The 1880s Supper Club That Loved Bad Luck

How to remove the stigma from the number 13? Through a series of macabre dinner parties, of course.

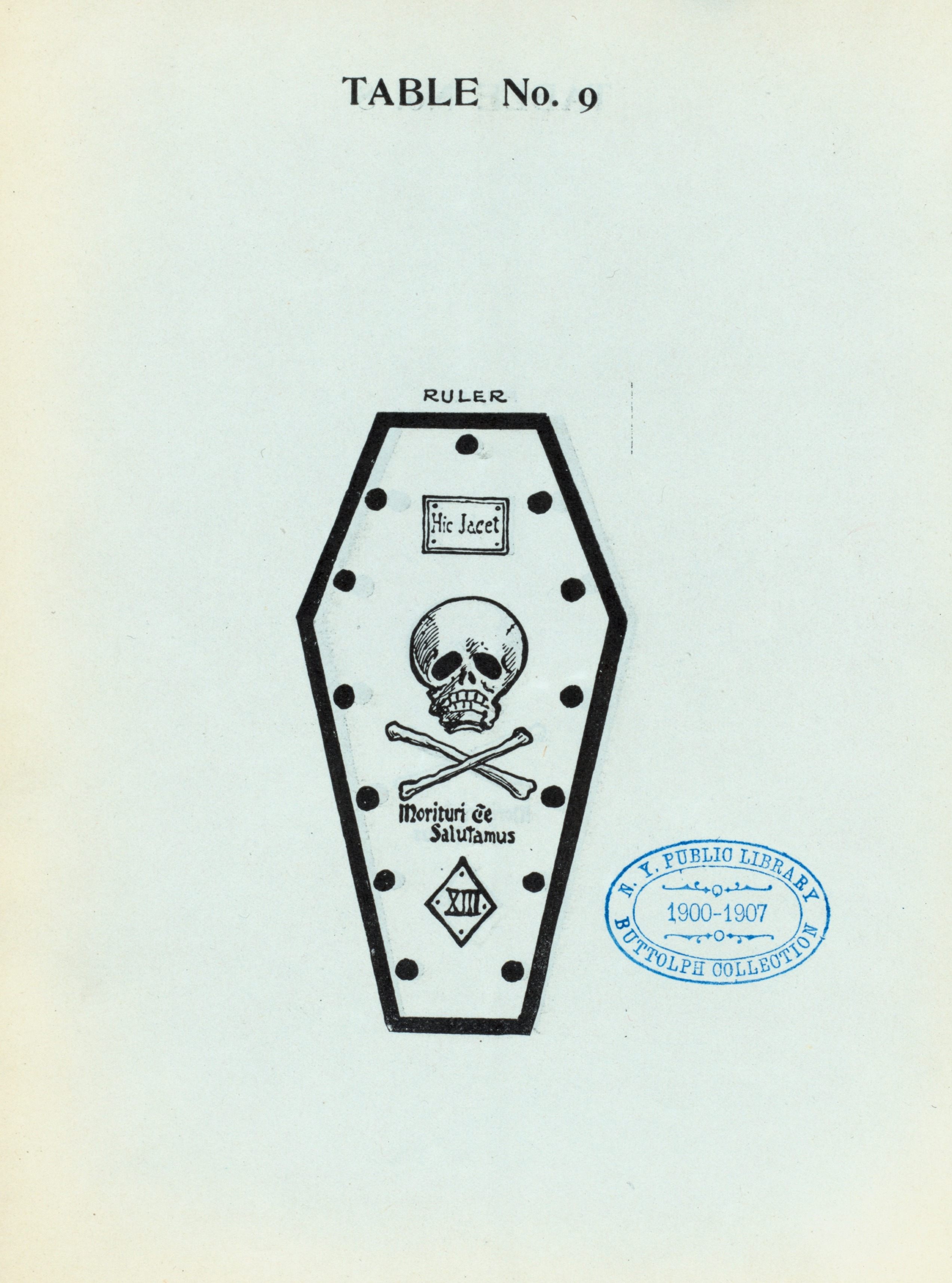

On September 13, 1881, in room 13 of Manhattan’s Knickerbocker Cottage, 12 expectant men sat around a table. The meal was all set out: big platters of lobster salad, each moulded into the shape of a coffin, surrounded by 13 crawfish. The decorations were perfect: 13 candles exactly, and a big banner that read ’Nos Mortituri te Salutamus‘—Latin for “We who are about to die salute you.” They were just waiting on one man.

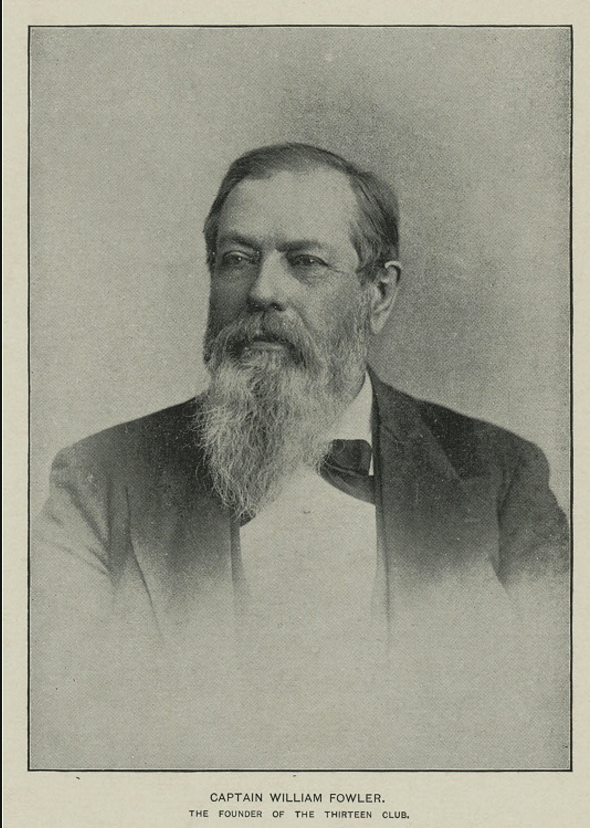

When an hour or so passed, and the last guest hadn’t shown himself, the dinner’s host, William Fowler, took matters into his own hands. Smiling, he grabbed a nearby waiter, who immediately began trembling. Fowler was just about to put the waiter through some initiation rites when the tardy invitee finally arrived. The frightened waiter was released, the first of 13 toasts was made—and thus began the inaugural meeting of the Thirteen Club.

In the murky annals of superstition, the number 13 maintains a special place. While historians aren’t quite sure why we don’t trust it, it can’t seem to shake its bad reputation. Fear of the number has been attributed, with varying degrees of evidence, to the Vikings, the Ancient Romans, and the people of 14th-century France. Even today, many new buildings still don’t have 13th floors.

In Fowler’s time, fear of the number 13 was most often associated with the Last Supper, where Jesus dined with his twelve disciples shortly before he was crucified. As one superstitious person explained in 1863, “since the Last Supper, whenever there are thirteen persons assembled, one of them is sure to be a Judas.” This belief was common enough to interrupt social occasions. Such luminaries as Victor Hugo would reportedly leave a table if exactly twelve other people were there.

Fowler himself, though, thought this was bunk. He’d lived a varied, happy life, and as he grew older, he realized that it featured repeated appearances by the number 13. He had attended P.S. 13, and graduated at age 13. During a brief stint as an architect, he built 13 public buildings. Later, he fought in the Union Army, and survived 13 battles. Eventually, he adopted the number as a sort of talisman.

Like many men of his time, Fowler had another great love: social clubs. (He eventually belonged to—you guessed it—13 of them, one of which was just him and one friend drinking boiling hot whiskey.) In the late 19th century, “club life” provided an easy way to make friends, eat lavish meals, and, in some cases, engage in various goofy, themed pursuits.

New York City boasted scores of these clubs—from the more traditional “Loto” and “Union” Clubs to the “Liar’s Club” (for men who loved to trick each other) and the “Candor Club” (for brutally honest ones). When Fowler took over the Knickerbocker Cottage, he decided it was time to found one himself. Its aim, he decided, would be to fight the fear of 13—and various other superstitions—by engaging in as many unlucky practices as possible.

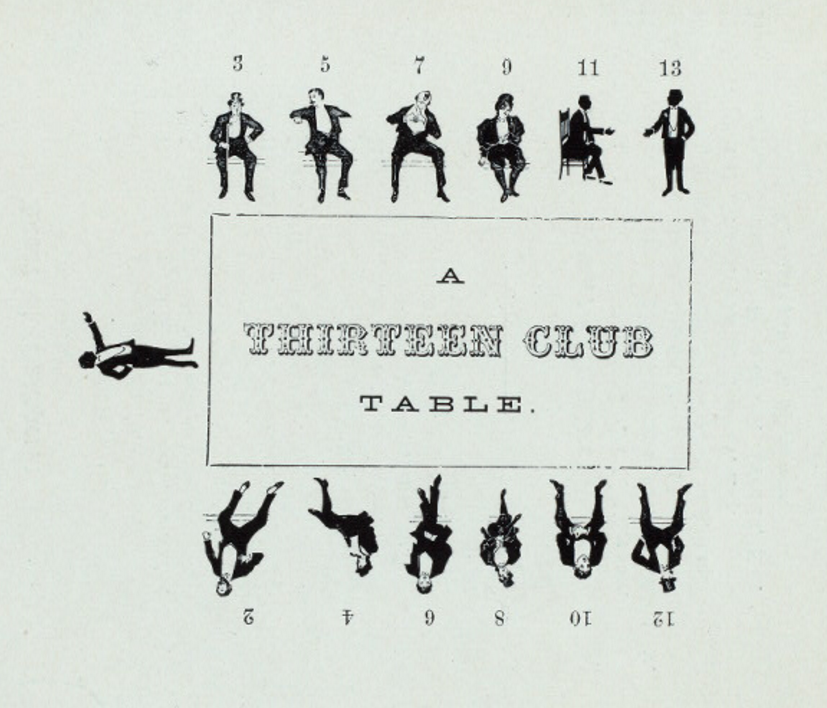

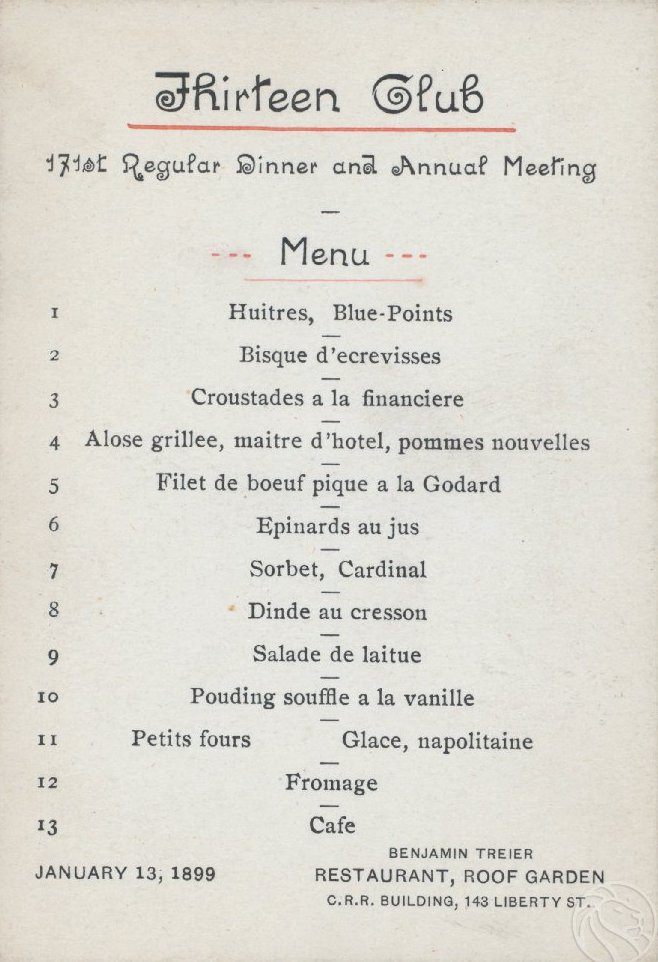

Although it took him nearly a year to drum up 12 other members, after their first meeting, the Thirteen Club began to grow, thanks largely to Fowler’s sense of humor and pitch-perfect flair for the gothic. Menus generally numbered 13 courses, and wine lists were often shaped like gravestones.

Members came dressed in black suits, neckties, and top hats; before sitting down, they made a point of walking under a ladder, brought indoors for the occasion. “The atmosphere was funereal, and suggested a feast at which undertakers only were bidden,” the New York Times wrote of April 1882’s meeting, which featured a cake with a black cat on it. Other meetings included mirror-smashing, salt-spilling, and mock trials of members who had purportedly acted superstitiously.

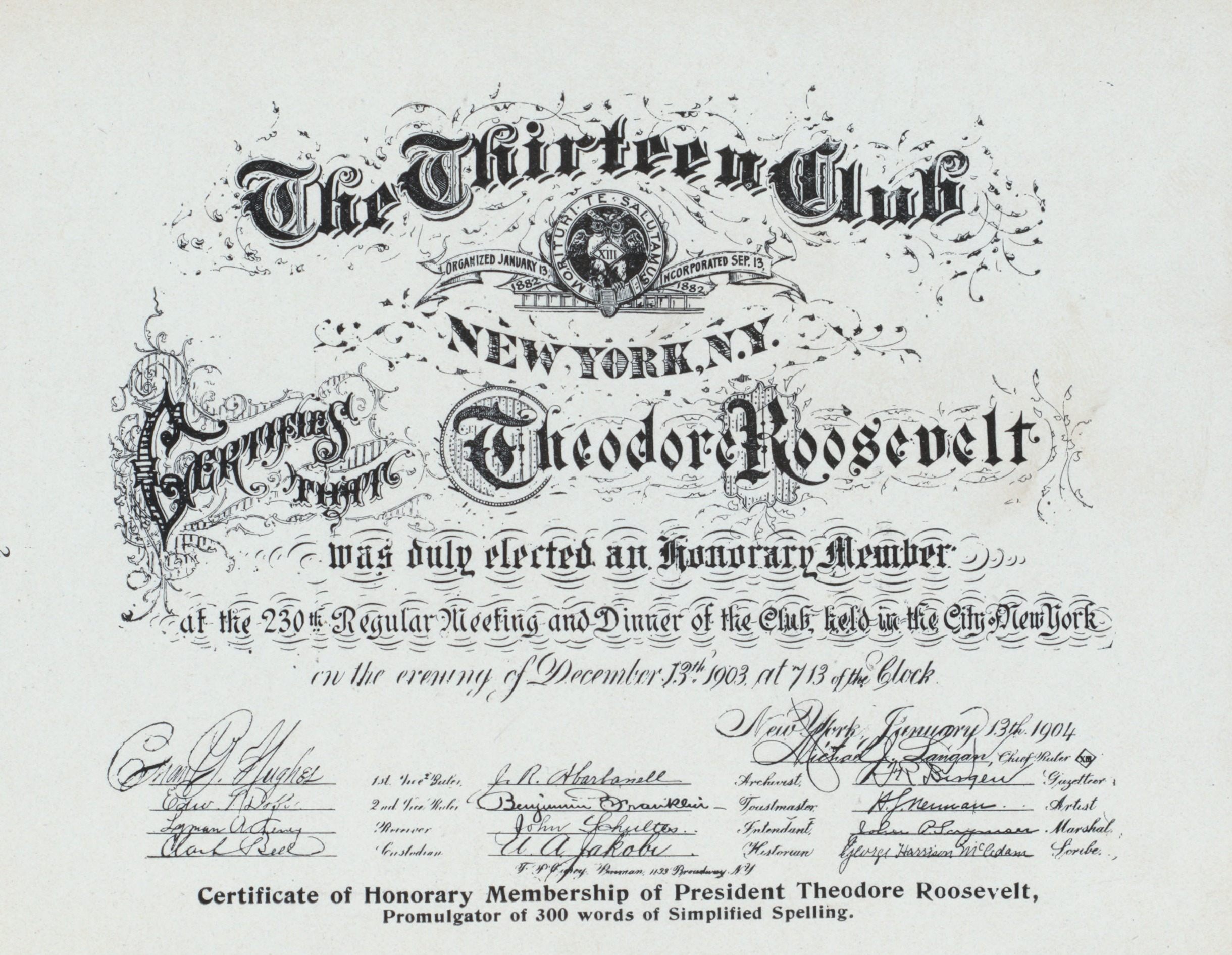

When they weren’t tempting fate at dinner, the Thirteen Club’s members advanced their cause in other ways. They wrote to local officials, asking them to rehabilitate Friday’s unlucky reputation by “inducing Judges to select some other day… for hangings.” (In at least one case, they succeeded.) They racked up high-profile honorary members, including Grover Cleveland, Chester A. Arthur, and Theodore Roosevelt. Some insisted on sitting only at tables of 13 even at other club meetings.

Word of these exploits spread quickly, and the Thirteen Club soon enjoyed a certain amount of renown. One 1886 dinner on Coney Island brought in 400 attendees. Chapters opened up in Chicago, France, and England. Sub-branches popped up, too, including New York City’s “Thirteen Cycle Club,” which traded lavish indoor banquets for outdoor clambakes. In 1891, New York’s flagship Thirteen Club began inviting women to certain dinners. (Each one got a welcome gift: a tiny glass bottle of perfume, with a stopper shaped like a human skull.) Two years later, 13 women opened up their very own chapter, in Iowa.

Despite this burgeoning popularity, though, some remained unimpressed. “The club has shown that it is as ignorant of the nature of ill-luck as it is reckless in trifling with it,” wrote one opponent in the Times. Bad luck did occasionally rear its head. At one club meeting, a waiter fractured his skull when the traditional indoor ladder collapsed on him. Another time, someone blew up the New Jersey clubhouse with dynamite. (The members inside escaped with bruises.) The club ran into some crying-wolf problems, too—after one New York meeting place collapsed in 1888, causing several injuries, officials were so busy joking about it that the club had to agitate for an investigation.

Mortality is the worst luck of all, and everyone dies eventually, even devoted flouters of superstition. Fowler passed away suddenly in 1897, and in the following decades, this particular type of club life began petering out. Starting around the mid-1920s, searching for the Thirteen Club in newspaper archives brings up only obituaries of former members.

But some unexpected bits of their legacy live on. According to one contemporary reporter, the Thirteen Club may be inadvertently responsible for one of today’s most iconic bad luck charms: Friday the 13th. Although both Friday and the number 13 have both been considered unlucky for centuries, it’s possible that no one made a point of combining them until the Thirteen Club, reporter Trevor Timpson writes. “Two of these vulgar superstitions you have combated resolutely and without flinching,” commended the club’s scribe in 1883. In their zeal to disprove each of them, the Club may have created a superstition superbug instead.

A short Times article, from 1887, also suggests the club may have had a hand in a piece of consistent good fortune: the weekend. That year, Justice David McAdam, a Thirteen Club branch president and a member of the New York City Court, declared Saturday an official half-holiday, during which public offices must close after noon. He did this, he said, partially to restore more esteem to Friday—a Thirteen Club priority.

“If the new idea met popular favor Friday might yet become the sailing day of all our ocean steamers,” the Times wrote, “And Saturday, now less than half a day for business purposes, would in a short time become a full holiday for pleasure.” About four decades later, in 1929, the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America successfully demanded a five-day work week.

So this Saturday, set aside a toast (or 13) for Fowler and the Thirteen Club—they might have the luckiest legacy of anyone.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook