The Ballad of Lucille Mulhall, America’s Original Cowgirl

As a 14-year old, she roped steers in front of President Roosevelt.

At a Rough Riders reunion in Oklahoma City in 1900, Theodore Roosevelt watched as the 14-year-old girl galloped her horse, swinging a lasso overhead. When she roped around a running steer, she beat sun-weathered cowboys for first prize. Afterward, Roosevelt bowed to the girl and told her that none of his troops could have done a better job.

The girl’s father, Zach Mulhall, later said that Roosevelt urged him to take her on the road. The country needed to see Lucille.

Lucille Mulhall was known as the first—or original—cowgirl. She introduced countless audiences to the idea that a woman could rope and ride better than men. “Although she weighs only 90 pounds she can break a broncho, lasso and brand a steer and shoot a coyote at 500 yards,” wrote one reporter. Mulhall became a symbol of the Old West as it ebbed away with the turn of the century. With her ranching background and daring rodeo performances, Mulhall linked herself to open spaces and the freedom found riding astride in a divided skirt and Western saddle.

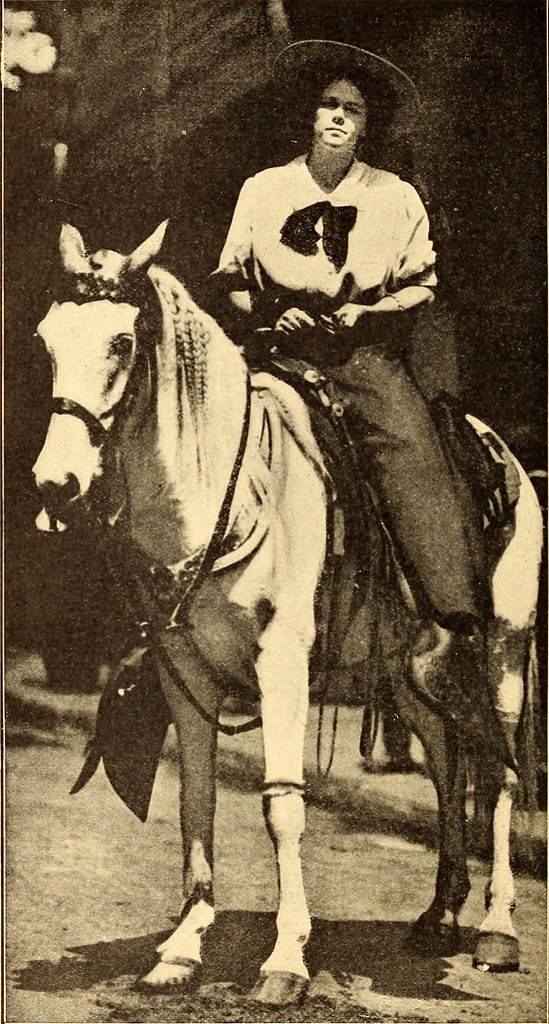

Mulhall at the 1912 Calgary Stampede. (Photo: Courtey Calgary Stampede)

In one routine, Mulhall roped eight galloping horses; in another, she lassoed a “horse thief,” and then cowboys pretended to hang him. Lucille’s trick horse, Governor, could kneel, play dead, ring a bell, take off Lucille’s hat, and sit back while crossing his forelegs, like a bored spectator. Mulhall’s company performed in New York City, and with their time off they thundered through Central Park in full Western regalia. A young Will Rogers, Mulhall’s early co-star who went on to enormous fame as a performer and humorist, performed rope tricks alongside her, and Tom Mix, who would become a leading movie cowboy, rode with the Mulhalls, too.

Sometimes, things got truly wild: at one event, a steer got loose and bolted up some steps, scattering spectators. The steer then tossed an usher who tried to grab his horns, and vanished behind the box seats. Will Rogers headed the steer off and rushed him back down the steps, hooves clattering, to the ring. During all this, people heard Zach Mulhall shouting at his daughter. Why did Lucille not “follow that baby up the stairs and bring him back”?

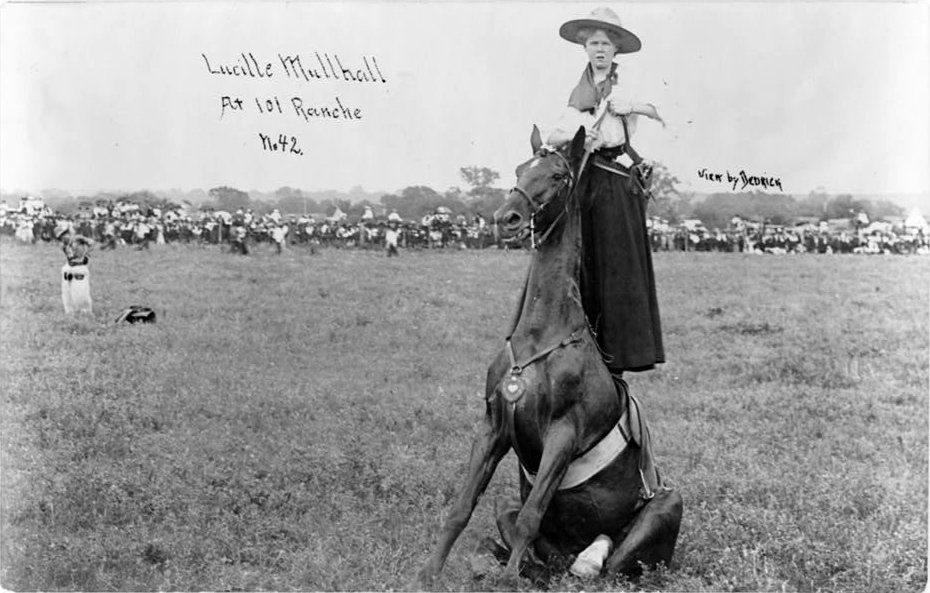

Mulhall standing on the back of a seated horse, 1909. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-126135)

Mulhall provided some rich fodder for the florid prose of the day. Here’s a reporter describing her background in 1903: “The plucky maid of the mountains was born and brought up, a veritable child of nature, on a ranch in Oklahoma. Instead of a baby’s rattle she heard the tinkle of spurs. Her cradle was the saddle. She cannot recall a time when she could not ride a horse.” Mulhall gave lively quotes, too. “I feel sorry for the girls who never lived on a cattle ranch and have to attend so many teas, and be indoors so much, with never anything but artificiality about them,” she told a St. Louis reporter in 1902.

Mulhall in 1908. (Photo: Public Domain)

President Roosevelt wanted an Oklahoma wolf, Mulhall said in 1905. But he would only accept it on the condition that she roped it herself. She promised, and sighted the wolf she wanted: a gray one, as big as a year-old steer. Mulhall chased the wolf through canyons and over prairies, and roped him once only to have him chew through her lariat and escape. Finally, he wore himself out. She captured him, and sent his pelt to a taxidermist in Saint Louis. Next, it was shipped, express, to Oyster Bay, for Roosevelt’s curio room. “I have a letter from Mrs. Roosevelt telling about the arrival of Mr. Wolf,” noted Mulhall. “She said that it was amusing to see the way the dogs acted when they saw him come in the house.” Later, Roosevelt gave Mulhall a saddle.

By 1916, Mulhall was producing her own rodeo. Lucille Mulhall’s Big Round-Up showcased bucking horses and roping contests. With the Round-Up, Mulhall could also offer competition and employment for other cowgirls, no longer a novelty.

Mulhall with her horse. (Photo: liz west/CC BY 2.0)

But for Will Rogers, Mulhall would always be the first cowgirl, he wrote in 1931: “There was no such thing or no such word up to then.” That same year, Mulhall also noted a changing of the guard. “Something has passed with the old life,” she said. “This new day is probably fine, too, but I loved the unfenced range and the open prairie and the boundless friendliness of the cattle country.”

Mulhall’s last public appearance was in September of 1940; she died in a car accident that December. On the day of her funeral, the Oklahoma mud was so slippery that cars were useless, so a neighbor’s plow horse pulled her hearse. “A machine killed Lucille Mulhall,” reported the Daily Oklahoman, “but horses brought her to her final resting place.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook