All You Need to Play the Alaskan Lottery Is an Ice Guess

The Tanana River’s annual melt has thrilled gamblers for over a century.

For eight hours a day Mitch Duyck sits in a simple lifeguard-like tower in Nenana, Alaska and alternates between watching the clock and river outside his window. He’s neither slacking off nor hoping for a Disney-esque rescue. He’s waiting. Duyck needs to be there to write down the exact time the alarm goes off. A potential six-figure pay-out to some lucky Alaskan depends on it.

Alaska is one of five American states without a lottery (the others being Hawaii, Nevada, Utah and Alabama). The state also doesn’t allow slot machines or betting on most things, ranging from scratch-off tickets to horses.

But one thing Alaskans can bet on is when the breakup will happen.

Not the breakup of favorite celebrity couples or local politicians, mind you. Rather, the breakup of the ice on the Tanana River.

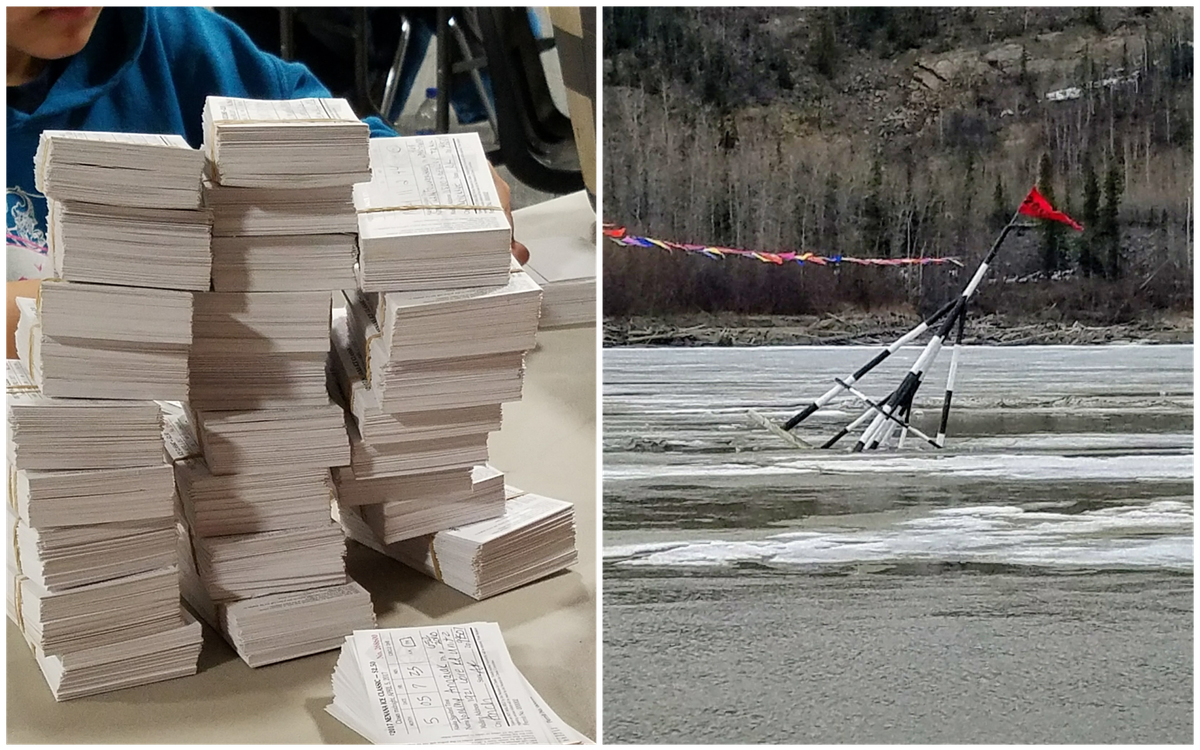

Each year since 1917 a 26-foot-tall spruce tripod has been embedded 300 feet from shore on the first weekend of March. Cables are attached to the tripod and rigged to a rope-and-pulley system attached to the tower. When the tripod has traveled 100 feet downriver, the antique clock is stopped and a flood siren sounds throughout the town, signaling the end of the contest and winter, a particularly long season in Alaska’s remote interior. For $2.50 a ticket, Alaskans (or those visiting Alaska) can place their bets on when the ice will melt enough for the siren to go off. Whoever guesses the closest minute wins. Duyck is just one of a group of guards who watch the tripod round-the-clock.

Last year an Anchorage-based woman won the whole $311,000 pot. In 2017, the 42 people with the right guess each received a payout of $4,584.75, after taxes (though those who entered as a pool had to split their winnings even further). The most number of correct guesses was in 1973, with 58.

The guessing game was developed 1917 by surveyors building the Alaska Railroad. It both helped them pass the time and stay vigilant of river conditions—big blocks of ice could potentially take out bridges. The original wager cost $1.00 (a sum that amounts to $20.21 today) and was only open to Nenana residents. But after a few years, word of the contest grew and attracted participants from across the territory.

Soon ticket books were distributed to grocery stores, gas stations, and bars throughout Alaska by bush plane, rail, car, and dogsled (a model that’s largely still used today). For two months a year, people place their bets in special red cans that are returned to Nenana in early April. There, teams of locals sort the guesses by hand, entering the tickets into an elaborate analog database that’s checked and cross-checked by myriad workers for accuracy. Even though there are roughly 100 employees working six- or eight-hour shifts, it’s so time consuming that in recent years the contest has been over well before the tickets are all accounted for.

Manager Cherrie Forness has worked for the Ice Classic for 24 years. When she first started, they’d just switched over from typewriters to computer docs to input the then $2 tickets. Other than the 50 cent increase (done to help cover overhead, but keep the game accessible to everyone), nothing has really changed. Nor is change something the Ice Classic is itching for—there are no plans to move to a digital system in the near future.

“The Ice Classic is owned by the people in the community,” Forness says. “It employs people. And they’ve always just wanted to keep it the way it’s been. It’s traditional. This works for us.”

Last year employees sorted through roughly 287,000 tickets. It’s unlikely that contest organizers will know how many were purchased in 2020 until, best case scenario, early summer—they haven’t yet sorted the guesses because of COVID-19 hunker-down orders and as of now, they don’t have a timeline for when winners will be announced.

Beyond employing oodles of locals, the contest is also known for its charitable donations.

Though the Alaska legislature is currently weighing the option of opening the state to more gambling revenue streams, right now the only gaming industry allowed is nonprofit.

The Classic is a hold-over from Alaska’s more Wild West, pre-statehood years. Before becoming the 49th state in 1959, Alaska had a robust gambling culture. Membership in the union changed that. The Alaska Legislature legalized charitable lottery-style games in 1960, largely to allow the Classic to continue (and making it one of the oldest continuously running betting events in the country). Sixteen percent of all ticket sales are used for scholarship programs, local causes, and sporting groups, and a handful of larger medical charities. Last year the Ice Classic was able to donate $90,000.

The Ice Classic isn’t just a little lottery in Alaska. It serves a globally important purpose. Data generated from the tripod’s history has come to be an invaluable source of climate data for scientists.

“The Nenana Ice Classic is a unique climate record in Alaska in that break-up has been determined at the same place, in the same weird way, in a town that is almost the same population for 100 years,” says Rick Thoman, a climate specialist at University of Alaska Fairbanks. “Ice thickness measurements have been made for a much shorter period of time and are much more difficult to do because thickness typically varies significantly over short distances.”

With so few variables (the single channel river has never been dammed and the town is remote), Thoman says, despite its quirkiness, it’s highly accurate, even after 104 years.

Thoman recently co-authored a study produced by the International Arctic Research Center, titled “Alaska’s Changing Environment: Documenting Alaska’s physical and biological changes through observations,” that referenced the fact that the break-up is trending earlier.

The report states: “Four of the past six years have seen break-up earlier than all but one year prior to 1990. The earliest break-up in the history of the Nenana Ice Classic, by six days, was in 2019.”

In the weeks leading up to the tripod’s polar plunge, Ice Classic enthusiast Rebecca Troxel did daily live streams on a Facebook fan page to talk about ice thickness at various points along the river. In the comments, locals beseeched the tripod to pull a Humpty Dumpty and come tumbling down near their betting time.

In the final days of the contest, Troxel spent much of her day hanging out by the side of the river, watching for changes.

“This is amazing,” she gushed on one of her many live streams as a few sizable chunks of ice broke loose from the bottom of the river and breeched like whales. “This never gets old.”

Troxel says her favorite break-up was the first one she witnessed.

“You could feel it and hear it, as all the ice was churning down the river,” Troxel says. “It’s like a thunderstorm, huge and uncontrollable, just groaning and rumbling as the ice is hitting each other. It’s around you and consuming you. That started my love for this.”

Troxel isn’t alone in her zeal for ice melt. She says at any given time there’s roughly 20 other groups of people watching and waiting (this year mostly from the safety of their cars). In the days leading up to the finish, the number was more than double.

Dylan Hooper lives 10 hours away from Nenana on the Kenai Peninsula, so he was unable to watch in person, but sporadically watched the live stream. He had a lot of money riding on this year’s contest. For the past three years, he’s organized a pool of bets, though this year, it’s just him and his brother chipping in on upwards of 1,000 tickets.

“I try to make a prediction of the most likely day it’ll go out,” Hooper says. “I got the idea from a friend who teaches statistics and I’ve done some math modeling with the data available. I dug into the data and started seeing some patterns that might tell us something.”

Hooper says they’ll identify the most likely day and purchase a swath of tickets for that day and a few days on either side of it. Hooper said it’s such a nerve-wracking time in his household that his wife has since put a moratorium on talking about it in her presence.

“It’s stressful watching things unfold,” Hooper says. “Last year I spent a lot of time staring at the live feed. There’s nothing you can do about it, though.”

His first year betting, Nenana saw a late cold snap and their guesses were way off. Last year they’d chosen the right day, but the ice gave way in the middle of the night—a time that was statistically unlikely—and the bulk of their guesses were midday.

This year, though, the clock stopped on April 27 at 12:56 p.m. (Alaska Standard Time). One of Hooper’s guesses was spot on. He’s won, but will likely have to wait until mid-summer to know if he was the only one with the correct time.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook