Celebrating Abby Fisher, One of the First African-American Cookbook Authors

Chefs are recreating pickled foods she made as an ex-slave turned successful chef.

One summer day in 1880, a 48-year-old Mrs. Abby Fisher took the stage at the 15th annual San Francisco Mechanics’ Institute Fair to accept two medals: a bronze for best pickles and sauces, and a silver for best assortment of jellies and preserves. The jurors later wrote that “her pickles and sauces have a piquancy and flavor seldom equaled, and, when once tasted, not soon forgotten.”

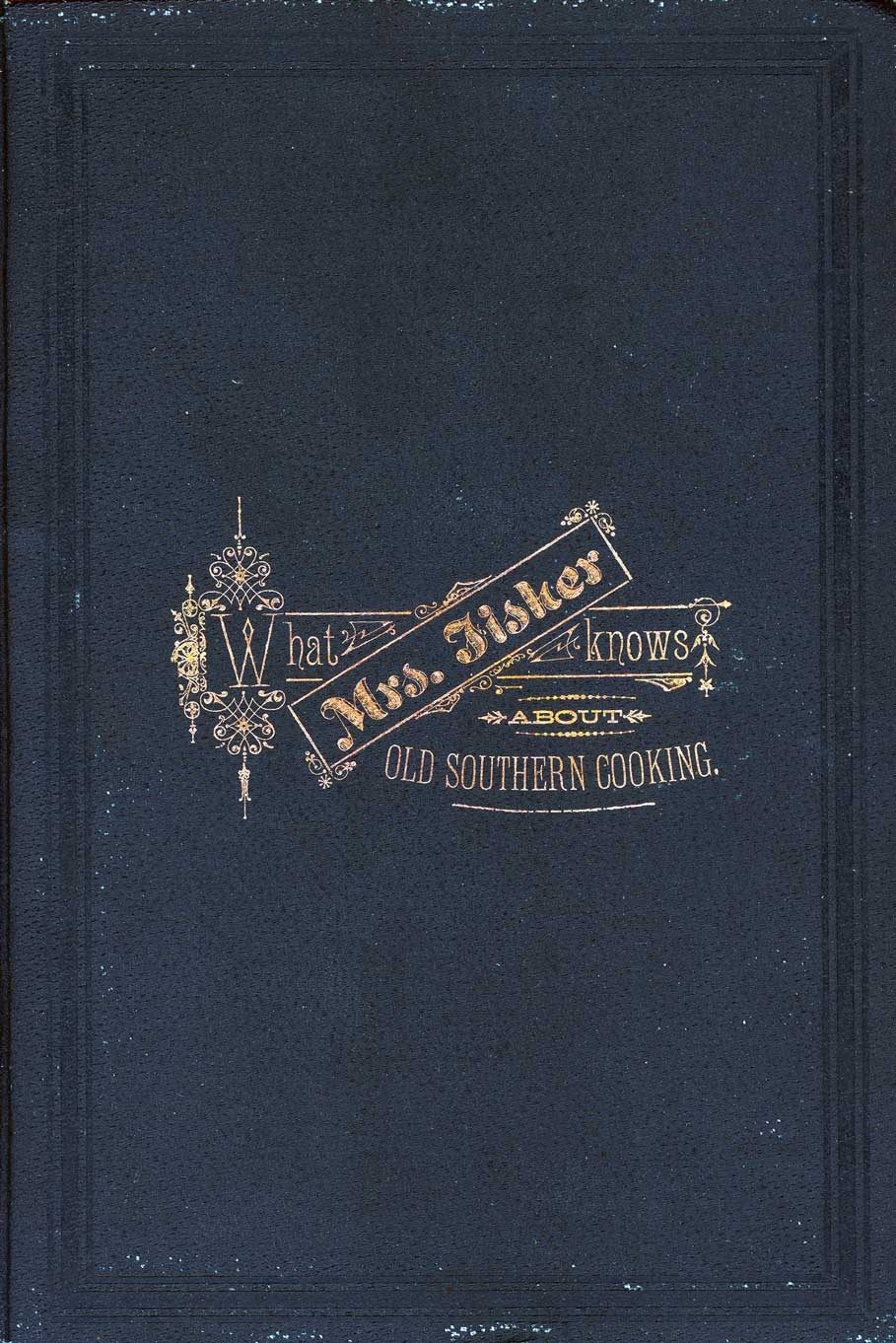

At this point, Fisher was already a famed, local, culinary authority. She had taken home a diploma at the Sacramento State Fair in 1879, its highest award. Her cooking chops became so revered that the Women’s Co-operative Printing Office published her extensive cookbook, entitled What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking, in 1881.

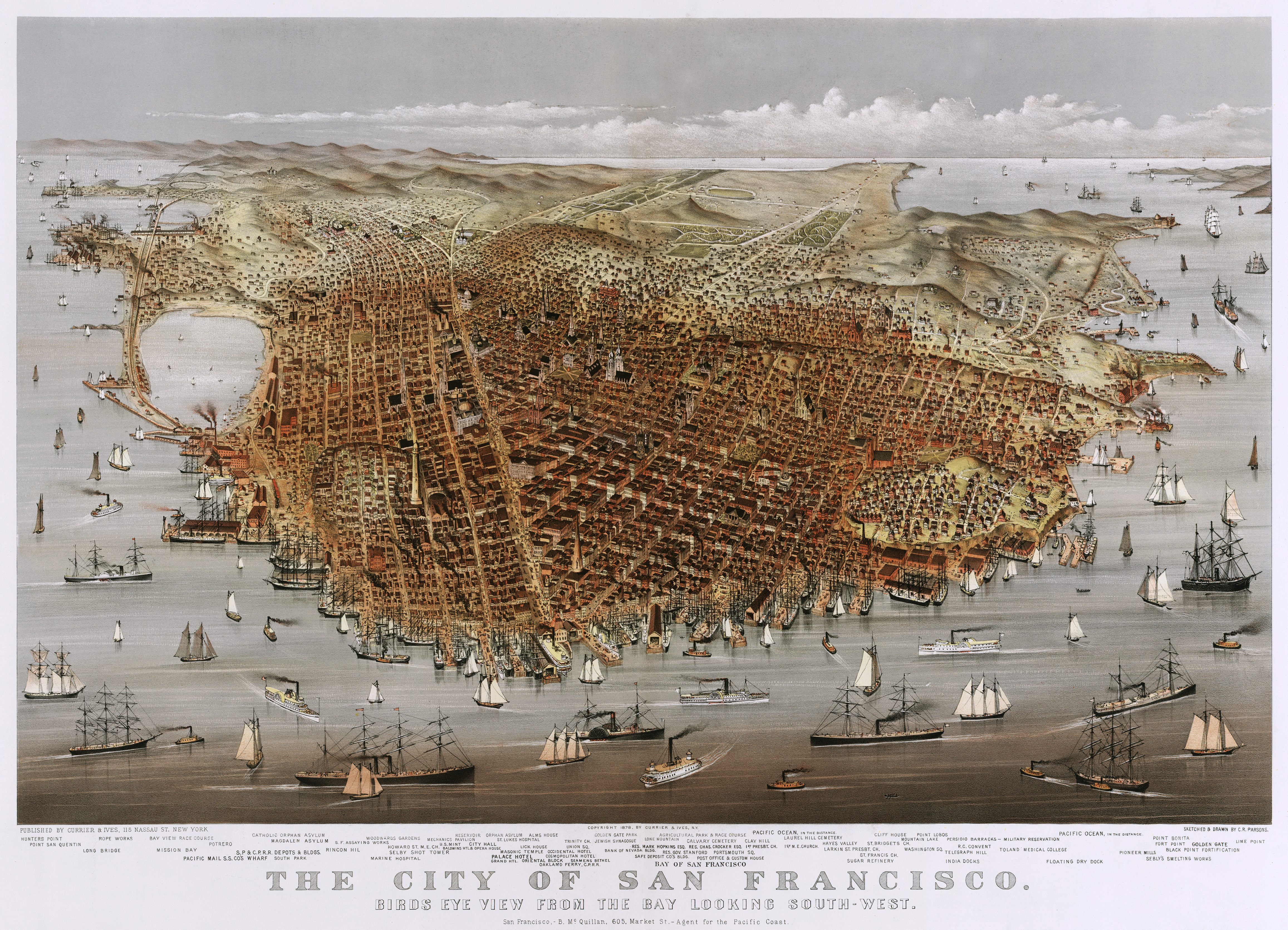

Yet Fisher’s feats went far beyond ribbons and state fairs. Fisher had migrated from Mobile, Alabama, with her husband, Alexander, and 11 children to California in 1877. Upon arriving in San Francisco, she used her talents to set up a preserves business along with her husband. And while the 1880 city census notes his profession as “pickle and preserves manufacturer,” the business was under her name, “Mrs. Abby Fisher & Co.”

The extraordinary cookbook she put together is one of the first authored by an African-American woman, along with Malinda Russell’s 1866 treatise A Domestic Cook Book. Besides being a trove for sensational recipes that stand the test of time—ranging from savory to sweet, encompassing both the briney and beefy—Fisher’s cookbook also helped to immortalize the culinary imprint of African-Americans. “She was clearly a remarkably resourceful woman, one of those strong matriarchal types who kept their families together under the most adverse circumstances,” writes food historian Karen Hess in her afterword of What Mrs. Fisher Knows About Old Southern Cooking.

What’s most remarkable about Fisher’s recipes is that they’re captured in her own words—a rarity for a former slave. They also provide a clear glimpse into food that she herself made at home for her family—not just what she might have cooked at plantations. While being especially adept at making pickles and preserves, as well as cooking for large quantities of people, she also provided recipes for the likes of blackberry syrup, which she calls an “old Southern plantation home remedy among colored people.” Within the book’s final recipe, “pap for infant diet,” she shares the most personal endorsement of all: “I have given birth to eleven children and raised them all, and nursed them with this diet.”

Given that historians know little about Fisher’s upbringing, this seminal part of the Southern American food canon provides a key window into her life. We know, for instance, that Fisher had “upwards of thirty-five years” of experience cooking, thanks to what she mentions in the book’s preface. But her recipes also denote transgressions and surprising influences. Fisher was born to a South Carolinian mother and a French father, yet she carefully notes to “never stir rice while boiling” in her “Ochra Gumbo” recipe. This suggests a move away from what Hess calls the “Carolina method” of cooking rice.

Fisher states in her cookbook’s introduction that she was not “able to read or write” herself, so she relied on dictation to piece together the book. While Fisher’s cooking was revered by her (presumably wealthy) “lady friends and patrons” in the Bay Area, who frequently asked her to immortalize her recipes, the book didn’t receive a wide circulation. Copies, and knowledge of Fisher’s cooking, remained relatively scarce until the 1980s, when one went up for auction at Sotheby’s. It caught the eye of Karen Hess, the late Southern cooking historian. In 1995, Applewood Books reprinted Mrs. Fisher’s cookbook (the publisher claims that prior to their reprinting, only 100 copies existed). Its popularity began to surge from there. Nearly a decade later, Michigan State University archived the book as a central work of American cookery in their Feeding America: The Historic American Cookbook Project.

In recent years, chefs and cultural institutions alike have been cooking Fisher’s specialties and revamping them for 21st-century palates. (Lard isn’t as popular as it used to be.) In 2014, Amanda Moniz, the David M. Rubenstein Curator of Philanthropy at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, who also teaches historic cooking classes, wrote about recreating Fisher’s fare. She crafted a meal that honors early African-American cookbook authors, including Fisher, and made a version of her chow chow, a pickled relish. She followed it to the letter, but cut down on the vast quantities of cucumber and vinegar, and let the cabbage sit for four hours in salt instead of twelve.

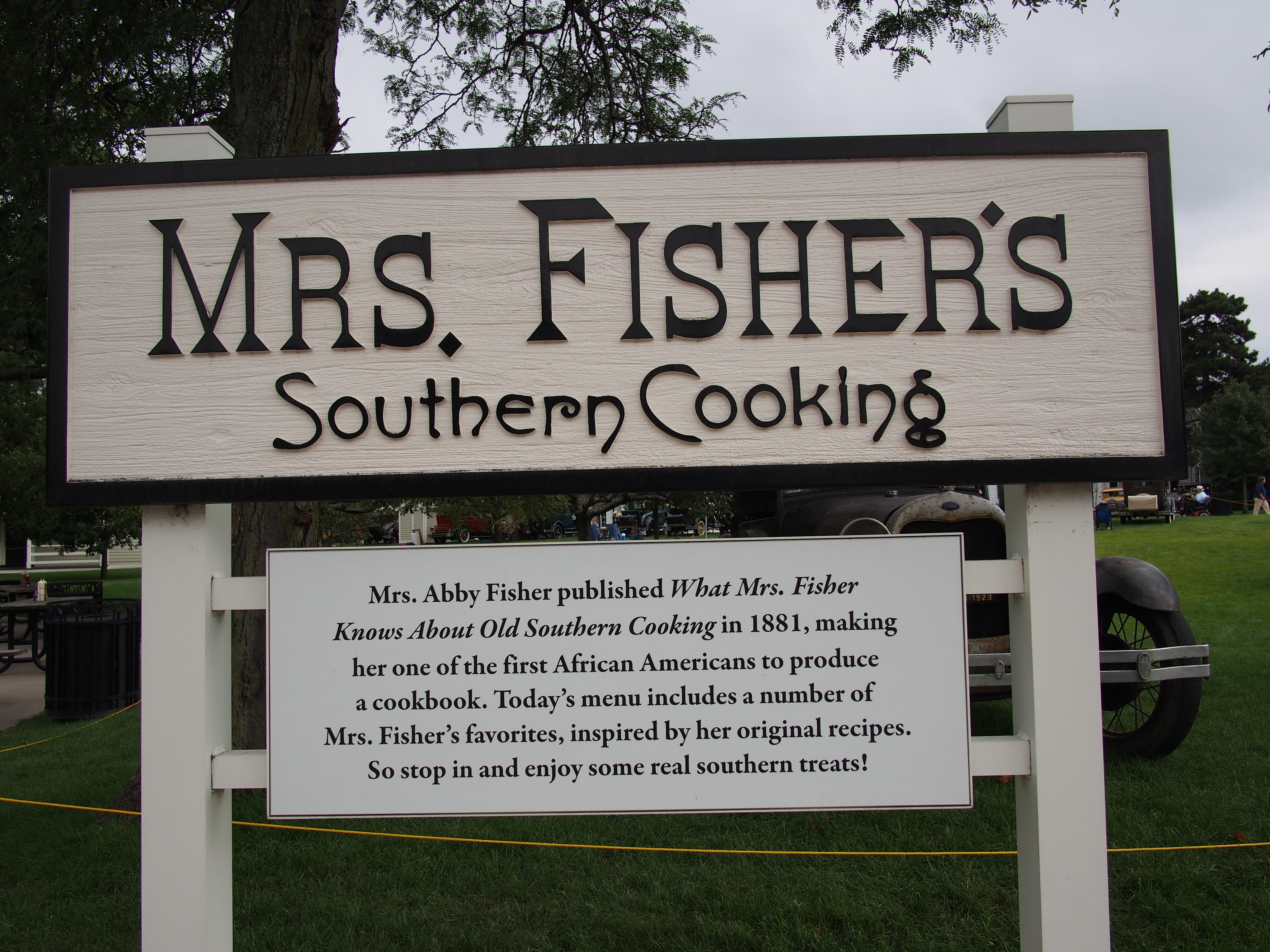

The Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation in Dearborn, Michigan, has also been revitalizing Fisher’s recipes, in an effort to give visitors a taste of history. Lee Ward, the museum’s Director of Catering and Food Services, and his team recreated some of Fisher’s recipes available on-site at the “Mrs. Fisher’s” stand. Ward collaborated with Jeanine Head Miller, the museum’s Curator of Domestic Life, to pick from Fisher’s cadre of recipes. Collectively, they pored over Fisher’s cookbook and selected recipes that played towards particular culinary strengths (think brandied peaches on top of ice cream). Others, such as the shrimp salad with sweet pickles, also help illustrate her life’s story to visitors.

Fisher suggests in her book that friends and patrons alike encouraged her to keep a written record of her recipes. Still, it’s clear that Fisher found educating future generations about the culinary traditions she mastered in life crucial: “The book will be found a complete instructor, so that a child can understand it and learn the art of cooking,” she explains in the preface. The fact that Fisher dictated these recipes at all speaks towards a larger goal of preservation, too, for a pivotal American culinary tradition borne out of much strife.

“The art of Southern cooking was created by the thousands of African-American women who cooked in the wealthy households of the South, as well as cooking for their own families,” Miller says. “So no one person has created that art. But what’s wonderful about Mrs. Fisher’s [books] is that it preserves—in her own words, and in her own recipes—some very sophisticated versions of those foodways.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook