A Lawn Day’s Journey from Scythes and Donkeys to Power Mowers

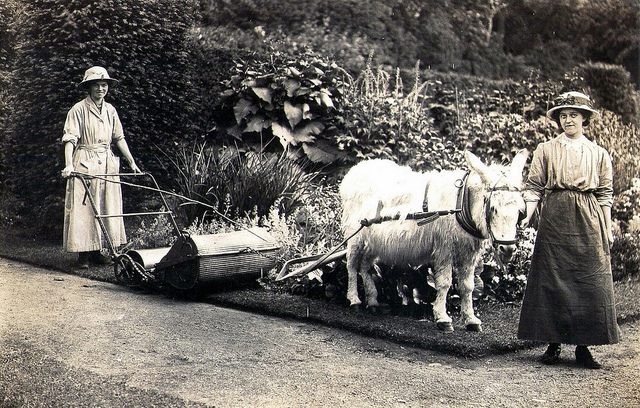

A donkey-drawn lawn mower. (Photo: Paul Townsend/flickr)

A version of this post originally appeared on the Tedium newsletter.

The recent drought that has gripped the state of California—and kept a lot of lawns looking parched in the process—serves as a great opportunity to look back on the roots of lawn care.

A well-kept green lawn, whether intentionally or not, expresses a certain economic status–one that is being challenged in the Sunshine State due to a glut of sun and a lack of water. Stories of celebrities or residents of wealthy communities attempting to flout water restrictions for the sake of their grass are common.

But if lawns end up separating the haves and have-nots, it wouldn’t really be anything new. The mower, a relatively new invention, put grass-cutting within reach of average homeowners.

Before that, maintaining a lawn was a game for the elites.

The Parterre du Nord at the Gardens of Versailles. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

The Parterre du Nord at the Gardens of Versailles. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

For generations, we’ve heard chatter that machines were eventually going to take over our jobs and make us all broke, poor, and useless, with no reason to work.

But the lawn mower is a reminder of what can happen when a machine democratizes something that was once only available to the upper classes. Within a few decades, fancy lawns went from something only rich people could afford to a standard of suburban life. And the reason for that is the lawn mower.

Lawns with short grass have only been in style for the past few hundred years or so–thanks to members of the French royalty like Louis XIV, who helped sell the rest of the world on the idea. Problem was, tapis vert, or perfectly short grass, was difficult to achieve at first, which meant it was cost-prohibitive for most people.

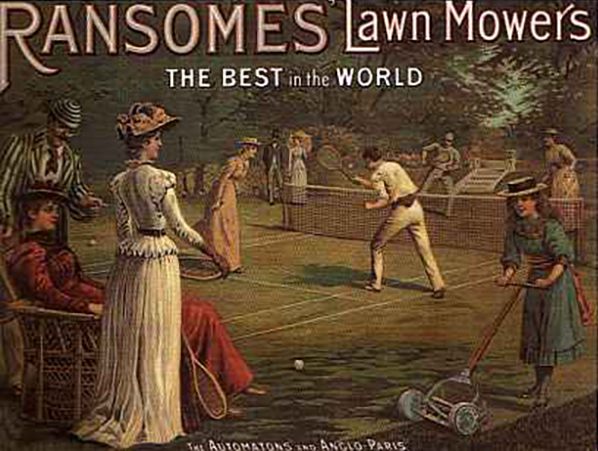

An 1867 advertisement for an ’Automaton’ Ransome’s lawn mower. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

An 1867 advertisement for an ’Automaton’ Ransome’s lawn mower. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Prior to the lawn mower, you needed lots of physical manpower to keep up the fancy look of a well-kept garden, which meant you needed a lot of servants to keep up the look of things. Those who worked on lawns needed tools such as shears and scythes to keep the turf at a reasonable length.

If this sounds like more trouble than it’s worth, you can thank Edwin Beard Budding for saving the day. In 1827, the British engineer came up with the wheel-and-blade machinery behind the modern lawn mower. Budding’s mower, which was invented decades before the gas-powered engines we’re familiar with today, relied on a horizontal cylinder shape.

At first, you could only cut grass by pushing it forward; later, he came up with different sizes, eventually allowing for grass to be cut no matter which way you push the device.

An early commercial lawn mower, 1930. (Photo: Bundesarchiv/WikiCommons CC-BY-SA)

Budding died before his device went mainstream, but eventually it took off, thanks to two key factors: the rise of the suburb, which meant more people had grass to maintain, and the internal combustion engine, which put a little power in those blades and made the job of lawn maintenance even easier.

“It’s amazing that his invention is pretty much unchanged, nobody’s found a better way of doing this than he found in 1830,” David Withers, the president of mower-maker Ransomes Jacobsen, said in April upon putting a plaque on Budding’s original workshop.

Lawnmowers don’t even trump humans in all cases. Simon Danant, a forester and an expert at living off the grid, has mastered scythe usage for lawn care. In a competition with a riding mower, Danant and his scythe actually cut a grassy plot faster than the modern machine.

Soon enough though, we’ll likely be able to maintain our lawns with robots. But perhaps it’s not worth following the technology to its logical conclusion. Perhaps we care too much about these plots of grass that cover our land and force us into a never-ending cycle of maintenance, all for the benefit of some extra property value.

An early cylinder (reel) mower, showing a fixed cutting blade in front of the rear roller and wheel-driven rotary blades. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

An early cylinder (reel) mower, showing a fixed cutting blade in front of the rear roller and wheel-driven rotary blades. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Author Michael Pollan once wrote an essay describing how he grew philosophically opposed to lawn care, and you sort of feel for the blades of grass by the end of it.

“Mowing the lawn, I felt like I was battling the earth rather than working it; each week it sent forth a green army and each week I beat it back with my infernal machine,” he wrote back in 1989. “Unlike every other plant in my garden, the grasses were anonymous, massified, deprived of any change or development whatsoever, not to mention any semblance of self-determination. I ruled a totalitarian landscape.”

Pollan has a point: In a world where complexity and diversity of plant life is often treasured, why are we so obsessed with the clean perfection of a yard where every blade is in its correct place?

(Photo: TunedIn by Westend61/shutterstock.com)

(Photo: TunedIn by Westend61/shutterstock.com)

The Atlantic’s Megan Garber, in a recent piece on this topic, suggested that lawns have become more important as an icon of something attainable by the average person than as sheer decoration.

“To give up our lawns would be, in some sense, to concede a kind of defeat–to nature, to the march of time, to the ecosystemic realities of the new century,” she wrote. “It would require us to do something Americans have not traditionally been very good at: acknowledging our own limitations.”

Maybe she’s right, and the weather is certainly helping make the argument in a bunch of western states. Perhaps Mother Nature is trying—with her dry, parched, overbearing sense of humor—to drop a hint: If you’re so obsessed with green carpet, buy astroturf.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook