A Hadza man gathers up his honey harvest, and burns the extra comb. (Photo: Brian Wood)

In the tree-strewn savannah of northern Tanzania, near the salty shores of Lake Eyasi, live some of the planet’s few remaining hunter-gatherers. Known as the Hadza, they live in Hadzaland, which stretches for about 4,000 square kilometers around the lake. No one is sure how long they’ve been there, but it could be since humans became human. As one anthropologist put it in a recent book, “their oral history contains no stories suggesting they came from some other place.”

Anthropologists have been scrutinizing the Hadza for centuries, seeking in their stories and behavior windows to the past. The Hadza themselves, at least at times, subscribe to a food-based method of self-understanding: they describe their predecessors based on what, and how, they ate. The first Hadza, the Akakaanebe, or “ancestors,” ate raw game, plentiful and easily slain–as one ethnographer relays, “they simply had to stare at an animal and it fell dead.” The second, the Tlaatlaanebe, ate fire-roasted meat, hunted with dogs. The third, the Hamakwabe, invented bows and arrows and cooking pots, and thus expanded the menu.

The Hamaishonebe, or “modern people”—the people of today—have a variety of meal strategies. Hadza hunting and gathering grounds are shrinking, under pressure from maize farms, herding grounds, and private game reserves, and some work jobs and buy food from their neighbors. But between two and three hundred of the 1300 Hadza remaining still survive almost entirely on wild foods: tubers, meat, fruit, and honey.

The greater honeyguide (Indicator indicator), friend to honey-lovers everywhere. (Photo: Wilferd Duckitt/Flickr)

Of these staples, honey is the Hadza’s overwhelming favorite. But beehives, located high up in thick-trunked baobabs and guarded fiercely by their stinging occupants, are hard to get at, and even harder to find. Enter the greater honeyguide, an unassuming black and white bird about the size of a robin. Greater honeyguides, a distinct species within the honeyguide family, love grubs and beeswax, and are great at locating hives. This is a boon for the Hadza, who, according to some estimates, get about 15 percent of their calories from honey.

When Hadza want to find honey, they shout and whistle a special tune. If a honeyguide is around, it’ll fly into the camp, chattering and fanning out its feathers. The Hadza, now on the hunt, chase it, grabbing their axes and torches and shouting “Wait!” They follow the honeyguide until it lands near its payload spot, pinpoint the correct tree, smoke out the bees, hack it open, and free the sweet combs from the nest. The honeyguide stays and watches.

It’s one of those stories that sounds like a fable—until you get to the end, where the lesson normally goes. Then it becomes a bit more confusing.

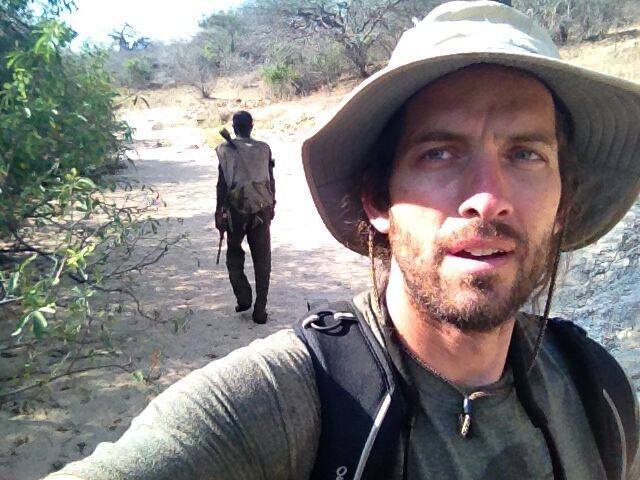

Brian Wood takes a selfie while following Pilot, a Hadza man, on a foraging run. (Photo: Brian Wood)

When Brian Wood, an assistant professor of biological anthropology at Yale, first heard about the honeyguide as a graduate student, he was surprised. Mutualism—when two different species interact in such a way that both of them benefit—is a main engine of the natural world: plants and pollinators need each other, as do gut microbes and mammals. But although people have played active roles in mutualisms in the past (domestication is likely the result of early agreements between, say, our and dogs’ wilder ancestors) such relationships between contemporary humans and untamed animals are practically unheard of. “This vague story of an amazing bird that flies in front of people and helps them find honey—it was almost too much to believe,” Wood says.

In 2004, though, Wood’s graduate work took him to Hadzaland. There, he followed the hunter-gatherers through the forest, studying what they ate and how they got it. “I had always imagined my work would be focusing on people sharing with other people,” Wood says—but, to his surprise, “a great deal” of Hadza foraging trips involved looping in a honeyguide. When Wood crunched the numbers later, he found that the birds were incredibly helpful. Not only did they lead foragers to more bee’s nests in a shorter amount of time, they found bigger, better nests for them, too. “My numbers indicate that anywhere from 8 to 10 percent of [the Hadza’s] whole diet is basically found with the help of this bird,” Wood says.

Two Hadza boys share a bumper honey harvest. (Photo: Brian Wood)

This wasn’t even the most startling part: the bird did this, Wood discovered, without the “mutual” part of the mutualism. Thanks to Hadza custom, the birds weren’t guaranteed any reward. Indeed, the Hadza were committed to stiffing their helper, meticulously destroying any grubs or wax that the honeyguide might make a meal from.

“I can go back into my notes to one of the very first times I was following a Hadza man,” Wood says. “I wrote down, ‘He’s taking the honeycomb and throwing it into the bush… he just grabs a handful of bee larvae and honeycomb and throws it into a tree.’” The second time, Wood says, the same thing happened: “He actually dug a hole and shoved the honeycomb that remained into it, and buried it.”

“I asked the Hadza guy to explain what was happening,” Wood says, “and his explanation was simply that they don’t want the honeyguide to get too full.” This would have impaired the bird’s work for the next day, according to the Hadza. Over and over, Wood watched foragers hide, bury, or burn excess wax, even when the birds were nowhere to be seen. In one video taken by Wood, a young man named Koyobe chews on some comb while detailing his reasoning. “If the honeyguide eats, she gets full,” he tells Wood, in Swahili. “Then she just would sit. She wouldn’t call.” Next to him, the remnants of a bee’s nest smolder in a fresh fire.

This fascinated Wood for a number of reasons. Ecologically, it meant the alliance wasn’t an equitable mutualism, but a less balanced type of relationship he calls manipulation. The term, familiar from human relationships, is basically the same in biology. In the words of the paper Wood published on his research, manipulation is “an act by partner A that causes partner B to alter its behavior in a way that is beneficial to A and marginally costly to B.”

Speculatively, it spurred thoughts of how such a relationship may have evolved. “I could imagine, for example, an early homo habilis or perhaps even an australopithecine already being an expert honey collector,” he says, the proto-honeyguide scrounging after the proto-human until the power balance shifted to bring the birds in as active partners, and then shifted again to cut them out. Anthropologically, it shed light on some more obscure aspects of Hadza mythology, where the honeyguide appears as a trickster in folktales and songs.

Spare honeycomb, tossed in the fire. (Photo: Brian Wood)

And empathetically, like many traditions, it clued Wood into the particular pressures of Hadza life. In a society where your human neighbor’s next meal depends on a bird staying hungry, refusing to feed it is, as Wood sums up, “the good thing to do.” It’s less about interspecies greed, and more about keeping the communal tools sharp.

Wood spent hundreds of hours tailing Hadza men, watching them forage and asking them why they did what they did. After seven years of annual trips to Tanzania, he and three coauthors gathered up their data and set out to make sense of it.

When they submitted their study for publication in late 2013, they fit as much as they could into it—detailed descriptions of the Hadza-honeyguide relationship, theories about how it arose, statistical proof of its efficiency. They ended their introduction on a cheerful note: “We hope this study will help foster an appreciation for the diverse ways in which people like the Hadza engage and influence their ecosystems, embedded in a full suite of species interactions.”

Search for honeyguides in the thickets of the internet, and you may be led to Wood’s research. But you might also run into a sweeter narrative. The Hadza aren’t the only people who team up with the greater honeyguide. Its range extends throughout sub-Saharan Africa, and other groups outside of Tanzania (in Kenya, the Congo Basin, and Mozambique, to name a few) have their own relationships with it. These relationships have fascinated visitors for centuries, particularly those with cameras.

These made-for-TV depictions are different than Wood’s, featuring sweeping aerial shots and voiceover narration. But most tell similar stories right up until the very end, where, on TV at least, the bird tends to get its due. On Discovery’s “Human Planet,” for example, two Maasai boys leave their feathery convoy a big chunk of comb. As the narrator says, they “know they have to pay their guide.”

If you’ve come across the BBC show “Trials of Life,” you might have even watched the exuberant David Attenborough share honey with the Kenyan bird who led him to a chock-full tree. “If the bird hadn’t shown us where this bee’s nest was, we would have never gotten this sweet reward,” he says, his mouth full of it. “But then, if we hadn’t broken open a bee’s nest, the bird would never have been able to get into the honey. Since it is a partnership, it’s only fair that the bird should get a reward. So it’s the custom in these parts not to take all the honey, but to give some of it to the bird.” He molds a piece of waxy comb around the tip of a spear stuck in the ground, and is on his way.

A still from the honeyguide scene in “The Hadza: Last of the First” in which a honeyguide enjoys leftover comb. Wood says the scene is “obviously staged.” (Screencap: Hadza Movie/YouTube)

Many people and groups of people do make a point of rewarding honeyguides, and Wood knows that these filmed depictions might reflect reality. “I think that there’s likely to be a whole set of different ways that humans and honeyguides relate to one another, in different places and times and different contexts,” he says.

More troubling to him is a recent documentary, called Hadza: Last of the First, shot at the field site where he does his research. In one scene of the film, after a group of Hadza men smokes bees out of a hive, they are shown throwing pieces of the honeycomb, which hit the ground in slow motion. The bird, filmed in close-up on a flattened patch of grass, snaps them up. A narrator explains, “The bird will wait patiently and fly down, and will essentially take the leftovers… it’s the most developed, co-evolved, mutually helpful relationship between any mammal and any bird.”

As Wood soon found out, this story of sharing is not just sweeter, but stickier. Soon after he submitted his article to the journal Evolution & Human Behavior, he received pushback from a reviewer who had come across Hadza: Last of the First. “The reviewer said ‘I know this [paper] can’t be right, because I’ve seen on YouTube that the Hadza repay honeyguides,’” says Wood. (The scene, Wood says, is “obviously staged.”) “I had to bear down, dig in the trenches, and write the world’s longest letter to the editor,” he says. To describe what he saw in the film, Wood invoked a term coined a century ago: “This is naturefaking.”

A Hadza man brings home some comb. (Photo: Brian Wood)

In 1907, then-President Theodore Roosevelt took a break from the year’s various Immigration Acts and Gentlemen’s Agreements to hold a very different group of people to task: the “Nature Fakers,” who, he said, were filling the country’s books and periodicals with starry-eyed tales of the outdoors. These “yellow journalists of the woods” anthropomorphized animals recklessly, mistook fables for facts, and trusted “irresponsible guides,” wrote Roosevelt in the popular general interest periodical Everybody’s Magazine. “Much remains to be told about the wolf and the bear, the lynx and the fisher, the moose and the caribou,” he continued. “But he is not a student of nature at all… whose imagination is used not to interpret facts, but to invent them.”

According to historian James Perrin Warren, this was “the first and only time in American history the president acted as a literary and cultural critic.” It worked. The Reprimander-in-Chief’s words marked the beginning of the end of what would eventually become known as the “nature fakers controversy,” during which more sentimental wilderness writers clashed with more scientific ones.

But it was just the beginning of naturefaking as a general practice. With the advent of documentary filmmaking, those seeking to capture particularly outlandish animal behavior could just stage it instead. For Disney’s 1958 “documentary” White Wilderness, a camera crew hoping to film the “suicidal mass migrations” of Arctic lemmings ended up trapping a bunch of wild ones and chasing them off a cliff. As Derek Bousé relates in his book Wildlife Films, this begun the age of “animal cops and robbers shows,” where wild life was tweaked to imitate art: birds scared off branches at dramatically opportune times, carnivores forced into confrontations, megafauna shoehorned into suspiciously human storylines. This tendency has translated well to new media, too. A few years ago, a different centuries-old honeyguide misconception, this one suggesting that they also lead honey badgers to hives, returned in the form of a cleverly edited YouTube video.

Though throwing a bunch of lemmings into the sea is objectively terrible, naturefaking seems pretty low on the world’s hierarchy of bad deeds. But pull off the same type of fake enough times, some experts say, and the consequences can become more virulent. In his influential work “The Trouble With Wilderness,” environmentalist William Cronon argues that the predominant Western idea of nature as a sacred and untouched space is itself an enormous myth, forged from an alliance between European romanticism and the American drive toward the frontier. “We too easily imagine that what we behold is Nature when in fact we see the reflection of our own unexamined longings and desires,” he writes. Such mythologizing blinds us, both to actual nature and to those desires, and prevents us from engaging properly with either. It encourages environmentalists to seek an impossible future, he says, in the form of a return to a nonexistent past.

According to Susanna Lidström, who researches nature narratives at the University of California, San Diego, this overarching concept has influenced how we think about everything from poetry to politics. “This persistent idea, about indigenous people living in some sort of harmony with nature, reappears in many different contexts,” says Lidström. “It’s a very sweeping narrative that doesn’t allow for much detail or nuance.” Besides, when examined more closely, the concepts within the idea break down, too. “You can’t really describe an ecosystem as being in harmony,” she says. “[The word] is not really relevant in that context.”

Even if this idea of balance and harmony has little bearing on reality, it has influenced how we order the natural world in our heads, Lidström says. For instance, she continues, the idea that invasive species are intrinsically harmful has been so successful, it has overgrown the science that originally inspired it. The narrative abstracts complex relationships into less subtle talking points, with “very linear definitions of perpetrators and villains.” Though a number of introduced species do wreak havoc on their environments, those that don’t get swallowed up in this story, which also makes such categorizations look “as if they happen outside of human decision-making and values.” Suddenly, California eucalyptus becomes an enemy of the state, and George W. Bush begins spending his vacation time waging war on tamarisk trees. Or a particularly nasty-looking weed like kudzu—which, as naturalist Bill Finch detailed in Smithsonian last fall, is more metaphorically than botanically meddlesome—becomes The Vine That Ate The South.

It’s the magnetic pull of such narratives, Wood fears, that feeds into smaller-scale mythologizing–like that of the honeyguides and the Hadza, who, as hunter-gatherers, are frequent targets of romantic generalizations. “People try to use it as a kind of ‘just-so’ moral tale: that this can give you a glimpse of the moral dimension of hunting and gathering, and could unlock some kind of deeper truth about human nature,” he says. “There’s been a lot of resistance to recognizing that there’s a utilitarian explanation for this.”

Or, as Wood puts it, if you expect hunter-gatherers to achieve, or even to want, a particular sort of harmony, “you’re going to be sorely disappointed.”

Gemu, a Hadza forager, smokes the bees out of a baobab tree. (Photo: Brian Wood)

Wood got his paper published. But since encountering that initial pushback, he has developed a keen eye for this particular brand of naturefaking. He keeps a file of all the depictions of honeyguides he has ever come across, going back to 1777, when a Swedish naturalist named Anders Sparrman sent a dispatch from the Cape of Good Hope describing a “curious species of Cuckow” known for “discovering wild-honey to travellers.” (“The bee-hunters never fail to leave a small portion for their conductor, but commonly take care not to leave so much as would satisfy its hunger,” Sparrman continues, equivocally. “The bird’s appetite being only whetted by this parsimony, it is obliged to commit a second treason, by discovering another bee’s-nest, in hopes of a better salary.”)

Rampant anthropomorphizing aside, “whoever [Sparrman] was talking to gave him the straight dope,” Wood says. (Sparrman also gave the greater honeyguide its fitting scientific name: Indicator indicator.) But things went downhill after that. “Throughout the 20th century there is this growing mythologization of this relationship,” he says–Laurens van der Post citing the “magic and religious revelation” of the Bushmen-honeyguide alliance, for instance, or William Swainson’s specimen “patiently waiting for that portion that is always left by the African hunters as a reward.” And after that, of course, come the excitable, authoritative narrators of YouTube.

From all of this, Wood has gleaned a sort of perpendicular message from the Hadza. “I propose that the moral conundrum that the Hadza might be facing is totally different than what we in the West might be imagining,” he says, one centered not on being fair to honeyguides, but on making sure fellow foragers get fed.

An illustration of the honeyguide from 1838. (Image: Nicholas Huet le Jeune & Jean-Gabriel Prêtre/WikiCommons Public Domain)

Other sources take different lessons from the honeyguide chronicles. Clapperton Mavhunga, an associate professor of Science, Technology and Society at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, comes to the situation with a distinct frame of reference. Growing up in Zimbabwe, Mavhunga spent much of his childhood raiding bee’s nest after bee’s nest with the help of the honeyguide. “In my own culture, the saying is that it can either lead to you honey, or it can lead you to an Egyptian cobra,” he says.

Though he trusts Wood’s observations, Edmond Dounias, an ethnobiologist who studies honeyguides in the Congo, says that this sharing framework is, in his experience, more common. “To my knowledge, the Hadza are the only honeyguide partners who try to cheat the partnership,” he writes in an email. “In the societies I’ve worked with, rewarding the bird is a recognition of its crucial role and an expression of respect.”

Such a stark cultural difference raises important questions, Mavhunga says. The Hadza are coming under increased pressure from governments and NGOs that seek fast development. It’s worth considering that they may have adapted their honeyguide strategy more recently as a result of these changes, he says. (Wood says that, after speaking to a number of Hadza and a number of fellow researchers, he has seen no evidence that the Hadza have ever repaid honeyguides.)

Hadza people hanging out under a tree. (Photo: Brian Wood)

Even if they did not, it’s vital to understand the Hadza’s decisions within the contexts in which they arose, especially when such decisions can be twisted to encourage particular outcomes, says Mavhunga. This is another, even more insidious part of naturefaking’s legacy: groups whose practices don’t jibe with harmonious narratives can be left out of conservation decisions, or even forced off of their land.

Centuries of colonialism have given us particular grids–the scientific method included–on which indigenous ideas and experiences are not always easily plotted. “For one to have a relationship with a bird like a honeyguide, one has to have thoroughly studied and understood its ways,” Mavhunga says.

Even that is just a small portion of a larger understanding, one that must take into account Hadza faith, ethics, philosophy, and current events. “Be very careful, because what you are looking for here are not your reasons,” he says. “It’s the Hadza’s reasons.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook