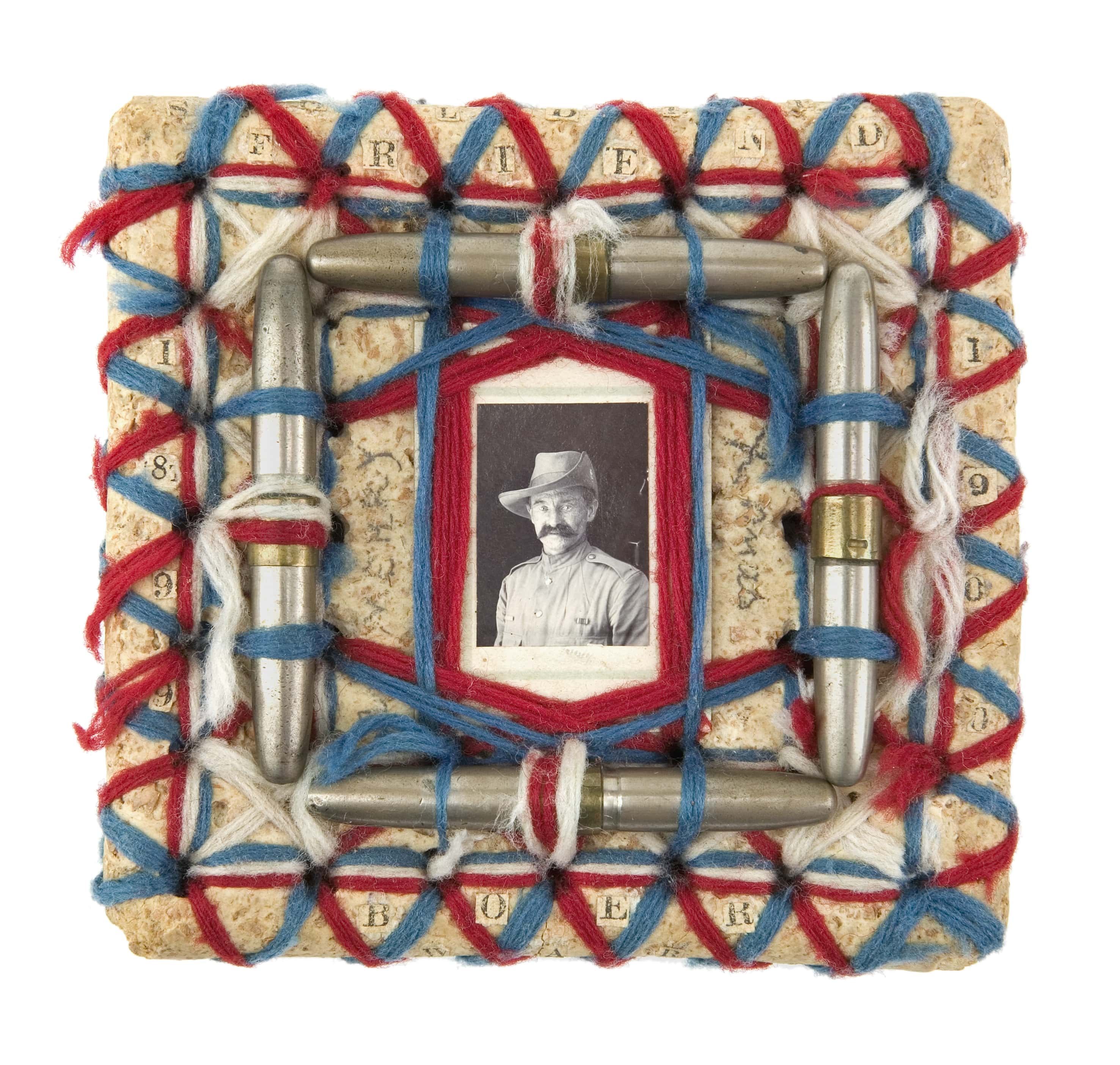

But it was necessity that most often led soldiers to write on hardtack. Fletcher says soldiers used cardboard, wood, and fabric to write home too, as paper was scarce on the front. The unknown sender of the above hardtack letter decked it out with wool yarn, cartridges, and pasted newsprint that reads “SOLDIER, FRIEND, 1899, 1900, BOER WAR.” A photograph of the magnificently mustachioed sender is bracketed with the words “MERRY XMAS,” written in pencil.

The Second Boer War, which ended in 1902, yielded a handful of edible cards in the Memorial’s Collection. But Fletcher estimates that the majority of biscuit messages date from the First World War, which began 12 years later. (A common joke is that some of the biscuits distributed to troops were leftovers from the Boer War, and Fletcher thinks it’s possible.) Even late in the First World War, the novelty of ANZAC tile letters hadn’t worn off, and soldiers occasionally sent them even when they had paper. Fletcher believes the practice was widespread.

The paper shortage was especially acute for ANZAC forces who fought the infamous Gallipoli campaign in what is now Turkey. According to Fletcher, the paper available “tended to be in urgent demand for toilet purposes, with letter writing coming a close second.” A number of combatants were killed by dysentery and other gastrointestinal issues because of limited sanitation.

This letter was sent from Gallipoli in 1915 by Cecil Robert Christmas, a member of a medical unit. Most of the surface is covered with the manufacturer’s stamp. The bottom edge reads “OLD FRIENDS ANZAC,” and a note on the back wishes the recipient a merry Christmas and happy New Year. Christmas (the man) survived Gallipoli to be wounded in France the next year, after which he returned to Australia.

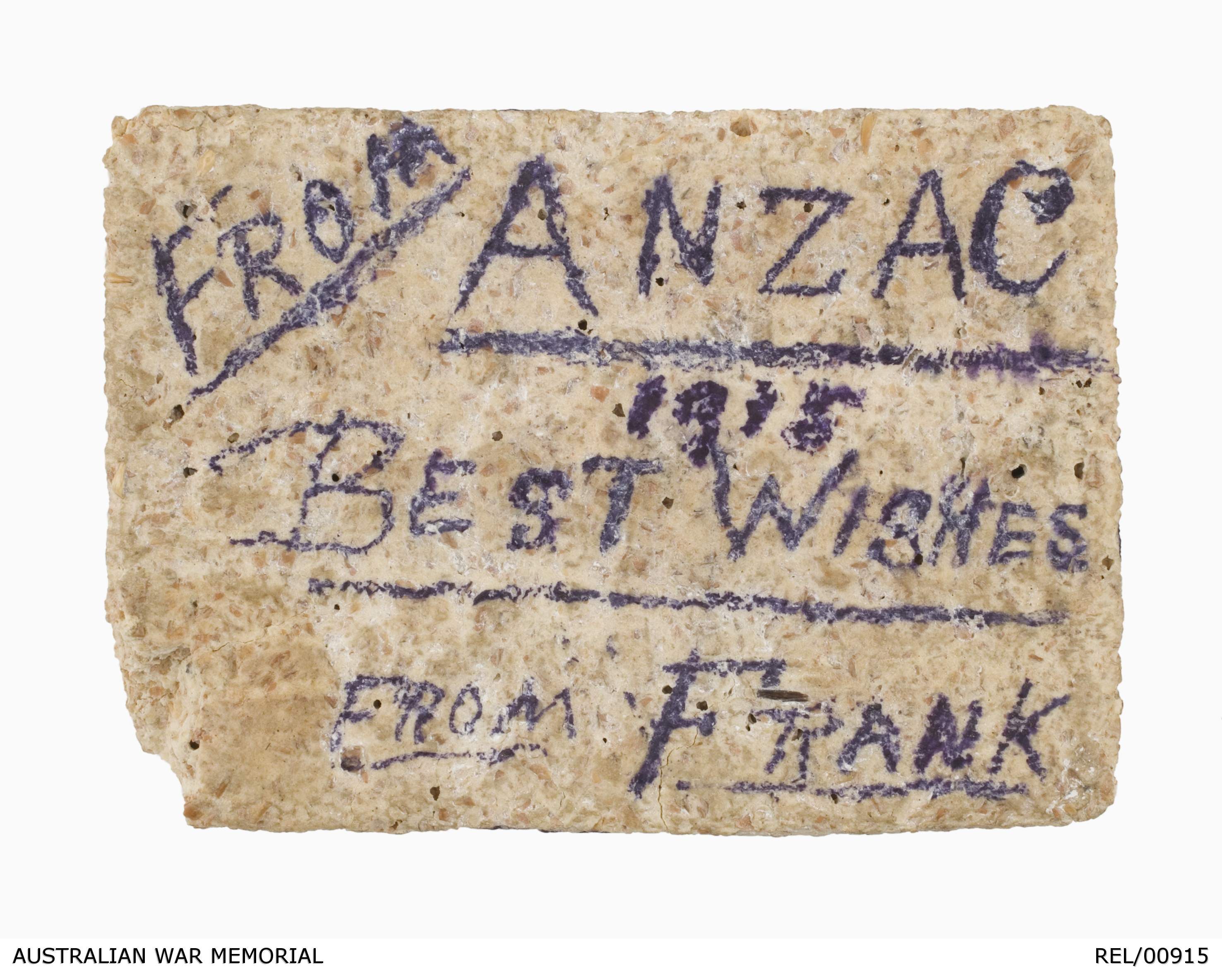

Some hardtack-inscribers were lucky. This cracker card was sent by Frank Lemmon, who emigrated to Australia in 1911, to his mother in Sussex, England. (Frank’s father was the unfortunately-named Orange Lemmon.) One side of the cracker is addressed to Sussex. The other reads, “FROM ANZAC, 1915, BEST WISHES FROM FRANK.” Frank survived Gallipoli and a long illness to make sergeant and, post-war, marry his English sweetheart.

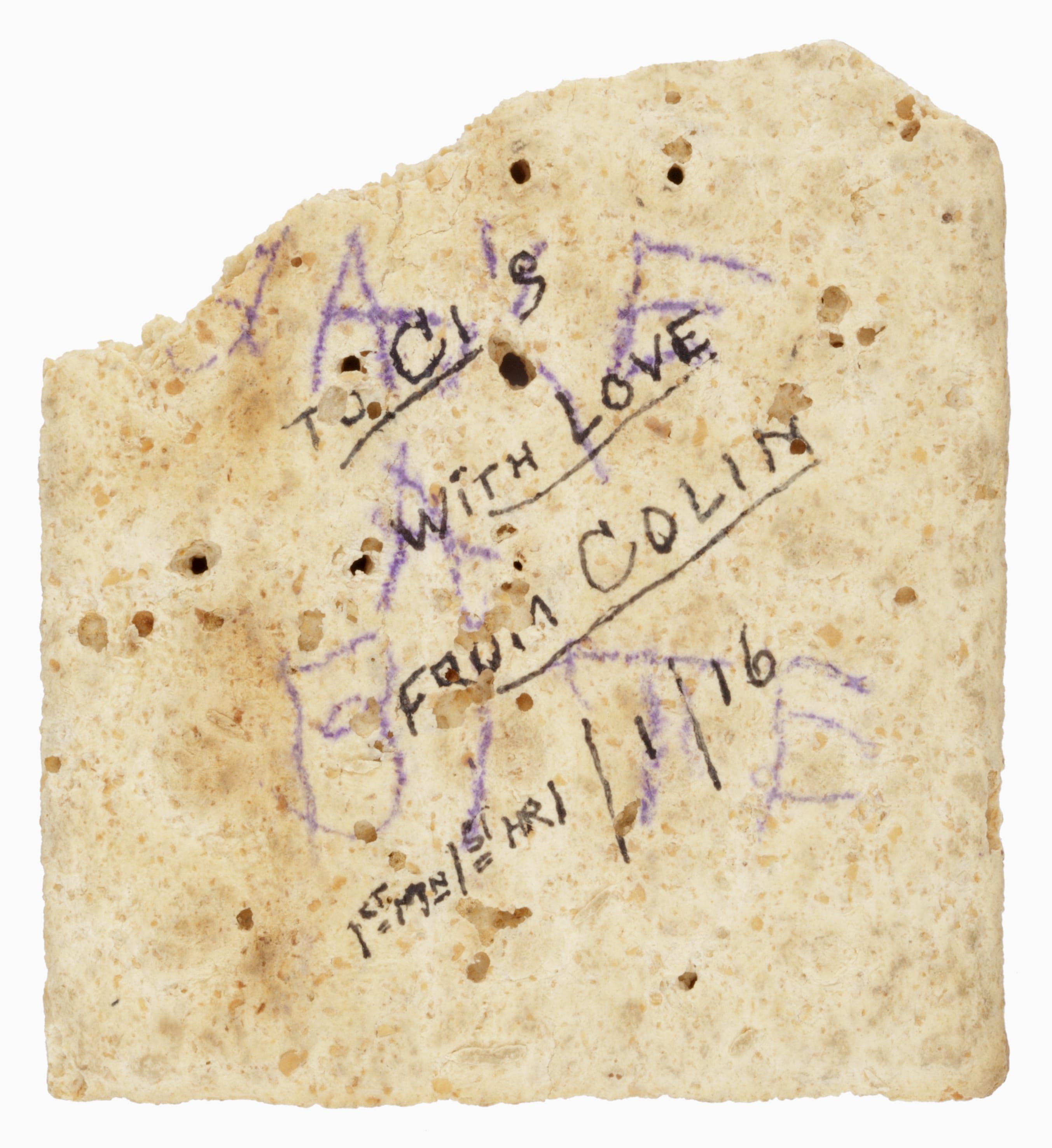

Other soldiers weren’t as fortunate. This wry cracker was inscribed in the first minute of 1916 by 18-year-old David Colin Grumont. Sent to his sister, the note reads “TO CIS, WITH LOVE FROM COLIN.” In typical sibling manner, Grumont scrawled “HAVE A BITE” over his note in purple. Grumont sent the note while training in Australia. In 1917, he was gassed in battle, and, in 1918, he was killed by a shell in France.

Biscuit letters were a bright spot in otherwise dark conflicts. This elegant cracker card, painted with a tropical island scene, was sent during World War Two. Made in 1945 by a soldier who, pre-war, was a sign painter, it was sent home by Captain David Keith Hanson. A short ditty on the back reads, “GOOD LUCK TO YOU, FROM US AT ‘TOL’, WE’RE SENDING THIS, (WE’LL RISK IT). XMAS CARDS ARE VERY SCARCE SO WE WROTE IT ON A BISCUIT.” Tol Plantation in Rabaul, Papua New Guinea, was the site of a massacre of Australian soldiers by Japanese forces. Hanson was a member of the Australian War Graves unit, tasked with finding and burying the 160 Australian soldiers killed three years before.

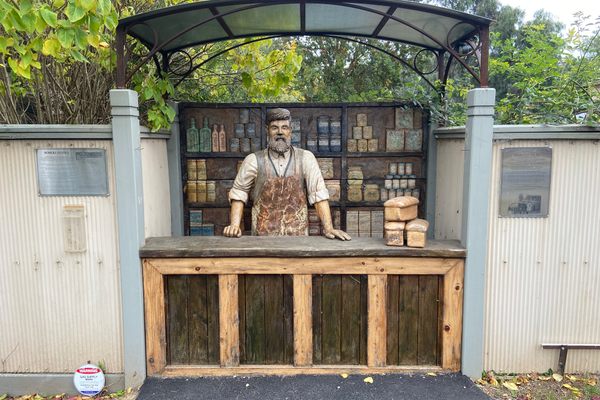

These days, army-issue crackers aren’t durable enough to send through the mail (which is probably a good thing). But if you have a hankering to try ANZAC tile, or to mail one, the AWM has an authentic recipe. Otherwise, you can make the other kind of ANZAC biscuit: the delicious oat cookies named in honor of the troops.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook