Found: Hidden Examples of Long-Lost Languages in Centuries-Old Palimpsests

New imaging techniques are revealing texts that were erased hundreds of years ago.

Saint Catherine’s Monastery has been standing at the foot of Mount Sinai, of Biblical fame, for 1,500 years. One of its attractions is its extensive library, which holds thousands of early books and thousands more manuscripts.

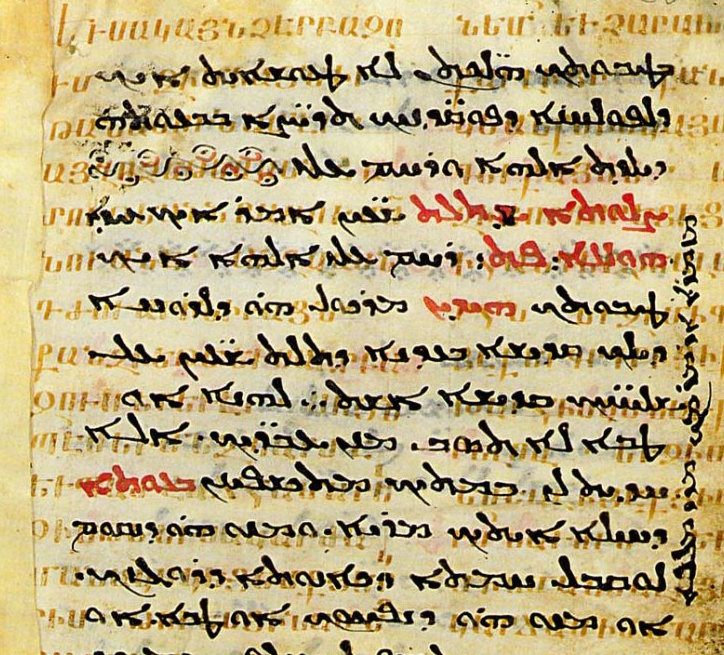

Among those handwritten manuscripts are 130 that have additional secrets: They are palimpsests, documents in which the original text was erased and written over, the parchment considered more valuable than the text. Over the past few years, though, researchers have been able to reveal the “undertext” of those manuscripts—the long-lost words that were wiped away hundreds of years ago, The Times reports.

Their discoveries included two rare texts of Caucasian Albanian, an obscure language known mostly from snippets of stone inscriptions, and examples of Christian Palestinian Aramaic, a hybrid Syraic-Greek language that’s been dead for 800 years.

The original writing on the palimpsests was erased anywhere between the 4th and 12th century, according to the Early Manuscripts Electronic Library, which has been working to rediscover those lost words. To reveal the now-invisible text, the project photographs each page with a series of different lighting strategies, capturing images with visible, infrared, and ultraviolet light. As The Atlantic reports, the project has already produced 30 terabytes worth of images from 74 palimpsests.

Often the text that’s been overwritten is in a language that’s still extant; the researchers have found Arabic, Latin, and Greek texts. (Greek over Greek is a common find.) Some of the texts are valuable for their contents: One Greek text turned out to be a recipe attributed to Hippocrates, for instance.

But the most unique discoveries are the texts of lost languages. Caucasian Albanian disappeared from the area that’s now Azerbaijan before the end of the first millennium A.D. and is known today from only a few texts. The discovery of the erased texts in this language “has brought a 25 percent increase in the readability” of Caucasian Albanian, the linguist Jost Gippert tells The Atlantic, adding basic words like “net” and “fish” to the language’s known vocabulary.

Sometimes discovery means stumbling across a new and fascinating object, but sometimes it means looking more closely and with new eyes at treasures already known.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook