How the Skort Went From Rebellious Garment to Athleisure Staple

The skort has always been a divisive piece of clothing—literally.

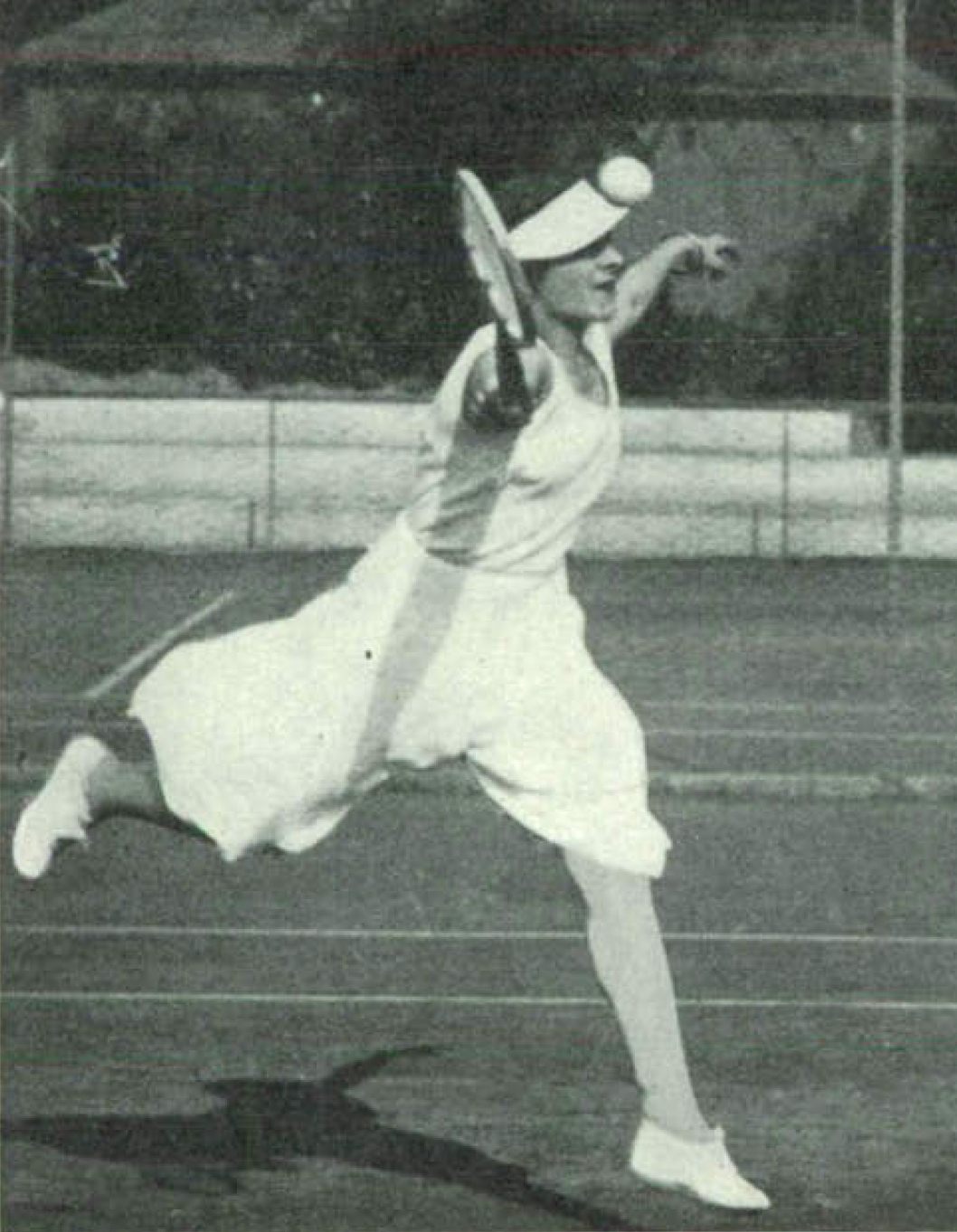

Today, the skort—a portmanteau of skirt and shorts—is most often associated with female tennis players dodging across a tennis court, Spandex-like bike shorts beneath an A-line mini fluttering in the wind serving two purposes: modesty so a woman can spread her legs without flashing the world while retaining a sense of traditional femininity.

But the history of the skort doesn’t begin with tennis. Instead, the skort’s real path to mainstream acceptance can be traced to a fad that hit America hard in the late 1890s: bicycling.

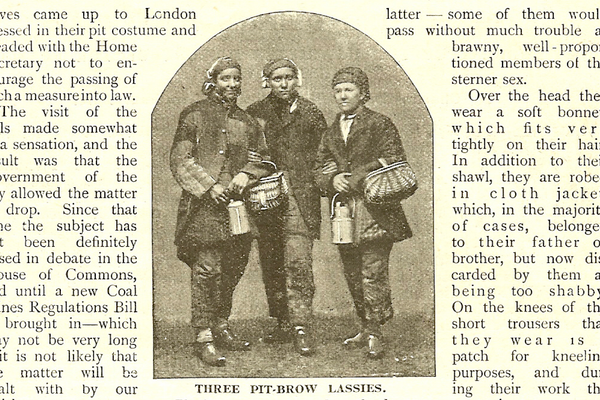

The first skorts were actually referred to as “trouser skirts,” a clunky but apt name describing the outfit’s dual identity. While non-Western cultures had long experimented with drapey pants for women—the salwar of South Asia, the gathered-at-the-ankle jodhpurish pants of the Amazons—pants were, and in many more conservative cultures continue to be, considered virulently masculine and obscene for women to co-opt.

But in the 1890s, bicycling rose from mere spectacle to sport, and a trendy one at that. The design had immensely improved from its previous “boneshaker” design, allowing the rider to balance more comfortably on two similar-sized, air-filled wheels and a metal chain that kept said wheels moving. On these new and improved bicycles, a woman could independently move about—a fact that both perplexed and horrified males and women alike, who couldn’t fathom why early feminists like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton were so enamored of speeding around on two wheels.

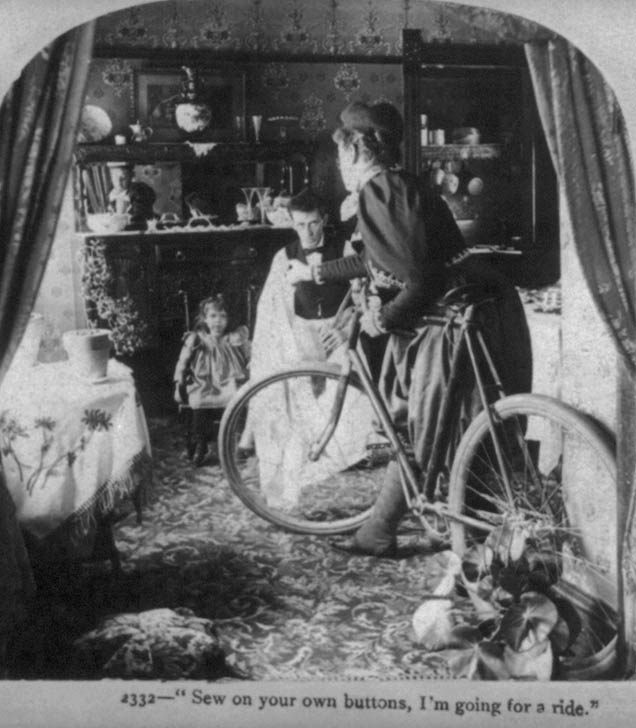

And as anyone who’s ridden a bike knows, having an article of clothing between your ankle and the metal chain that keeps the wheels whirring is asking for a tumble. That meant the florid fashion of the Victorian age was especially ill-equipped for a ride around town. As a 2014 piece in the Atlantic notes, this introduced the first radicalized statement in women’s fashion, with exposed ankles and bloomers making the socially proper gasp in shock at what they viewed as outright impropriety and impunity at social norms.

Today, the act of donning pants beneath a skirt might seem almost conservative, but Keren Ben-Horin, a fashion historian and author of She’s Got Legs: A History of Hemlines and Fashion, says that the “trouser-pants” that biking demanded of women made for a stunning statement of independence. “It was very forward,” Ben-Horin says. “And it was only worn as athletic attire, not as street clothes.”

Indeed, the first skorts doubled as the first athleisure, though it was nothing like the sleek, moisture-wicking, body-defining outfits we associate with Lululemon yoga pants. The first skorts were wide-legged pants beneath a panel that buttoned up double-breast style to hide the fact that there was a pair of pants below the skirt. “They weren’t bifurcated garments, and the pants part weren’t really shorts,” says Deirdre Clemente, a professor of history at the University of Las Vegas specializing in the fashion industry. “They were more like a skirt with a flat front, and they were very baggy.”

But these garments were revolutionary in that fashion at the time emphasized a voluminous behind (usually created with a corset and cage) and a flat front. “Big bosom, big sleeves, big behind,” Ben-Horin says. The trouser pants reversed that concept. “It brought up a lot of questions,” Ben-Horin points out, “about what it means to be a woman, what it means to behave properly, what it means to be a woman wearing pants. This was infringing on men’s power and a man’s role in society by wearing something considered masculine; if you are wearing pants, you are infringing on this power men assert.”

As with many a fashion trend, the French were the first to make skorts cool. It was World War I and women were redefining fashion and utility, questioning the Victorian era’s emphasis on ruffles and impractical layering amid the newfangled idea that clothing should prioritize ease of movement. What’s more was the era’s fascination with Orientalism: Westerners were fascinated by the spoils of colonialism and what they saw as “exotic”—namely, harem pants, dense and intricate embroidery, and more fluid lines that allowed a woman to walk and not teeter-totter precariously in a literal cage. Parisian couture houses began showcasing heavily embroidered trouser skirts that could be worn at home or as costumes, deemed more as whimsical vestiges of far-off lands than a practical thing to sling on for errand-running.

In an ironic twist, dancing brought the masculine-straddling skort to the mainstream. Ben-Horin traces the trouser skirt’s blowup in popularity to Irene Castle, who—along with her husband Vernon—is credited with making ballroom dancing fashionable in the wake of World War I. The Castles dancing expertise was immensely popular on silent film and involved quick twirls that required complex footwork. Those Victorian era frou-frou gowns were an impediment and basically useless. Castle is credited for not only ushering in the flapper era with her bob and slinky, shin-skimming dresses, but also having a thing for “split skirts,” or a skirt that was divided like harem pants, with front-covering pleats that made it look outwardly like any other dress. That freedom of movement combined with flapper-era trendiness was enough to get upper-crust females to don pants under their skirts.

Clemente says the skort’s rise also shadowed the rise of synthetic fabrics like rayon, which had just been invented. “It made mass production possible for women,” she says. Previously, women’s fashion was very much tailor-driven, but the skort was an off-the-rack purchase for going dancing, and could be produced cheaply thanks to manmade fibers. Rayon also took to dyes better, introducing color that took away from the drab, dull, beige-ish hues that dominated the Victorian era and allowed women to express themselves in more vibrant tones.

That produced a trickle-down effect from women to girls: Clemente says that rayon’s unique capability to be used in skorts meant that college-age women began adopting a variation of the skort as uniforms for gym class, which appeased administrators in having the appearance of the skirt while allowing female athletes to run and jump without the restrictions of a skirt. “It was the first time you really saw the spending power of young women,” Clemente says. “These women under 30 were navigating social norms and dictating purchases. And with rayon, they were able to buy two of something their mother would only buy one of.”

“The skort got sidelined after 1930,” says Clemente, mentioning that society had come around to seeing women wearing shortened pants, making the front panel and pretension of a skirt unnecessary. “They were still very popular among tennis players, but they lost their prominence.” But Alvarez singlehandedly made it permissible for women to wear pants to work—if a woman could flounce around a court in loose culottes parading as a skirt, then society was fine with a woman wearing pants. And Alvarez’s version of the skort helped democratize the article of clothing—previously, its audience was solely white, well-off, and able to afford the leisure time sports afforded them. Now, the skort was a practical item, something that a woman could wear jogging, or a girl could don for soccer practice.

Yet the skort was relegated to the world of sports and not of popular fashion, and Clemente has a theory why. “Skorts represent the compromise between the offensive—shorts—and the polite, the skirt,” she says. “Skorts had an element of formality of the traditional garment, but you were getting these modern elements of movement and freedom, too. Shorts were associated with masculinity, but when they became acceptable, it wasn’t necessary for women to wear a skort any more.”

It took another world war and a couple more decades of hemline hiking for the skort as we know it—an above-the-knee contraption that’s got an A-line cut and bike shorts below it—to really take hold. By the 1960s, thanks to miniskirts and the counterculture revolution, the skort bobbed to the surface. “It was very fashion forward, for free-spirited women,” Ben-Horin says. “It never really became a fad so much as a statement for freedom of movement.”

“One thing with the skort was that it pleased both men and women,” Clemente says. “Femininity is something that men forced upon us. Men defined what is feminine and what is not feminine. The skort let women retain their femininity but also let women define femininity for themselves.”

That’s the thing about the skort: Its quiet rebelliousness might have some thinking that it’s in disguise as a skirt, offering traditional modesty for its wearer. The skort’s ability to rise above the boxes of masculinity and femininity, to be pants and skirt in one, mean it’s importantly able to be more than a cute portmanteau. Without the skort, it would have been nearly impossible to kickstart the women’s sports revolution in America. Without the skort, gender roles in fashion—a man should wear pants and a woman should wear a skirt—would have been difficult to transcend. Without the skort, some of today’s biggest trends for the lower half of the body—swooshy big pants, calf-grazing skirts, religiously observant and modest fashion, and of course, athleisure—would have been nearly impossible to conceive of and even more difficult to sell to a broad audience.

“Skorts are crazily important,” Clemente says of the garment’s role in feminism. Don’t let its indecision about being neither shorts nor a skirt fool you: The skort is revolutionary.

*Update: The article originally stated that at Wimbledon in 1931, Lili Alvarez wasn’t wearing stockings. She was wearing stockings, but her opponent wasn’t.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook