Assam’s Unique Mobile Drama Tradition Takes the Stage in a Changing World

These inventive traveling theater troupes were contending with shifting tastes even before the pandemic.

A spotlight pierces the darkness and reveals swathes of cloth fluttering on a makeshift stage. A model of a ship—flat, made of wood, but with a recognizable silhouette—floats in the center. After the model passes, we see a man and a woman climb a small fragment of the bow of a ship, her arms outstretched as he supports her from behind. An iconic soundtrack blares through the speakers, and the packed house whips into a frenzy. This was nearly two decades ago, when Assamese playwright Hemanta Dutta staged a theatrical adaptation of James Cameron’s 1997 blockbuster Titanic to jubilant reactions. It was the most attention-grabbing moment for a long-standing theatrical tradition in this state in northeastern India. It was produced on a miniscule budget by Kohinoor Theatre, a traveling troupe of a kind intrinsic to Assam.

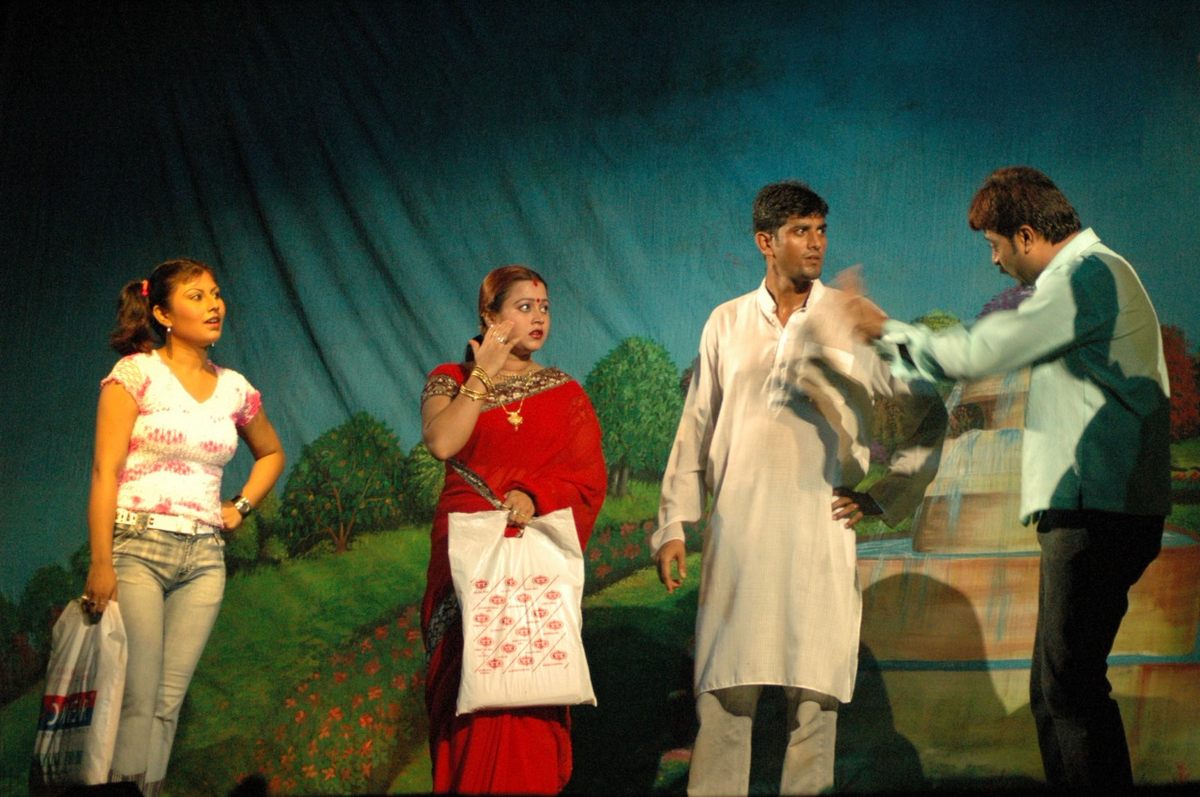

Bhramyaman, as this form of local theater is known, like many forms of live performance, is facing stiff headwinds from both the pandemic and the proliferation of entertainment options available to rural Indians. Each of these groups—there are dozens in Assam, performing in several languages—travels across the state from August to April. They bring with them everything they will need—about 120 people, including producers, actors, dancers, singers, technicians, drivers, and cooks, in addition to all the stage infrastructure to perform anywhere. A troupe sets up for three days—a different show each day—before moving on to the next makeshift venue. The prominent ones might hit 75 locations in a season, and they’ve had a profound impact on Assamese culture for generations.

The Hindu epic The Ramayan, for example, which follows the life of an exiled, divine prince who saves his wife from demon king Ravana, is best known to Assamese people not from the insanely popular 1987 television treatment, but from the adaptation put on by Kohinoor Theatre. “I have met people who have told me that they loved our Ramayan more than the [television] series,” says actor Bhobesh Boruah, who played Lord Rama himself on stage in the early 1980s.

More than 65 percent of Indians live in rural areas without reliable electricity, not to mention established entertainment venues. In some parts of India, this led to the rise of traveling cinemas. In Assam, however, a state connected to the rest of the country only by a narrow corridor, bhramyaman filled that need.

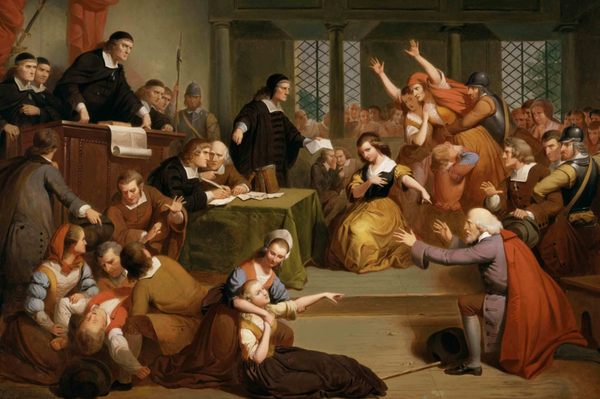

The dramatic tradition of Assam has deep roots, and has long had local identity at its core. In the 15th century, social and religious reformer Srimanta Sankardev conceived ankiya naat, a form of one-act plays that helped spread his philosophies. This involved musicians with folk instruments, and dancers, singers, and actors in elaborate costumes. During the 19th and 20th centuries, theater began to take more contemporary forms—from religious to romance, comedy, and drama, but still holding on to traditional folk themes. This was the birth of bhramyaman—a blend of the modern and the traditional. “It’s a combination of all these categories and more,” says Rituparna Patgiri, who teaches sociology at Delhi University and studied bhramyaman for her doctoral thesis.

The modern version of this tradition can be traced to 1963, when late Assamese dramatist and actor Achyut Lahkar started the Natraj Theatre that he founded in Pathsala, a small town about 64 miles west of Guwahati, the state capital. Today, most major troupes—Kohinoor, Abahan, Hengul—are still based out of this small town, popularly referred to as the “Hollywood of Assam.” “When he began, Lahkar’s idea was to showcase indigenous content that was characteristic of Assam,” says Patgiri. “It became about Assam and Assamese identity.” During those years, most plays were based on stories by Assamese writers, such as Bhabendra Nath Saikia, Lakshmi Nandan Bora, and Lakshminath Bezbarua, a giant of local literature.

These Assamese stories were central to the practice—in particular because Assam did not have much of a native film industry in the 1960s and the 1970s. To expand their repertoires, the troupes then began to stage adaptations of various Greek, English, and German stories: The Iliad, The Odyssey, Hamlet, Othello, The Threepenny Opera. From the 1980s, the film industry—in India and beyond—began to have greater influence on the choice of shows; Sholay (one of the best and most popular Indian films of all time), Ben-Hur, Tarzan, and Godzilla were introduced to Assamese audiences on stage.

Over time, the troupes have become beloved local institutions. Every village or town has its own theater committee to invite troupes and sell tickets. (They don’t need to work very hard on that, the whole calendar is usually a sellout.) Both troupes and committees are known to spend extra profits on local development projects, including schools, temples, and other social welfare organizations. This, and the fact that crew members are usually hosted by local families, has formed tight bonds. “It became a festival of the Assamese people,” says the actor Boruah, with the attendant atmosphere, including balloons, ice cream, and local food vendors. A newer addition: selfie booths for interacting with the actors. “This makes the mood itself so much more participatory and helps in retaining their loyal audience,” says Patgiri.

The sense of communal purpose didn’t exactly last. In the early 2000s, around the time that the Titanic adaptation garnered attention beyond Assam, award-winning local director Munin Barua delivered several hit films. Bhramyaman then began to hire more “stars” from films, and bring in more elements from mainstream Hindi and Tamil films, often at the expense of the indigenous stories it was built on. “It was a poor replication. There was a lot of violence, item numbers, and bike and car sequences on stage,” says Guwahati-based actor and lawyer Zerifa Wahid. “It sold like hot cakes for a few years but soon a certain section, especially the older generation, didn’t quite appreciate it.”

Systemic hierarchies within the system also became more pronounced and visible. Both Wahid and Boruah note that salaries for popular actors have been rising, leading to higher ticket costs and waning interest. “Earlier a family used to watch theater all three days, now they watch one day,” Boruah says. “Producers have increased the rates because they have to pay the stars.” In addition, male actors tend to push around established female actors for fear of losing the spotlight, Wahid says.

All this was taking place against the increased penetration of the internet and other entertainment options into villages. Then came the pandemic.

Prastuti Parashar is an actor in films and a megastar of mobile theater who recently took over as producer of Abahan Theatre, with the aim of revitalizing it, including through stories that would connect with Assamese audiences. Before the pandemic, the gregarious 39-year-old produced and starred in the play Mula Gabhoru, about a local Ahom warrior princess who fought an invading Mughal army. Just as she was settling in the role as the face of her theater, COVID-19 became the only story around.

“I can’t explain to you how badly I have been affected. I have to run the show… I have several loans,” she says. And contracts have already been signed for the current season. “Everyone is bound by this contract. When missed, the system collapses,” she says. She’s holding out hope something can be salvaged. “It needs to start. It’s alright even if it’s a little late but if it doesn’t happen at all, then we will all suffer a collective depression.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook