The Iraqi Version of ‘What’s Up?’ Is an Existential Riddle

The phrase “shaku maku” offers a question, a playful paradox, and an invitation to share.

In the Middle East, a region of made-up borders and increasingly meaningless flags, language is identity. If an Arab man walks into a bar and says Zayek!, he’s Egyptian. If his Arabic is light and sing-songy, almost French, he’s from the Levant. If he says Shaku maku!, he is definitely Iraqi.

But in Iraq, a country that delights in fooling the uninitiated, shaku maku isn’t just a greeting. It’s a paradox. Roughly translated, it means: “What is everything and nothing?” Said anywhere else, it would sound like a joke.

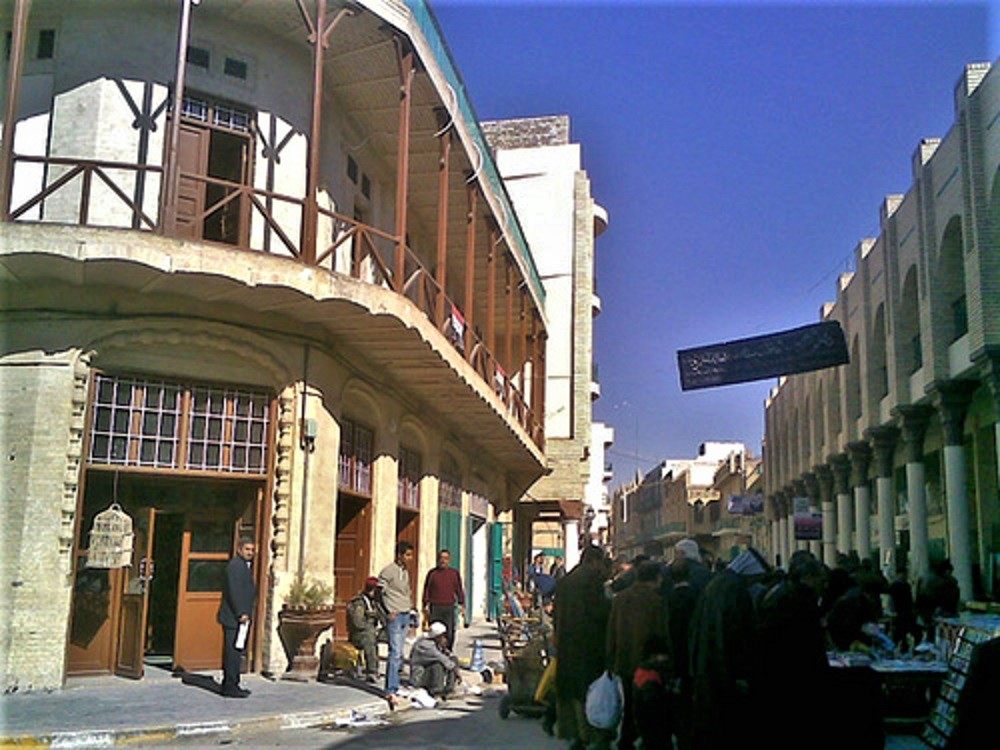

The riddle at the heart of shaku maku seems to sum up the contradictions of the modern Iraqi experience. Baghdad, once a capital of literature, learning and high society, is now a grim city of endless checkpoints. The institution of Arab hospitality, elemental to Iraqi society, has been deeply damaged by years of sectarian warfare. A country where literacy was once near-universal now struggles to educate its children.

When you’ve lived with this for longer than you can remember, perhaps it makes sense to greet someone with an existential shrug.

Iraqi is perhaps the heaviest and the harshest-sounding of the Arabic dialects. “People often sound like they’re arguing,” says Zena Agha, a London-raised Iraqi-Palestinian. What it lacks in music, she says, it makes up for in its sly wit: “Levantine Arabic is more delicate, softer, melodic. But it’s not as funny in the way Iraqi Arabic is.”

Little has been written on the origins of shaku maku (شكو ماكو in Arabic), and what little exists can’t seem to agree; Hussein Kadhim, an associate professor of Arabic at Dartmouth University, said its origins “remain obscure” and that while there’s plenty of speculation, “none of [it] is reliable, and I would not feel comfortable recommending any of it.”

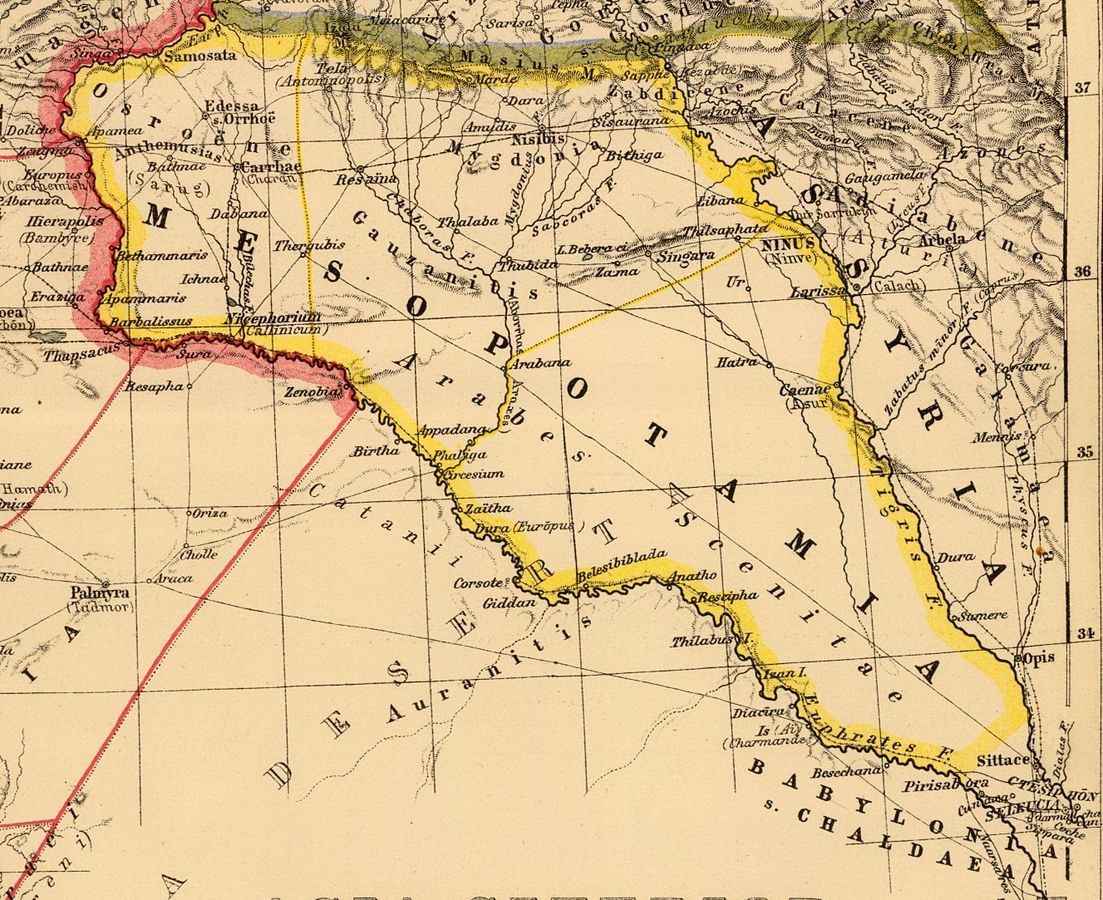

While accounts lack consensus, all point to ancient origins. Akeel Abbas al-Khakani, assistant professor at the American University of Iraq Sulimaniyah, credits Akkadian, the language of ancient Mesopotamia: akoon means “there is, or exists” he wrote in an email. Assimilated into Arabic, it becomes aku; add sha, which means “what,” and the negating ma, and you have shaku maku: what exists, what does not exist? “So it is an entire survey of somebody’s life in one sentence,” al-Khakani said.

Crucially, the phrase respects the strict division between public and private life that runs through Middle Eastern cultures: when asked shaku maku, one can offer everything or nothing in response. The phrase tests a willingness to engage in a long conversation, al-Khakani writes, and the response, warm or restrained, sets the ground rules.

Maku shi (“There’s nothing”) or alhamdulilah (“Praise be to god,” functionally meaning “All good”) are the easy ways out. They get the conversation going. But if you ask—particularly if you ask someone who trusts you—you might get the full litany of joys and sorrows.

“In other words,” writes al-Khakani, “it condenses the interplay of opposing forces: desire and discipline, individuality and sociality, and interest and disinterest, all cast in a measured, respectful, but nonetheless ambitious, phrase.”

Which is a lot to fit in “what’s up?”

For Agha, who is studying the Palestinian Territories for her master’s thesis at Harvard University, the phrase immediately flags her as Iraqi. Arabic speakers of the Levant (Syrians, Lebanese, Palestinians) have a similar phrase, she says—shufi shumafi—but it’s rarely used, and it doesn’t carry the same sense of humor.

“It’s kind of got a twinkle in the eye—tell me, I want to know,” even if you don’t really want to know, she says. “Even as it asks something profound of you, it’s very cheeky.” Another Iraqi signature, shlonik, is similarly playful: instead of simply asking how you are, it asks: “What is your color?”

During the two years I spent in Baghdad working for the U.S. Agency for International Development, I heard shaku maku every day. I answered casually with maku shi, as did many of my Iraqi colleagues. The question wasn’t always freighted with a sense of paradox, nor was their response. But it didn’t have to be: they spent hours in grueling checkpoint traffic just to get inside the Embassy walls, and now they were looking out at their city from the green tint of blast-proof windows. That’s paradox enough.

“I think it might show the confused and curious Iraqi personality,” says Iraqi expatriate and Chevy Chase, Maryland resident Ali Sada, of shaku maku. “It shows that we care about everything that happened with the other, but also it shows we don’t know anything specific, so we come up with this weird question.”

Sada grew up in Nasiriyah, in Iraq’s predominantly Shi’a south. He was imprisoned by Saddam Hussein, exiled to Jordan, and returned to Baghdad to help the “coalition of the willing” build democracy in Mesopotamia, spending years working on western-backed civil society projects.

“For me, I was born with shaku maku in my blood,” he says. “I see it perfectly normal. Nothing unusual about it.”

Maybe shaku maku is just a phrase. Or maybe it really does gather the Iraqi experience—the smirking humor, the fatalism—into two words. Maybe it’s everything. Maybe it’s nothing.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook