The Tiny Brazilian Frogs Who Can’t Hear Each Other’s Calls

A sad story from the leaf litter of the Atlantic Forest.

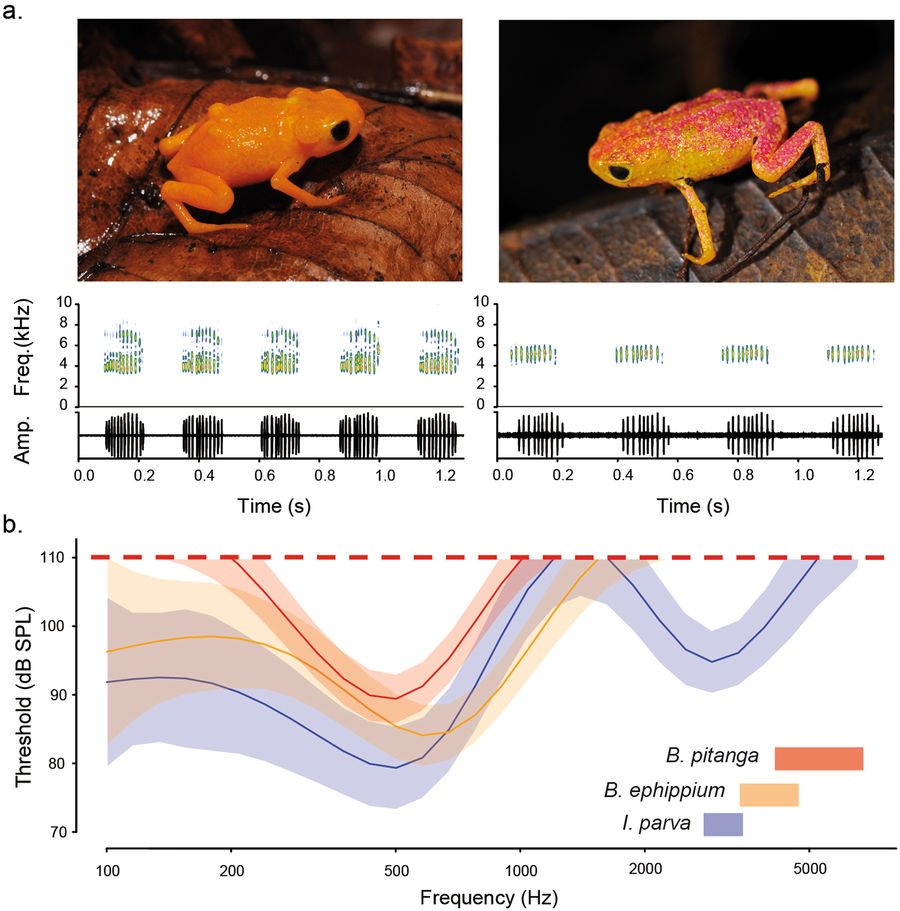

Calling for a mate can be a risky business for the tiny pumpkin toadlet, a minuscule orange frog found in Brazil’s Atlantic Forest. It exposes their location in the leaf litter to predators and parasites, saps their energy, and takes up important time that could be spent looking for food.

An international research team, comprising scientists from Brazil, the United Kingdom, and Denmark, have recently discovered another downside: No matter how loud they call, their frog prince or princess won’t be able to hear them. The researchers have found that two species of these frogs are not able to detect the sound frequencies of their own calls. In this case, the target audience—an attractive fellow amphibian—is entirely unreachable, even while many of the creatures they’d rather not be heard by do hear their cries.

It is surprising, researchers say, that evolution hasn’t stopped the frogs from calling, even while it has made them deaf to one another. More than that, it seems to be a unique scenario in the animal kingdom of a communication signal continuing to be used, even when it’s, well, totally pointless.

“We have never seen this before,” said Jakob Christensen-Dalsgaard, from the University of Southern Denmark, in a statement. Further anatomical studies confirmed what they had observed: that pumpkin toadlets have lost the part of the ear used for high-frequency hearing.

Since these frogs can’t hear one another’s amorous advances, they now have to rely on their other senses to figure out which frog to mate with. They’re an almost luminous shade of orange, which may play a part in how they use visual signals to communicate with each other. When the males are calling, their throats thrum, perhaps constituting another signal. (The frogs are diurnal, and might well be able to see and interpret these signals in the daylight.) If a pulsating gullet does communicate a throaty “hello there,” the accompanying call may, curiously, be a byproduct of the real mating behavior.

And even if their predators do hear them, they may be in for a nasty surprise if they decide to act on it. That dazzling DayGlo hue communicates something to them too: Pumpkin toadlets are extremely toxic. Sometimes actions really do speak louder than words.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook