When American Feminists Were Pilloried for Daring to Wear Bloomers

Turns out that there is no garment that women can’t get criticized for wearing.

An engraving of four women wearing different types of bloomers, c. 1850. (Photo: Kean Collection/Getty Images)

In the summer of 1851, a pair of pants made headlines across America.

The “bloomer costume,” also called “Turkish trowsers,” set off a storm of commentary from women’s rights activists, fashion enthusiasts, and critics across the country. In an August issue of the Water-Cure Journal, a publication dedicated to alternative medicine and social reform, a woman named Mary Williams described the outfit as “Turkish pantaloons and a short skirt, leaving the upper vestments to be fashioned according to the taste of the wearer.” Williams wrote that the bloomer costume was “infinitely superior” and “ought to receive the friendly countenance of all sensible persons of either sex,” emphasizing that the choice to wear the outfit was based on health and fashion, rather than a desire to wear men’s clothes.

Many historians point to social reformer Elizabeth Smith Miller as the first American to wear the bloomer costume, and Mrs. Miller’s cousin Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and other prominent women’s rights activists of the time did adopt the pants for their public engagements after their stateside debut. But the outfit became most closely associated with Amelia Jenks Bloomer, a women’s rights activist and editor of The Lily, a temperance journal. She was an outspoken proponent of the style, writing about it in The Lily and wearing bloomers to events and rallies. The “bloomer costume” caught on among some white middle-class women who saw “dress reform” as an integral part of the fight for women’s equality in the mid-1800s. Some 50 years before bloomer-clad women rode bicycles in public, heralding a new era of freedom for women, few dared to don the trousers in public. The women who did wear the style became known as Bloomers, partly for their dress and partly for their interest in women’s rights issues.

The bloomer trend may have been short-lived in 1851 but the media storm that followed made it clear that, especially for women, fashion is political, whether we like it or not.

Amelia Bloomer, c. 1860. (Photo: Public Domain)

Bloomers were initially reported on as an intriguing fad (“The Bloomers were out yesterday in force,” crowed the New York Tribune in June 1851 under the headline “The New Female Costume”) and a pop culture curiosity, popping up in plays, music, and art. But as more women’s rights activists began to adopt the garment and women across the country began making their own bloomers and dictating their own fashion choices in the process, the pants appeared to be more of a threat than a trend. Many people (most of them men) were convinced that bloomers were a political statement instead of a health initiative—writers stoked fears of a women’s takeover of male space, led by Bloomers in “Turkish trowsers.”

The women who wore them were quickly characterized as independent, exotic, and unpredictable. A New York Times editorial in October 1851 warned readers that for women’s rights activists, “there is an obvious tendency to encroach upon masculine manners, manifested even in trifles, which cannot be too severely rebuked or too speedily repressed.” These “masculine manners” included wearing bloomers, deemed to be too close to men’s garments for men’s comfort. Bloomers (the women and the pants) were derided in magazines like Harper’s Monthly Magazine and London-based Punch. In a Punch cartoon reprinted in Harper’s in August 1851 (one of many in the ensuing years), a Bloomer proudly stands in the middle of a roomful of men, her short skirt displaying the radical pants below.

Bloomers worn by a basketball team, c. 1905. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-hec-20627)

The accompanying article, also taken from Punch, was a parody letter to the editor by a feminist named “Theodosia E. Bang.” The fake Theodosia declared “we are emancipating ourselves, among other badges of the slavery of feudalism, from the inconvenient dress of the European female. With man’s functions, we have asserted our right to his garb, and especially to that part of it which invests the lower extremities.” The letter goes on to say that the American woman would next begin to wear men’s hats and jackets in their pursuit of power. Although played for laughs, the fake letter underscored real fears of women’s increasing presence in public life.

A Punch cartoon from 1851 showing women in bloomers smoking, which was deemed unsuitable for women in Victorian society. (Photo: Public Domain)

The negative responses to the bloomer costume weren’t confined to print alone. In July 1851, the New York Tribune ran a city item describing a “beautiful Bloomer” worn by a young woman, taking care to note that “so far as we saw no impertinent staring was offered,” implying that staring and commenting were a normal response to the clothing. On a darker note, a London correspondent for the Times reported in November 1851 that women in bloomers are “rarely seen in the streets, one reason being that the unlucky wearer of Bloomer attire has an excellent chance of being mobbed for her temerity.” Even two years later, many women were still nervous about wearing bloomers. “I stand alone in this place,” Sarah Selby wrote in The Water-Cure Journal in June 1853, “no one besides myself having dared to meet public scorn in this glorious enterprise.”

In many of these instances, the pants and the women wearing them were one in the same, representing a new kind of woman whose newfangled clothing was connected to a shift in public behavior. In her history of women in pants at The Toast, Kathleen Cooper writes: “In the language of clothes, pants equal power,” underscoring the social fears and possibilities that emerge when women make their own clothing choices.

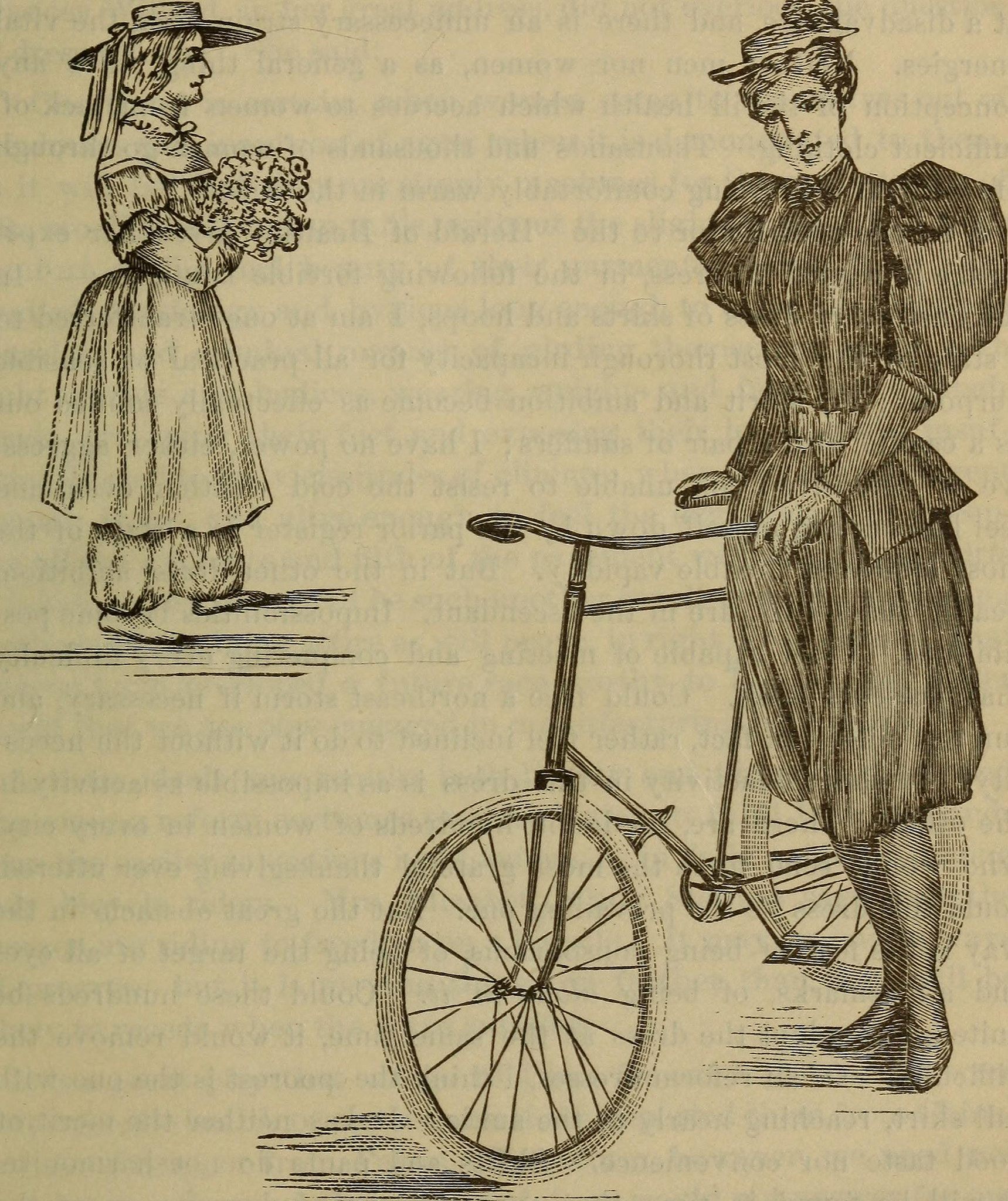

A woman in bloomers with a bicycle, 1896. (Photo: Internet Archive/Public Domain)

Amid the seemingly endless mockery during 1851 and for a few years afterward, the most public figures in the women’s rights movement decided to abandon the dress for their public speeches and events, including Amelia Jenks Bloomer herself.

The choice that some women made to stop wearing bloomers caused rifts among activists and their supporters; some felt that dress reform was required for full equality, while others saw it as secondary to issues of property ownership and voting. In The Radical Women’s Press of the 1850s, Ann Russo and Cheris Kramarae include a letter from activist Lucy Stone to the Sibyl magazine in 1857 that reads: “I frankly confess that I do not expect any speedy or widespread change in the dress of women until as a body they feel a deeper disconnect with their present entire position.”

A woman in bloomers defying the “no smoking” sign, c. 1897. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-56425)

In the ultimate gesture of the personal being political, Jenks Bloomer commented at some length about her feelings on the garment. She said that she wore them for comfort, noting the societal pressure to revert to long skirts, and declared that Elizabeth Cady Stanton ultimately stopped wearing bloomers because of pushback from the men in her family. Ironically, by the turn of the 20th century, bloomers had become associated with bicycles, offering some women the independence and freedom of movement advocated by dress reformers a half-century earlier.

But even with the widespread popularity of pants for women over the past century, they still make headlines today: Hillary Clinton will forever be associated with pantsuits, school dress codes forbid teen girls from wearing leggings as pants, and the Hollywood Reporter spent three paragraphs detailing late-night host Samantha Bee’s pants-based wardrobe in a recent profile. Women wearing pants remain a cultural lightning rod, representing the possibilities that might arise if they have the power to control their own bodies without criticism.

Recalling the bloomer fad in a collected volume of her works edited and published by her husband Dexter in 1895, Jenks Bloomer apparently didn’t see it that way. “In the minds of some people, the short dress and women’s rights were inseparably connected,” she wrote. “With us, the dress was but an incident, and we were not willing to sacrifice greater questions to it.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook