At Tom Thumb Weddings, Children Get Faux-Married to Each Other

The tradition began with the real Mr. Thumb, a short-statured performer in P.T. Barnum’s circus.

Featuring fancy dress, generous parties and disturbingly age-appropriate vows, “Tom Thumb weddings” are oddly anachronistic plays in which young children pretend to marry each other. These plays (not unlike the fake wedding George-Michael and Maeby put on to entertain Alzheimer’s patients in Arrested Development) have been put on for community crowds in America for more than a hundred years, and are still performed today in a manner largely unchanged from their 19th-century origins.

The ritual takes its name and inspiration from Charles Stratton, aka General Tom Thumb, a Connecticut-born man with dwarfism who made his considerable fame in P.T. Barnum’s employ and who in February 1863 married Lavinia Warren, a fellow little person, in a posh New York ceremony nicknamed the “Fairy Wedding.”

Stratton was a gifted performer who could sing, dance, perform a riotous pantsless routine in which he impersonated Grecian statues, and command the fancy of women the world over, to whom he swore he was a general in “Cupid’s artillery.” His biographer estimates that over four decades of fame, Stratton performed for more than 50 million people in two dozen countries. Even Queen Victoria adored him.

Enthusiasm and curiosity swamped criticism of the wedding as a commercialized sideshow, and the Fairy Wedding was a sensation, knocking Civil War news off the New York Times’ front page for three days straight.

There was a miniature silver horse and chariot from Tiffany & Co. as a wedding gift; President Lincoln received the couple afterwards; and the New York Times remarked:

“Those who did and those who did not attend the wedding of Gen. Thomas Thumb and Queen LAVINIA WARREN composed the population of this great Metropolis yesterday, and thenceforth religious and civil parties sink into comparative insignificance before this one arbitrating query of fate—Did you or did you not see Tom Thumb married?”

And indeed, Tom Thumb’s extraordinary wedding would be his lasting legacy, though certainly not in the way he or anyone else would have expected. Stratton died in 1883, and the idea of a theatrical child-wedding as his oddball memorial appeared not long after, taking root particularly in churches and community organizations during the 1890s.

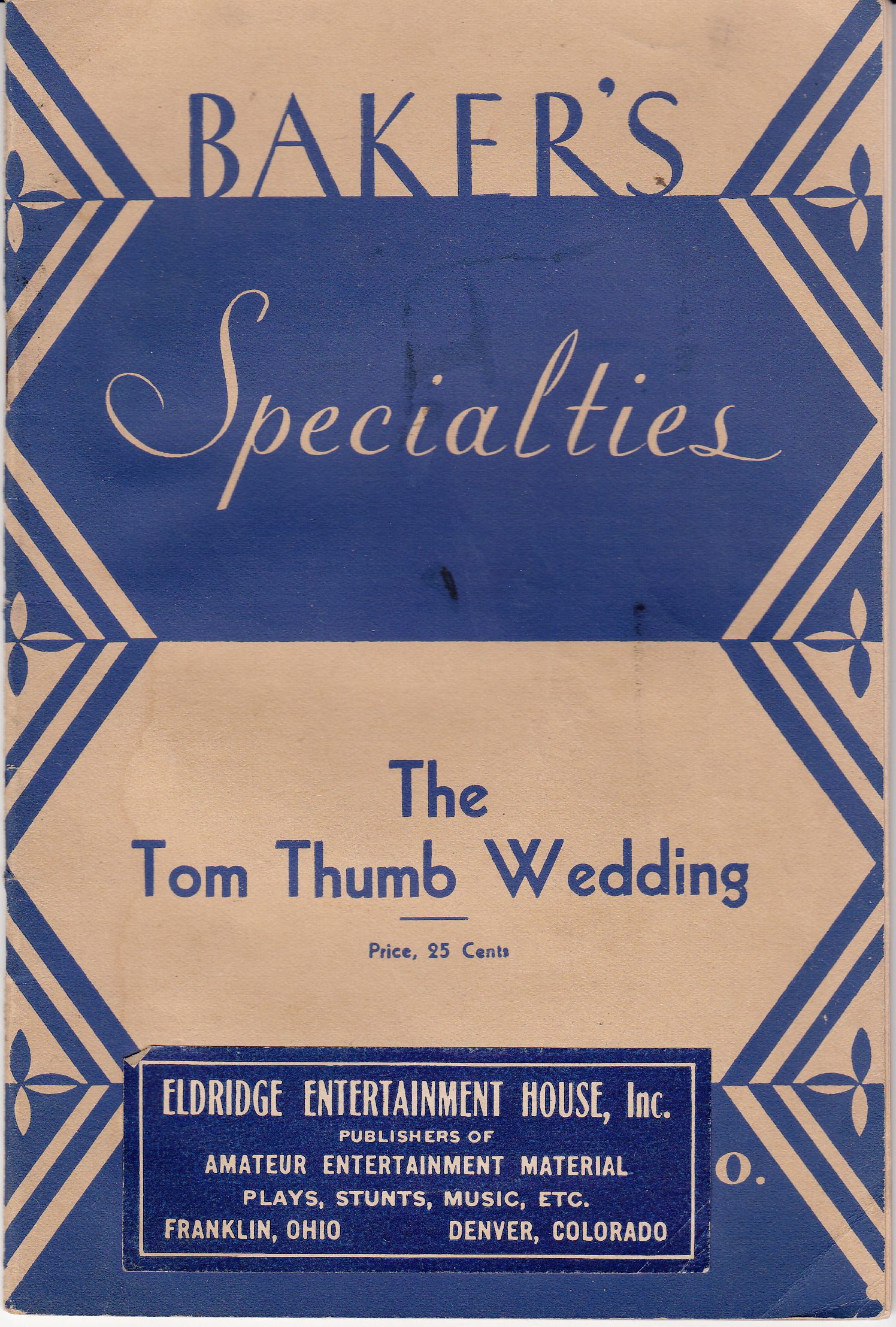

In 1898, the tradition had enough purchase that the Walter H. Baker Company printed a small pamphlet as a do-it-yourself guide to the definitive Tom Thumb Wedding. (Claiming 1898 copyright, the publishers scoff at such rank imitations as “The Marriage of the Tots,” “The Jennie June Wedding,” and “The Marriage of the Midgets.”)

The play envisions a full retinue of wedding participants, with as many as 40 or 50 children recommended for a successful performance: a minister, bride and groom, maid of honor, groomsman, wedding party, ushers, flower-girls, and guests, all well-rehearsed and dressed in their best evening wear.

In Baker’s script the young bride and groom are referred to as “Tom Thumb” and “Jennie June”–an allusion to Stratton’s character and an uncomfortable erasure of Warren’s, which does not bode well for the feminist character of the overall ceremony. And indeed, the vows are as wearisome as you might think: bad marriage jokes for the benefit of the grown-ups, punctuated with tired stereotypes about progressive womanhood and the old ball-and-chain.

Tom takes Jennie, harridan princess: “for better, but not worse, for richer, but not poorer, so long as your cooking does not give me the dyspepsia, and my mother-in-law does not visit oftener than once in a quarter.” (Millinery budget is to be covered by the bride’s father, “out of gratitude for not having you left upon his hands in the deplorable station of a helpless spinster.”)

Jennie takes Tom, eye-rolling Honeymooner, “provided that you do not smoke or drink; provided that you will never mention how your mother used to cook, or sew on buttons, or make your shirt-bosoms shine; provided that you carry up coal three times a day, put out the ashes once a week, bring up the tub, and put up and take down the clothes-line on wash-day, and perform faithfully all other duties demanded by a ‘new woman’ of the nineteenth century.”

At this the pair is pronounced married, and everyone bows and recesses.

Baker & Co.’s copyright warnings aside, the pageants were wildly popular. In smaller communities, a Tom Thumb wedding was often the only show in town; at events like the annual “baby parade” at Asbury Park, New Jersey, they could draw crowds in the thousands.

Commentary and history suggest that the dramatic practice of Tom Thumb weddings began, and grew, in order to teach children about religious or moral values; to model adult conduct and institutions; to offer entertainment and community fundraising potential; and because there was no Netflix to binge. Over time, the event decorated itself with different bells and whistles: sometimes fairytale or cartoon characters attended, sometimes there was singing; and very often there was an ice cream feast to entice the kids to cooperate.

The Hope Pioneer of North Dakota described a 1914 Tom Thumb wedding to benefit the Hope lodge of Rebekahs (a women’s service organization affiliated with the Odd Fellows). Despite the fact that the bride “got a little drowsy and fell off her lilliputian chair,” and never mind that the participants were very quickly distracted from the script by licking their dessert bowls and hiking their fancy skirts over their shoulders, the adults were surprised and delighted by the whole affair. When all was said and done, the lodge took in $75 (about $1,800 today).

The tradition appears to have quieted down in the wake of World War I; and only popped up in any appreciable media sense again in the 1980s, at which point the jokes modernized even if the concept hadn’t: one Philadelphia “wedding” in 1982 purported to marry three child couples: the Flintstones, the Smurfs and the Jeffersons.

Even today, Tom Thumb’s bizarre, infantilizing legacy continues; though as the practice has continued into the current era, the scripts have revealed what really matters to keep the tradition going: today, vows have been known to negotiate terms not around chores or gender roles so much as snacks, Nintendo, and parental rewards for playing along with the whole notion.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook