A Revived Museum Presents the Full History of Black America

America’s Black Holocaust Museum reopens in the historic hub of Milwaukee’s African American community.

The thick summer air of Marion, Indiana, was still on that awful night in 1930. A 16-year-old boy, weak and beaten, stood between the bodies of his two friends. The other Black teenagers had just been lynched, and a mob of townspeople jeered and chanted as a noose was placed around his neck and tightened. He closed his eyes and started to pray. The shouting swelled to a roar. Then a lone voice stood out amid the din. A woman pleaded for the people to stop, insisting the boy was innocent. The crowd quieted and the noose was loosened and removed. The teenager would not die that night.

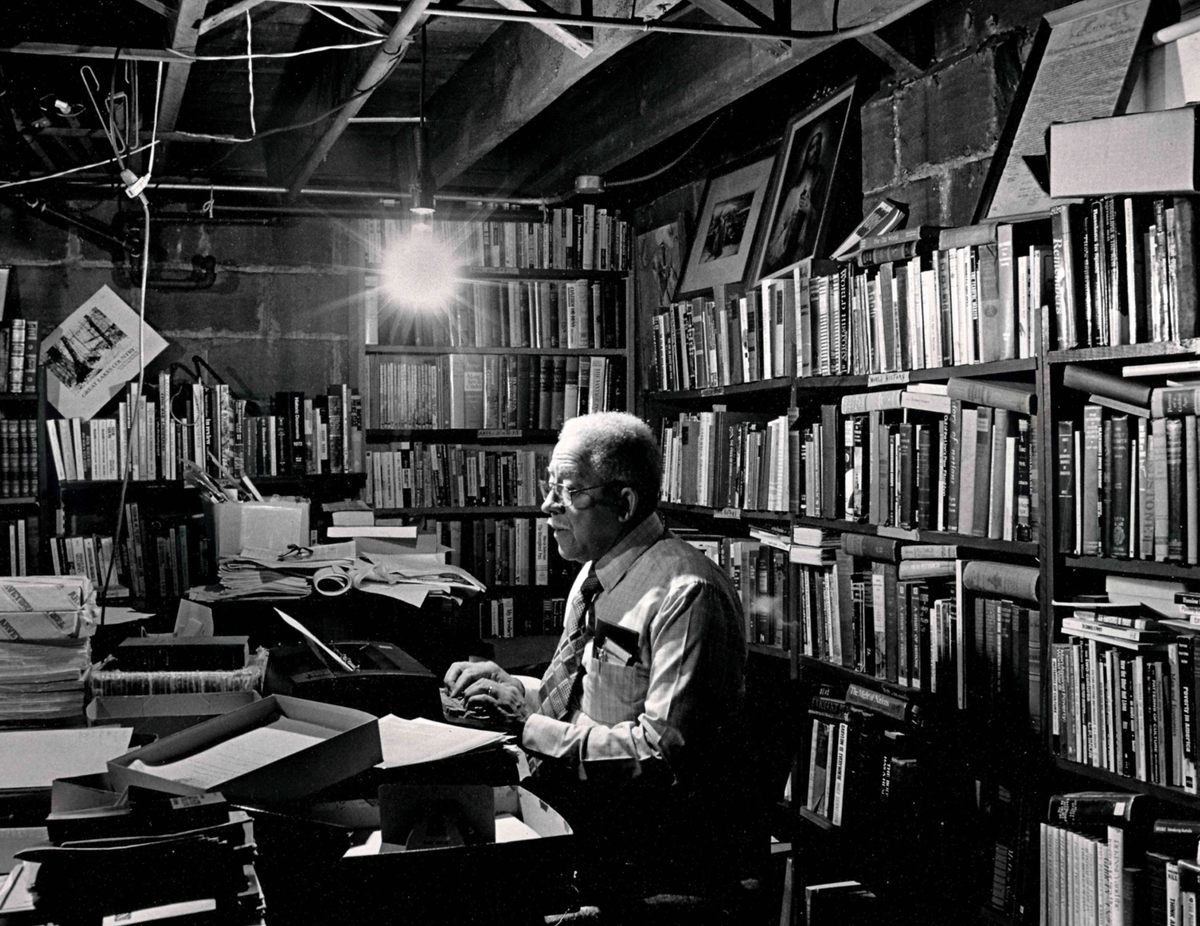

His name was James Cameron, and, as an adult, he would use the harrowing experience to fuel decades of activism, including the foundation of America’s Black Holocaust Museum, a project he began in his adopted hometown of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Inspired by a visit to Yad Vashem, the World Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem, Cameron resolved to create a space that would acknowledge the history of Black Americans, from its roots in the ancient civilizations of Africa to the present. Including the word “holocaust” in the museum’s name reflected parallels Cameron saw in the European Jewish and Black American experience. He believed that telling the story of Black Americans truthfully and in full would be a liberating force that would lead to what he called “real racial repair and reconciliation.”

The museum, first established in a single room in 1988, reopened in its own building in Milwaukee’s Bronzeville neighborhood in 1994 and was a Near North Side landmark for more than a decade. Cameron died in 2006 and, two years later, financial challenges forced the museum to close. It was revived as an online museum in 2012. Now, thanks to a decade of planning and a fresh infusion of funding, the museum is set to reopen in a new building several times the size of its previous incarnation. Its mission remains unchanged.

“I want people to understand that this is not a Black museum for Black people around Black history,” says Robert Davis, the museum’s president and CEO. “It’s an African American museum that tells African Americans’ experience in America through the lens of African Americans and through the voices of African Americans.”

Milwaukee, a city of about 600,000 that stretches along Lake Michigan, is a fitting location for the museum. In many ways, the Midwestern city encapsulates the challenges and tensions that the country is facing. As in many other cities, inequities in housing, education, health care, and employment opportunities are perennial issues; access to voting and tensions between the community and police are recurring problems. Milwaukee is also the most racially divided city in America. It sits at the top of the Brookings Institution’s index of metro area segregation with a score of 79.8 out of 100; on the scale, zero represents total integration and 100 indicates complete segregation.

Robert Smith, the museum’s resident historian and a professor at Marquette University, describes Milwaukee’s segregation as no less than a continuation of the violence that has been directed against Black people in America for centuries.

“You can think about violence as being perpetrated by the way that public schools are underfunded, how our municipal structures, highway structures, entertainment structures are built in ways that might disrupt communities,” says Smith.

The museum’s neighborhood, Bronzeville, is an example of that kind of disruption. For much of the first half of the 20th century, Bronzeville was a thriving commercial and social center for Milwaukee’s Black community. Beginning in the 1950s, however, a series of aggressive urban development projects, including the demolition of homes to make way for more expensive real estate, scattered Bronzeville’s population. Interstate construction then literally ripped the community in half: The new freeway bisected the neighborhood, largely following the course of what was once its bustling heart. Bronzeville never recovered.

Community members and city officials have undertaken a variety of projects over the last two decades to restore Bronzeville’s cultural identity and commercial success. Real estate agent Melissa Allen, one of the people dedicated to this effort, was also involved in helping ABHM find a new home. Asked why she feels the museum needed to be in Bronzeville, she says she thinks of her children.

“To have a museum that can contribute to the renaissance of the community and is dedicated to teaching about Black history, to me it means that they matter,” says Allen. “It validates their existence.”

Community members who knew Cameron personally say the museum is needed more than ever. Darryl “King Rick” Farmer II is the current leader of the Original Black Panthers of Milwaukee—revived about seven years ago after a period of inactivity, the group’s name is a nod to their deeper history, which goes back to the 1960s. Farmer’s friendship with Cameron began during that earlier period, when the latter served as an elder in the organization. Now, he hopes the reopened museum will shake up the city’s status quo.

“Some people are comfortable with the way that Milwaukee is, they want to ignore what has happened here. Well, that’s the problem,” says Farmer. “That is why we need this museum to show America’s ugly history, or nothing will change.”

Reopening on February 25, what would have been Cameron’s 108th birthday, the new space takes visitors through seven themed galleries chronicling the African American experience, including new exhibits detailing the Jim Crow era and Cameron’s life. Davis hopes the revived museum will serve as a springboard for connection as well as a call to action—just as Cameron intended.

“We want you to walk into the museum and actually become transformed as you’re reading the exhibits, as you’re doing interactive exhibits. We hope that you understand what people felt during that time,” says Davis. “After you have felt these things, these emotional things around our history, what are you prepared to do?”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook