The Enigmatic Art of America’s Secret Societies

It’s not a fraternal order without some Illuminati imagery.

In the aftermath of Justice Antonin Scalia’s death at a Texas ranch, there was one particular detail that received much attention (including here at Atlas Obscura): The night he died, he had been in the company of a secret society.

Fraternal organizations such as the one associated with Scalia—the International Order of St Hubertus, an all-male elite hunting club—have much in common. They usually have a defined purpose, an exclusive membership, an initiation process, a motto and an emblem. They also share the perception of being shrouded in mystery, with secret handshakes, elaborate costumes and clandestine meetings.

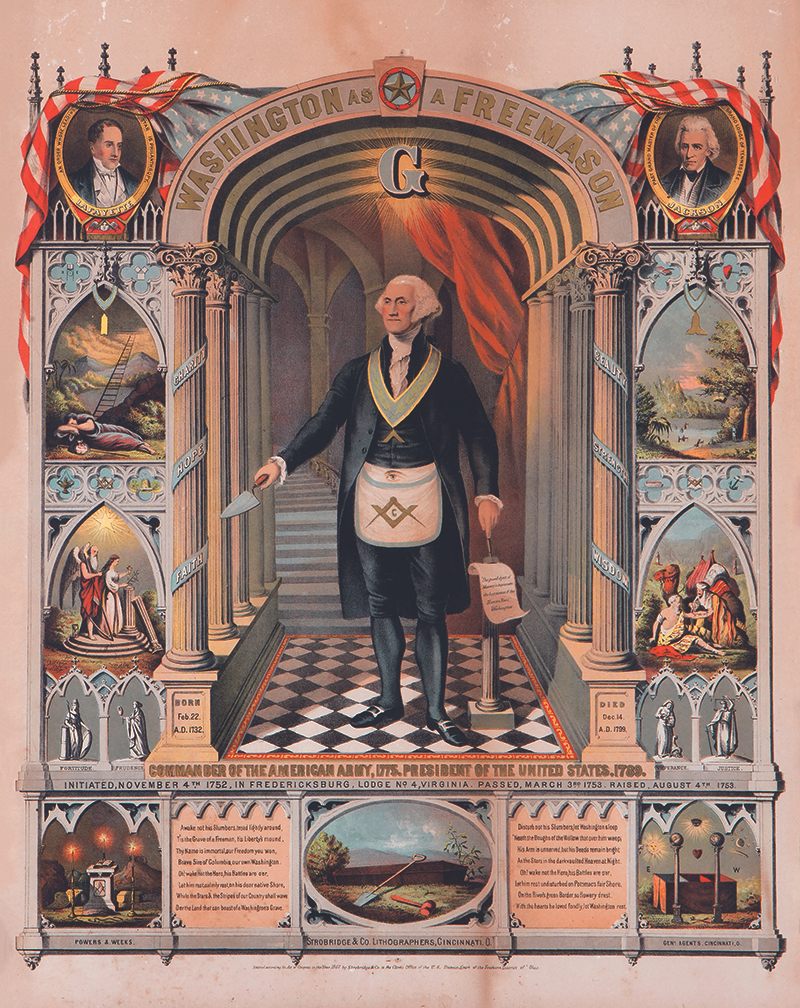

In America, freemasonry was established by the mid-1700s, when George Washington became a Master Mason. But it was in the late 19th century that the popularity of orders exploded. Known as the “Golden Age of Fraternalism”, there were an estimated 5.5 million members participating in an array of different societies.

Openness and inclusivity, of course, were not values of fraternal orders. Largely denied membership, African-American men formed parallel societies such as Prince Hall Freemasonry, which was first founded in 1776, and independent organizations such as the Knights of Tabor, in 1846. Women were excluded as well, until the International Order of Odd Fellows created a female branch, the Daughters of Rebekah, in 1851.

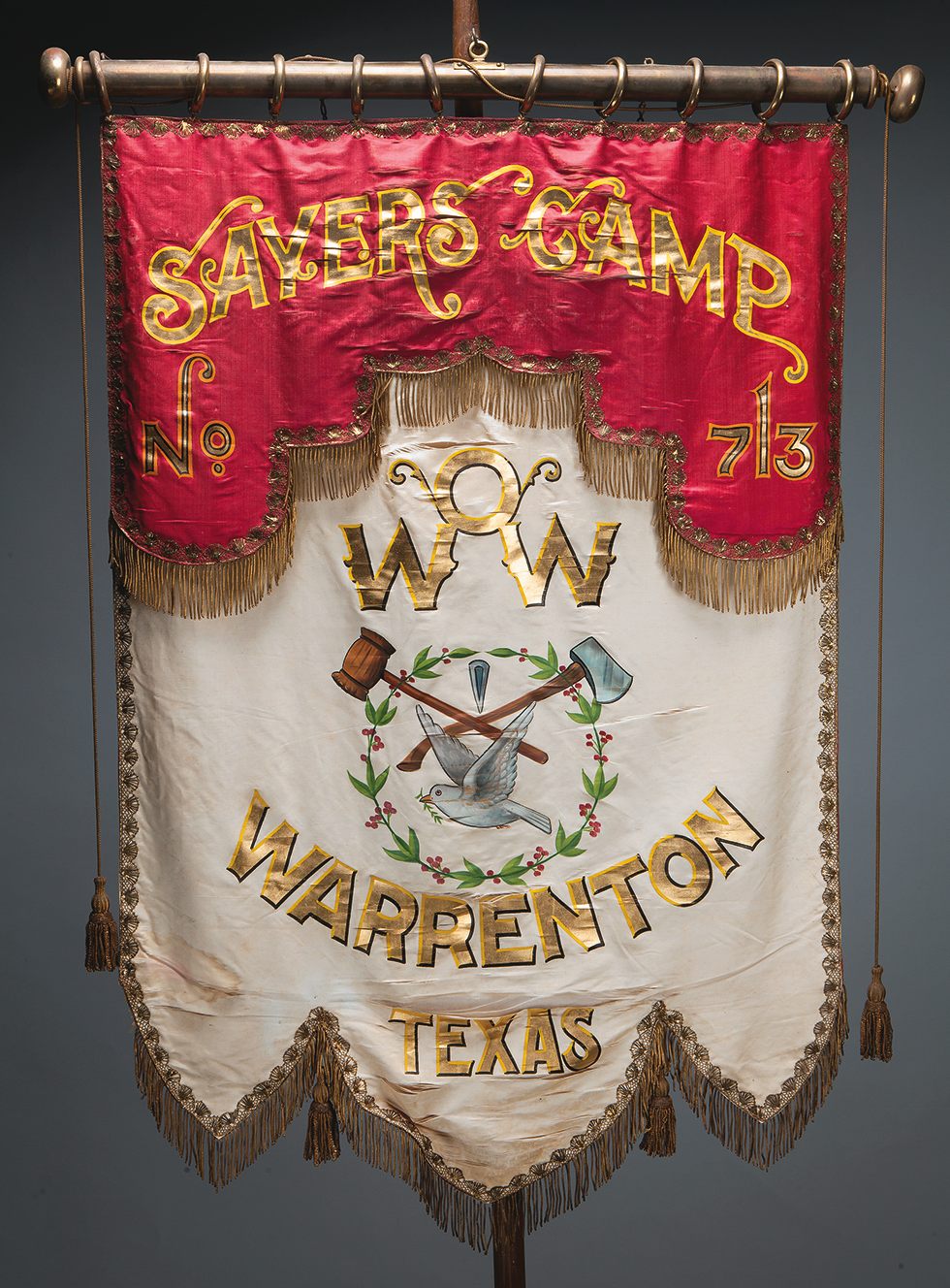

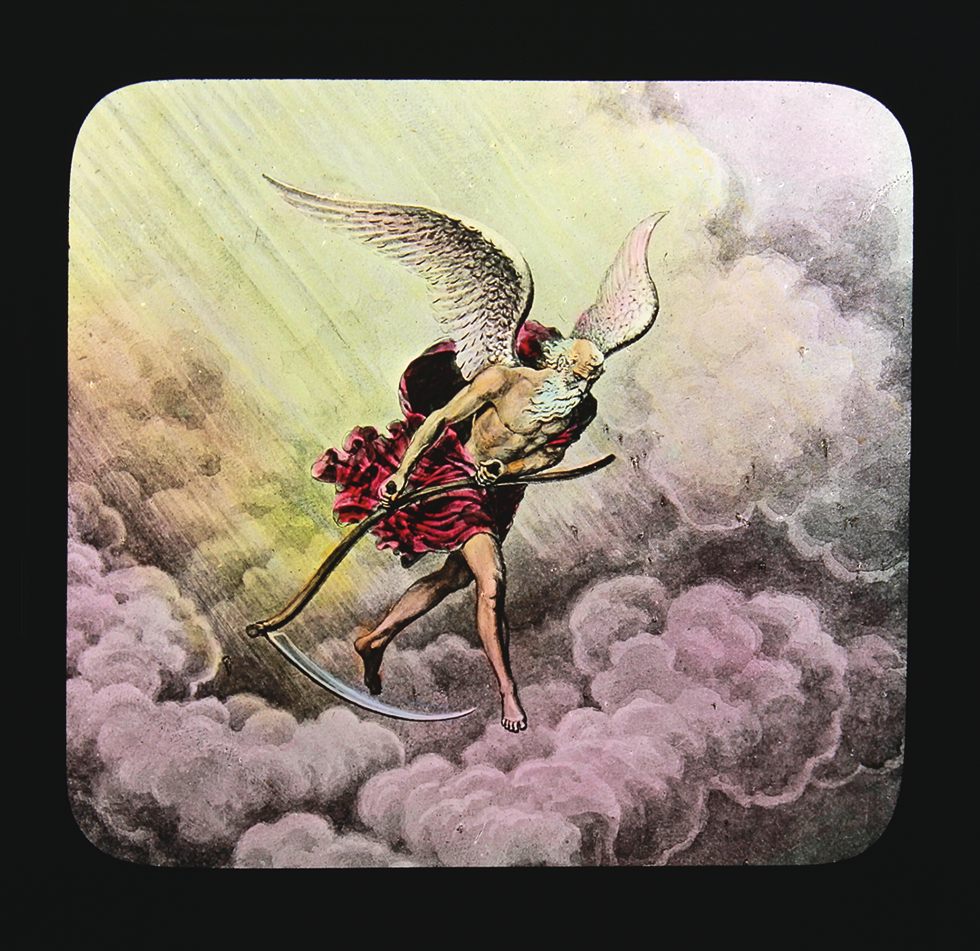

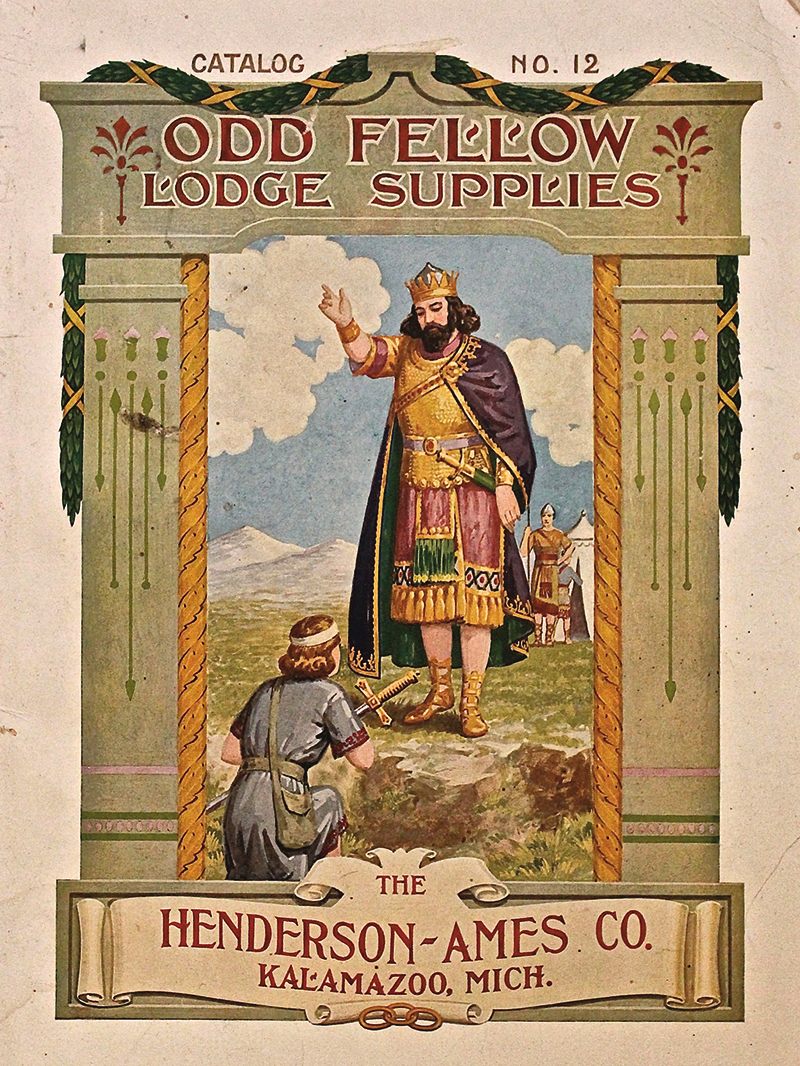

What unified all these different groups, though? Aesthetics. With the growth of membership came a rise in the creation of artwork, which is explored in the book As Above, So Below: Art of the American Fraternal Society 1850-1930. Divided into the types of imagery, such as banners, magic lanterns and ritual objects, the book also examines how new technologies, such as the invention of the chromolithograph, created new means of expression. Here is a selection of the most intriguing images:

George Washington as a Freemason, from an 1867 chromolithograph, Ohio.

Improved Order of Red Men, Daughters of Pocahontas degree team, in ceremonial costumes, Tahoe Council No. 99, San Francisco, 1910.

Woodmen of the World parade banner, c. 1900.

Father Time, hand-colored magic lantern slide, Freemasons, 1890–1900.

Henderson-Ames Company, Odd Fellow Lodge Supply catalog, c. 1910s.

Three Modern Woodmen of America, Cedar Point, Iowa, c. 1908.

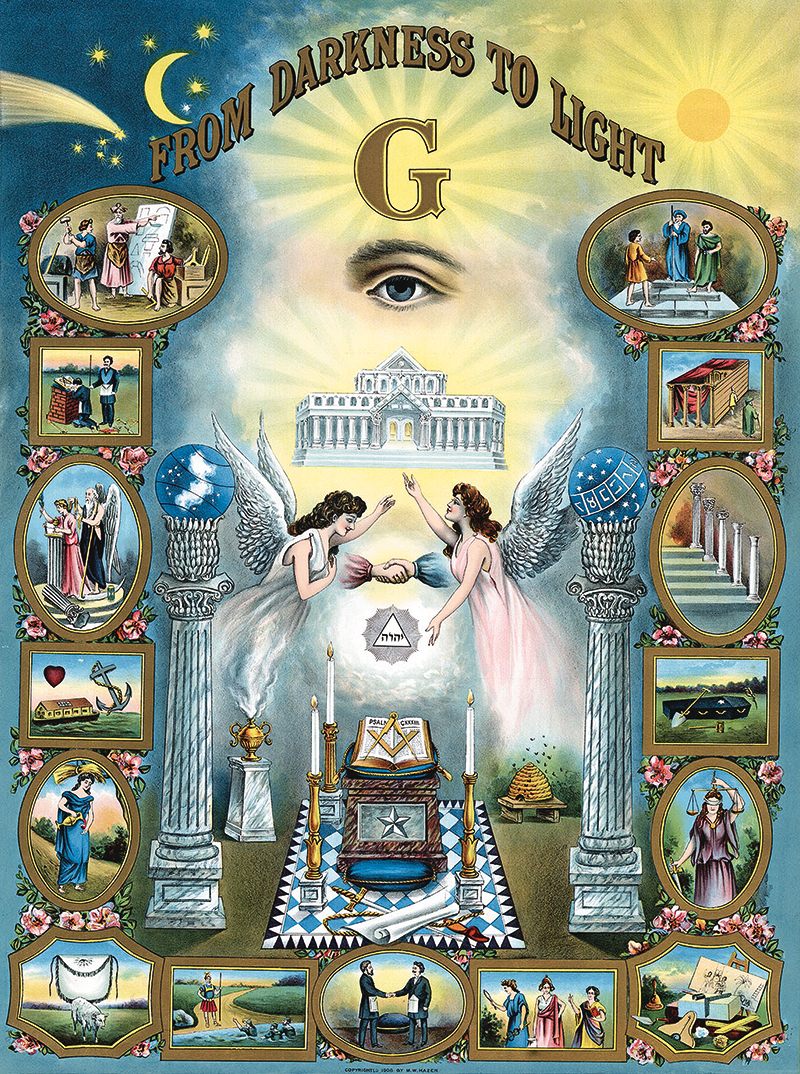

From Darkness to Light, 1908.

Masonic Scottish Rite painting, c. 1880–1890, from a southern Wisconsin lodge.

Modern Woodmen of America parade banner, c. 1900.

Rebekah lodge sisters in ceremonial costumes, Rock Valley, Iowa, c. 1900.

Odd Fellows heart-in-hand staff, c. 1890s.

Where Hideous Things Slither and Climb, hand-colored magic lantern slide, Knights of Pythias, 1890–1900.

Woodmen of the World gathering at Mineral Wells, Texas, 1911.

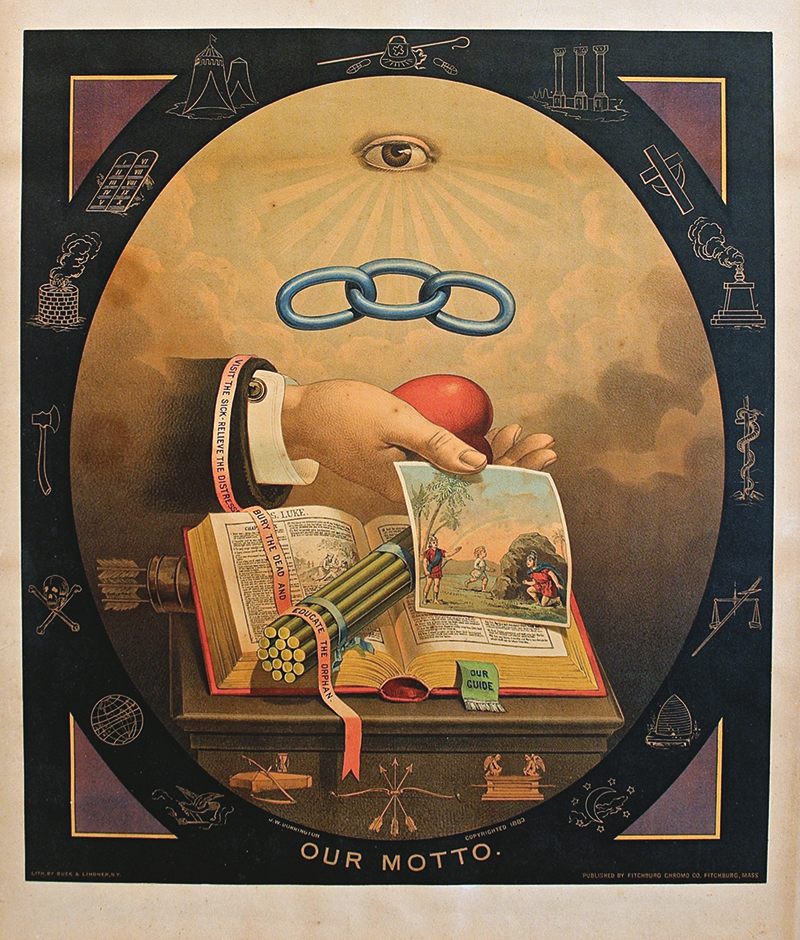

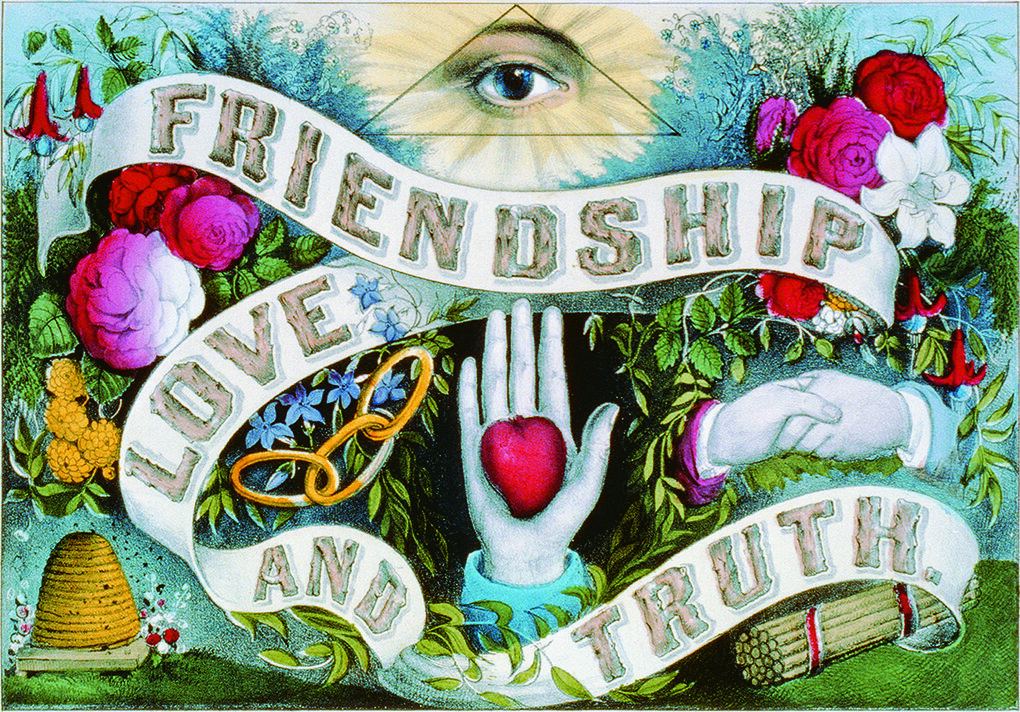

Independent Order of Odd Fellows, Our Motto, 1883, by J. W. Dorrington.

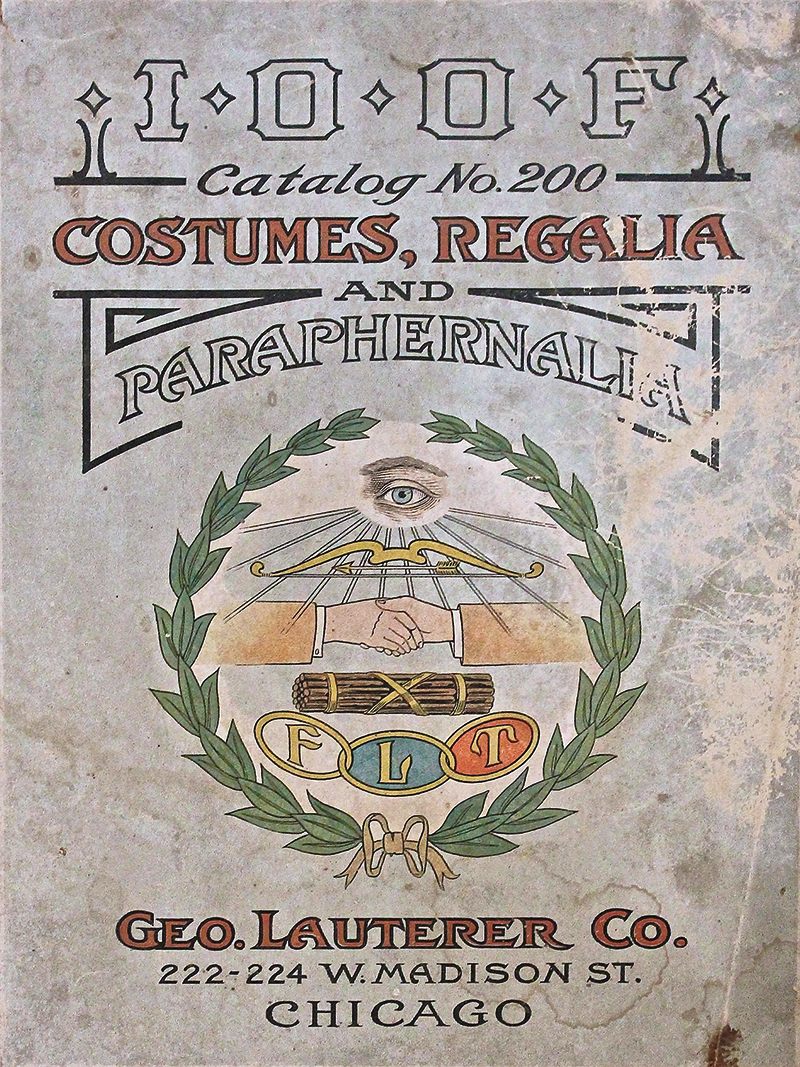

George Lauterer Co., Odd Fellows supply catalog, c. 1900.

All-Seeing Eye of Deity, hand-colored magic lantern slide, Freemasons, 1890–1900.

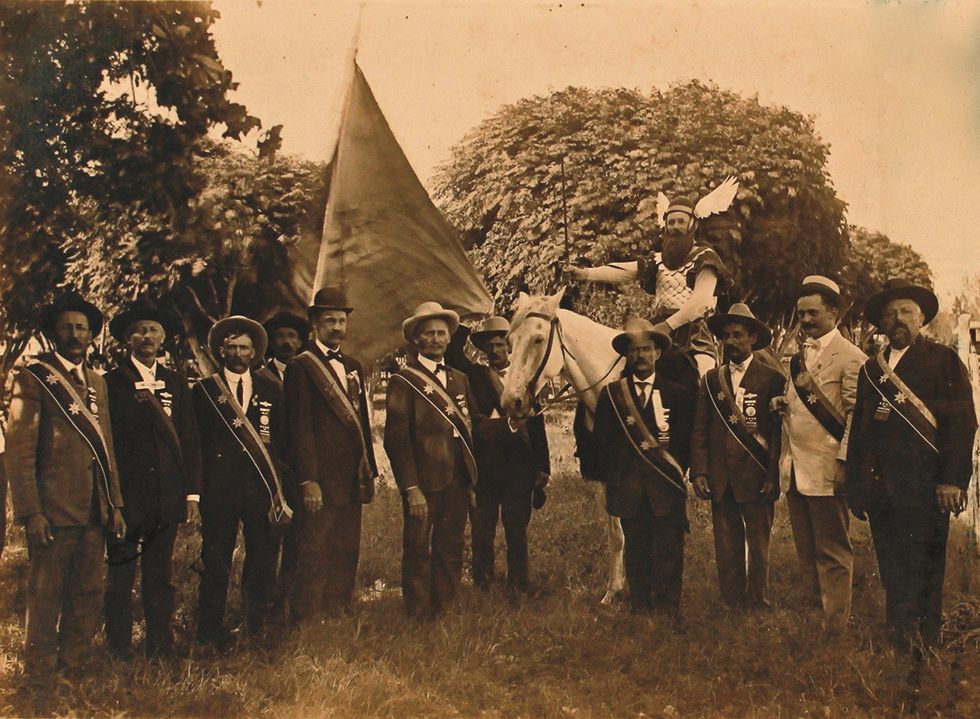

Sons of Hermann lodge members dressed for a parade, Shiner, Texas, 1909. The man on horseback is wearing a Thor costume.

Rebekah souvenir, 1872 from Cincinnati, Ohio.

Odd Fellows Initiatory degree banner, 1880s.

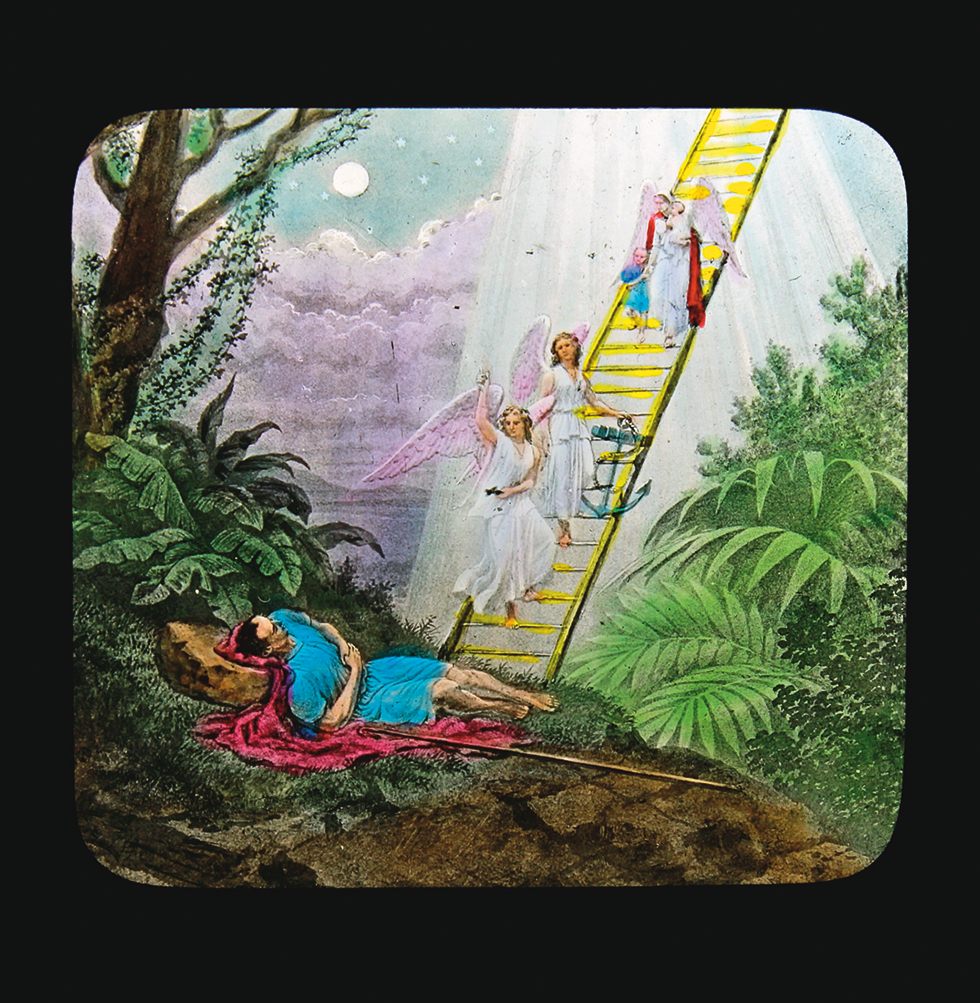

Jacob’s Vision, hand-colored magic lantern slide, Freemasons, 1890–1900.

Knights of Pythias lodge officers in ceremonial regalia, Frankfort, Indiana, c. 1900.

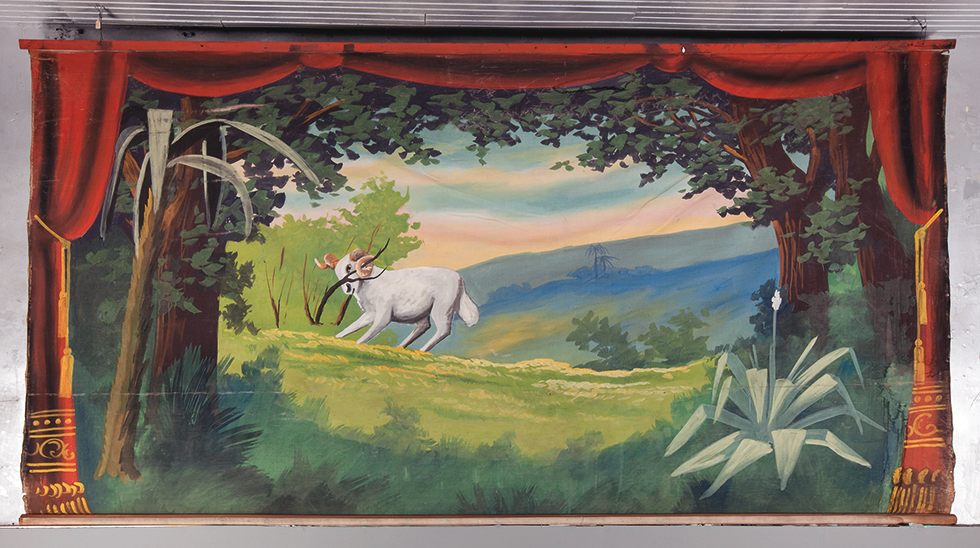

Odd Fellows scenic painting, c. 1900.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook