How Pants Went From Banned to Required in the Roman Empire

Six hundred years in the history of trousers.

Go to a meeting with any male politician today and you’re almost certainly going to be standing in front of a man wearing pants, except perhaps in Bermuda, where the eponymous shorts are the nation’s official dress. But in Imperial Rome, obviously, things were a little different—no man of honor would think of wearing what was considered the garb of a savage barbarian.

When Marcus Tullius Cicero, an eloquent orator and lawyer, was defending the former Gaul governor Fonteius from accusations of extortion, he cited the wearing of pants as a sign of the “innate aggressiveness” of the Gauls—and an extenuating circumstance for his client:

Are you then hesitating, O judges, when all these nations have an innate hatred to and wage incessant war with the name of the Roman people? Do you think that, with their military cloaks and their breeches, they come to us in a lowly and submissive spirit, as these do (…)? Nothing is further from the truth.

Think of it as the “Trouser Defense.”

“Good orators were using rhetoric in a rather sophisticated way—they were picturing foreign tribes in the way that mostly suited their needs, from fierce aggressors to backwards folks and they were relying on visual imageries to make sure that ‘barbarian otherness’ would stand out,” says Susanne Elm, a historian from the University of California, Berkeley, who studies Rome’s relationship with the tribes to the north, which they collectively referred to as “barbarians.” The breeches were, in this case, a powerful symbol of “otherness.”

Cicero was not alone in relating pants to a primordial, uncivilized life. In 9 A.D. Ovid, by then an acclaimed poet, was exiled by Emperor Augustus, for reasons that remain unclear (but may have had to do with Augustus’s niece). In what is now Tomis, Romania, the poet first encountered barbarians: “The people even when they were not dangerous, were odious, clothed in skins and trousers with only their faces visible.”

There were no particular hygienic reasons for the Roman distaste for pants, says Professor Kelly Olson, author of “Masculinity and Dress in Roman Antiquity.” They did not like them, it appears, because of their association with non-Romans.

But opinions change with time, and not long after, the historian and senator Publius Cornelius Tacitus listed pants among a range of “exotic” behaviors of Germanic tribes, whom he praised for having morals unweakened by civilization: river-bathing, ponytails (“wisted tufts resembling horns or plumes”), and pants.

It is not as though every person walking around ancient Rome was wearing a toga—they were more like formal wear. Tunics where the most common garment, sleeveless or short-sleeved for men, and long-sleeved, ankle-length for women. Squeezing one’s legs into stitched fabric was simply not tradition, and not generally demanded by the Mediterranean climate.

However, as the empire expanded, this began to change. Romans and tribes from newly annexed northern lands fought side-by-side to protect their borders from still other barbarians, such as the Visigoths. So military trousers used by Germans or Gauls became the outfit of choice for Roman troops—presumably because they’re more practical on a northern battlefield than flappy tunics.

Evidence of this early trouserization of Roman troops can be seen in the spiral bas-relief of Trajan’s Column, the 98-foot-tall, 12-foot-thick marble monument erected in 113 to honor the emperor’s triumph over the Dacians, pants-wearers from what is now Romania and the region around it. In that depiction, generals and other high-rank figures wear tunics or togas, while common soldiers wear leggings.

Like with GPS and the internet, innovations from the military sector slowly spread to civil society. By 397, trousers, in all their odiousness, were becoming so common that brother-emperors Honorius and Arcadius (of the Western and Eastern empires, respectively) issued an official trouser ban. The ban is cited in a code named for their father, Theodosianus, which read: “Within the venerable City no person should be allowed to appropriate to himself the use of boots or trousers. But if any man should attempt to contravene this sanction, We command that in accordance with the sentence of the Illustrious Prefect, the offender shall be stripped of all his resources and delivered into perpetual exile.”

“What the ban basically does is that it bans civilians from wearing a military outfit in the capital,” says Elm, “so one could see it as an indirect way to make it easy to distinguish civilians from military men at a time where tension was high.” Four years prior, Emperor Valens had been killed in battle within Roman borders, and a third of the army had been wiped out. So banning trousers could have been a way to make sure that the capital was easier to police, and that fighters were kept out.

The ban could also be read as the desperate attempt of late-period emperors to cling to a sense of Roman identity at a time where the empire had become a melting pot of traditions, after hundreds of years of expansion and cultural appropriation. Long hair and flashy jewels soon joined boots and pants as forbidden fashion.

“Barbarian influence on fashion was something that emperors wanted to control, but then their own bodyguards, which presumably they trusted, were barbarians,” says Elm. “So rather than anti-barbarian, they were mostly anti-barbarian-identity.” Restoring concepts such as “purity” and “identity” is not uncommon in fading empires—authoritarian ways to make rulers feel in control at home in the face of external weakness.

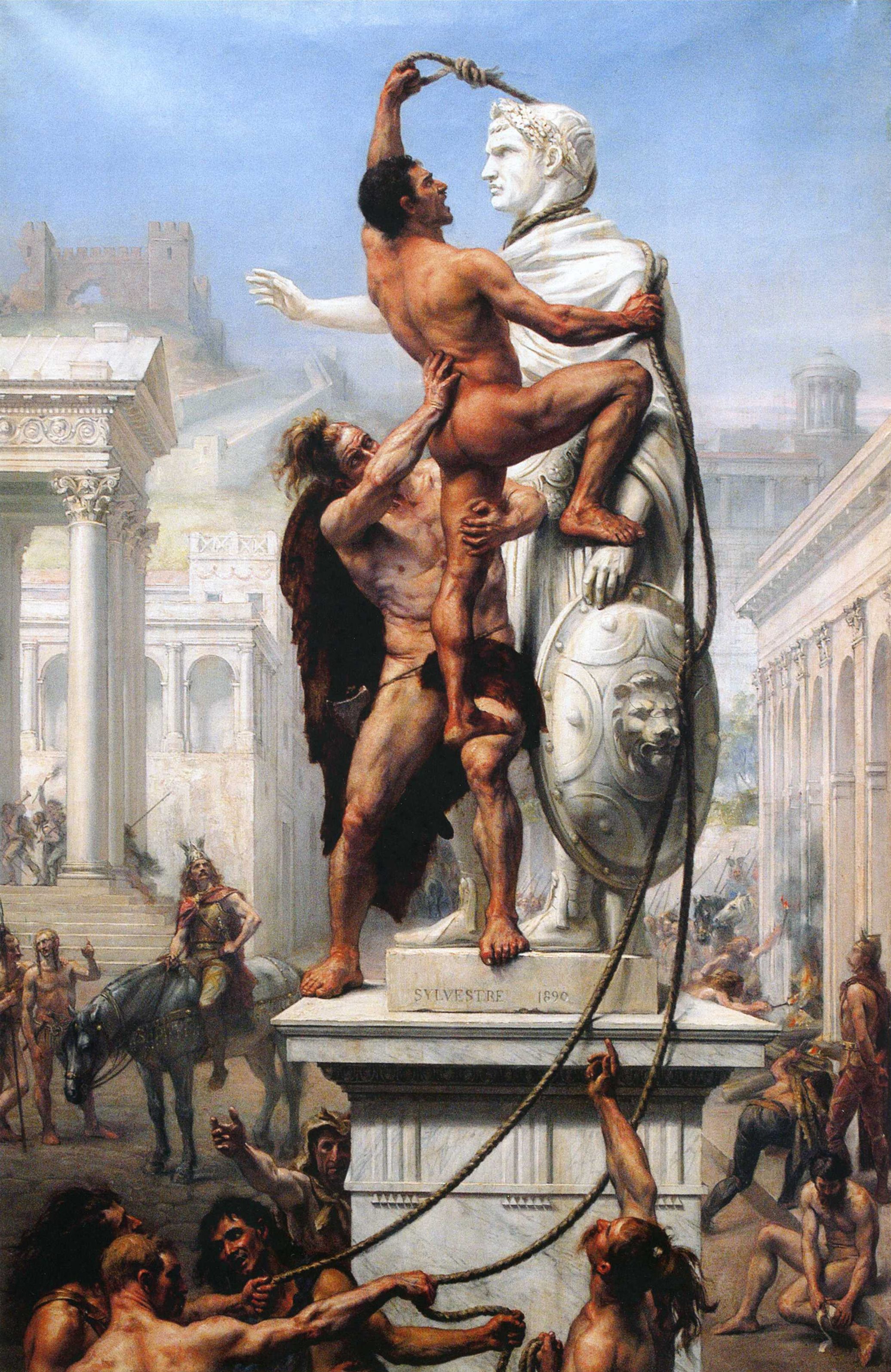

It’s not clear whether the trouser ban had any impact on Roman identity, or was even actually enforced. There is no legal evidence or angry letters. But 13 years after the ban, Visigoth fighters led by King Alaric violently marched into and sacked Rome, an event that most historians consider a critical shove in the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476. The ban was more or less rendered moot.

Of course, pants won in the end. By a century later, the barbarians had claimed the battle for the sartorial soul of the court of Constantinople, the only Roman court left. “By the fifth and sixth centuries, suddenly the so-called barbarian custom, sleeved top and trousers, had become the official uniform of the Roman court. If you were close to the emperor, that’s what you would wear.” says Olson. “Scholars have not yet been able to explain how that happened, trousers going from being banned to be legally required clothes for the Roman court.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook