The Artist Shrinking Antarctica’s Glaciers

Using 3-D imaging, Helen Glazer brings the southernmost continent indoors.

One cold day in the winter of 2014, the American artist Helen Glazer found herself in the corner of a parking lot in her home state of Maryland, taking photo after photo of a dirty snowbank. “It was probably about six feet high, and about 25 feet wide,” she says, and it was marbled with grime and imprinted with plow tracks. She walked around it slowly, capturing it from all angles.

Glazer, whose body of work stretches across media and over decades, is fascinated by natural forms. She has made murals based on constellations, stark portraits of branching trees, and prints of cloud formations, hand-colored to give them extra pop. While the snowbank she photographed eventually got its own sculpture—a scaled-down replica about the size of a shoebox—it was a means as well as an end: Glazer was working up a new project idea, and she needed something that could stand in for a glacier.

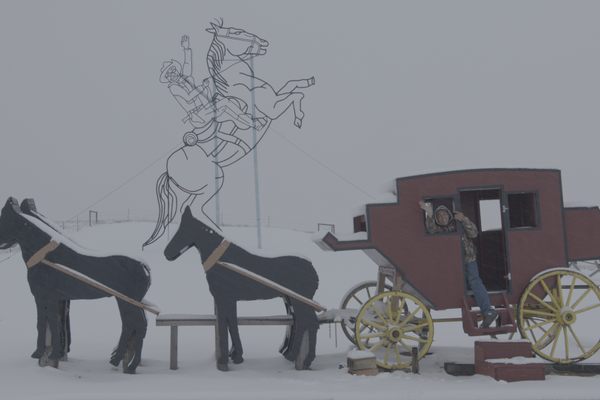

Fast forward three years, and Glazer has visited real glaciers. As a participant in the Nation Science Foundation’s Antarctic Artist & Writers Program, she has also created scale models of them, along with similar sculptures of strange rocks and pressure ridges; narratives of field camps and mummified seal mysteries; and mesmerizing photographs of frozen harbors, ice tongue caves, and, of course, penguins. All come together in an exhibit called Walking in Antarctica, currently on display in the Rosenberg Gallery at Baltimore’s Goucher College.

The southernmost part of our planet is also among the most mysterious. As Glazer points out, until recently, “nobody ever lived in Antarctica.” It has no native populations, and the first ship didn’t land on the continent until 1895, when a boat full of Norwegian whalers decided to venture slightly farther south than usual.

Indeed, for much of human history, people barely knew it was there—a strange fate for a land mass the size of the U.S. and Mexico combined. “If you look at globes from the 19th century, a lot of times you’ll see a few little lines,” Glazer says, “and [the cartographers] will have just written ‘frozen ocean.’”

Before Glazer herself set foot on the continent, she had her own preconceptions. “I asked myself, ‘What would an artist do there?’” she says. “I thought every photo would be a blue rectangle on the top and a white rectangle on the bottom.”

As other artists have found, the truth is much more three-dimensional. In the early days of exploration, painters, filmmakers, and photographers were a vital part of most Antarctic journeys, capturing the imposing glaciers and adorable penguins that inspired patrons to keep funding trips. More recently, the Antarctic Artist & Writers Program has sent over dozens of creative types, who have returned with fodder for everything from children’s books to sonic installations.

As she began researching Antarctica, Glazer saw the landscape’s possibilities more clearly. She was particularly drawn in by pictures of the coast: “There were mountains, and there were all kinds of formations that the ice took,” she says. “I said, well, I could actually make sculptures of these forms.”

After she was accepted as a 2015 participant, Glazer spent seven weeks in Antarctica, where she sized up glaciers, explored an ice cave, and communed with a colony of Adélie penguins. Throughout, she meticulously documented her journey—through photographs, but also through blog posts, which she used to keep friends and family apprised of her adventures.

Their enthusiastic response, as well as later feedback from a local artist group, inspired Glazer to put together an audio tour, which exhibition visitors can tune into as they immerse themselves in the visuals. (It’s a fun listen from home as well: I especially like the aforementioned episode about the McMurdo Dry Valleys’ mysterious mummified seals.)

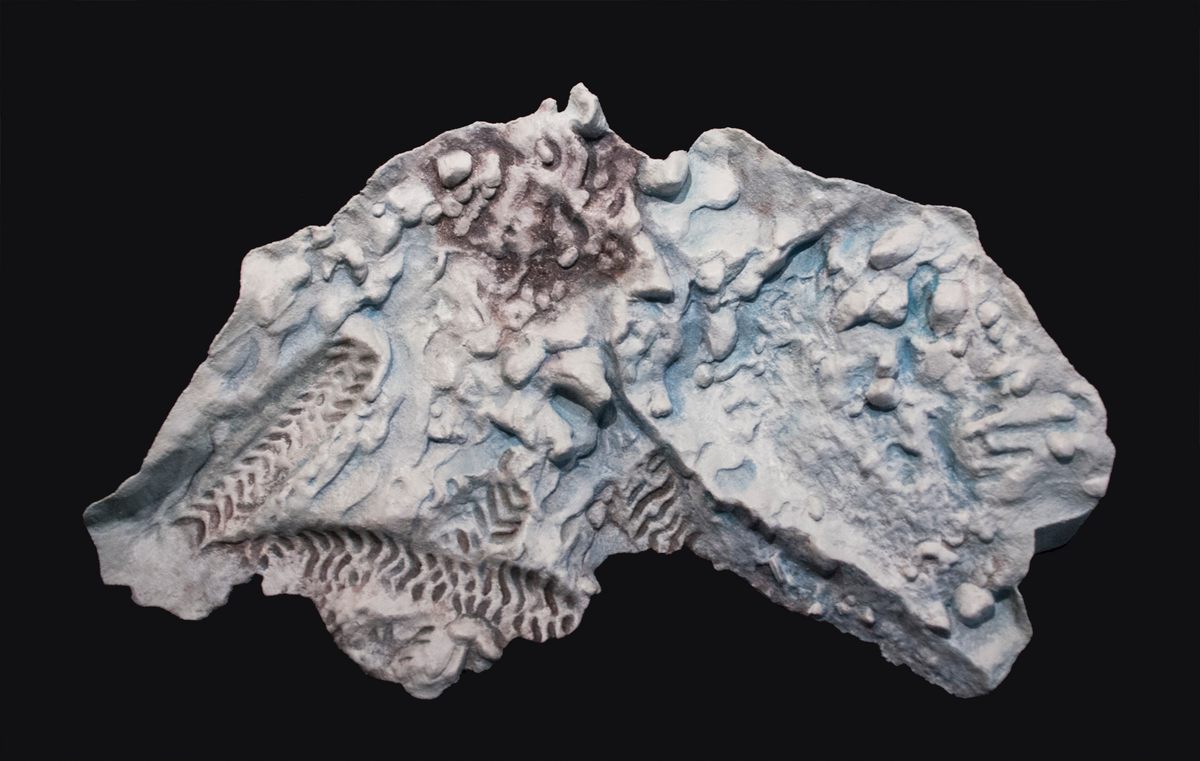

The centerpieces of the exhibition, though, are the four glacier miniatures—which are, to Glazer’s knowledge, the first sculptures to ever be made out of three-dimensional scans of the Antarctic landscape. Two depict sections of the Canada Glacier, and one is a pressure ridge near the Double Curtain Glacier on McMurdo Sound. The last is a ventifact, one of many such wind-eroded boulders that dot the landscape, and which Glazer nicknamed “Bird,” after its swooping shape.

“The ventifacts actually obey a cardinal rule of good sculpture: that it should present different forms as you walk around it,” she says in a clip from the audio tour. “Frankly, I don’t think the human imagination could ever come up with solutions to that challenge as unpredictable as these.”

A YouTube video details Glazer’s sculpting process, which involves taking hundreds of photographs of the object, scanning them into a photogrammetry program, and editing them together until they form the desired shape. She then 3-D prints the sculpture in chunks, pieces it together, and paints it.

As each form shrinks down small enough to be seen on a computer screen—whether destined to become a photograph or a sculpture—she thinks about her original encounter. “During my first field placement, I walked all the way around an iceberg and took pictures of it,” she says. “And it was huge! Really massive … I didn’t know that I’d be able to capture things as large as I did.”

By shrinking these massive landforms and transferring them into the more manageable space of a gallery, Glazer hopes to make Antarctica as a whole more accessible as well. As climate change has begun to take its toll on the continent, splitting ice shelves and accelerating seasonal melts, its various shifts and shrinkings have filled the news. “If these big ice shelves start collapsing, we’re going to see catastrophic sea-level rise,” says Glazer. “I didn’t meet anybody [in Antarctica] who wasn’t concerned about climate change.”

For the rest of us, though, it can be hard to grasp what’s going on. Even compared to its northern cousin, the Arctic—which is both more closely tied to human history, and is experiencing more obvious climate-related changes—Antarctica can seem rather slippery. “You have this place that’s very distant,” Glazer says. “It’s very easy to think, well, that’s kind of irrelevant to my life.”

“But now, all the research that has been done, and continues to be done, is making it clearer and clearer that all of this is connected,” she says. The longer she spent there, “the more I understood about how important it is to preserve it—to be aware that our actions will affect what happens there, and what happens there is going to affect what happens here.” For Glazer, one step in this preservation is sculptural: literally capturing the landscape, and bringing it to those who might never see it otherwise.

“Walking in Antarctica” is on exhibit through January 12th, 2018 in the Roseberg Gallery at Goucher College. You can view more photographs and artworks from the exhibition (and its predecessors) below.

*Update 12/18: This post has been updated with information about the size of the sculptures.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook