Tracing the Elusive History of Pier 1’s Ubiquitous ‘Papasan’ Chair

The bowl-shaped seat’s conflicted heritage incorporates the Vietnam War.

In May 2016, a young couple took a spin around Los Angeles in a very unusual mode of transportation: a motorized papasan chair. The two can definitely boast one of the more creative repurposings of this dorm-room go-to, which, when not otherwise transformed into garden planters, solar cookers, or pedicabs, ends up in so many garage sales, Craigslist ads, or dusty corners as the domain of domestic cats.

But how did this cushioned recliner, rounded from rattan and angled atop a matching cylindrical base, find its way into our homes in the first place?

Type papasan.com in your address bar and your browser will redirect you to the website of Pier 1 Imports. The papasan, sometimes called a bowl chair or moon chair, has long been synonymous with the exotic furniture retailer, which sells hundreds of thousands of them each year at its more than 1,000 locations. And the company’s history offers up some clues to the rise of this first-apartment fixture.

According to the International Directory of Company Histories, furniture salesman William Amthor started liquidating extra rattan furniture he had in 1958 at a warehouse—Cost Plus, which grew into Pier 1’s main rival, World Market—along Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco. Inspired by the business, Charles Tandy and Luther Henderson of the Tandy Corporation, later RadioShack, gave Amthor a loan to open a retail shop under the name Cost Plus in 1962 in neighboring San Mateo. By 1966, their operation was renamed Pier 1, importing inexpensive goods from around the world, especially Asia, and marking them up. The resale cost, however, was still cheaper than other American and European furniture at the time, attracting budget-conscious baby boomers looking to furnish their first homes with the hippie chic of “beanbag chairs, love beads, and incense,” as the Pier 1 website tells it.

While Pier 1’s wares may have originally had a countercultural appeal, its signature papasan chair appears to owe its debut to the object of so much countercultural protest: the Vietnam War. Talking to Julie Moran Alterio in N.Y.’s Journal News in 2002, former Pier 1 CEO Martin Girouard said he introduced the papasan shortly after he joined the company in 1975, having noticed a smaller version of the chair when serving in Vietnam. Misty Otto, a former public relations manager for the company, echoed Girouard. Speaking with Georgetown professor Jordan Sand in 2007 for his article, “Tropical Furniture and Bodily Comportment in Colonial Asia,” she indicated, as Sand puts it, that “papasan chairs became popular in the United States after American G.I.s sent to Vietnam found them in Thailand and shipped them home,” a practice other vets have noted online. However, Martin Bureau, a Canadian regional manager for Pier 1, mentioned in 2008 that the company has stocked the chair since 1962, just before the U.S. began escalating troop numbers in Vietnam but over a decade before Girouard claimed its introduction.

Despite its own inconsistent claims, Pier 1 may well have begun selling the papasan in 1962—but its popularity, owing to a Girouard push and G.I.’s greater familiarity with the chair, took off in the mid-1970s.

Some of the earliest evidence for the term papasan chair indeed points to the Vietnam War era, though not quite in Thailand. A 1977 edition of the MAC Flyer, issued by the Military Airlift Command Safety Office, features an installment of Major C.R. Terror, a fictional pilot and his misfit crew whose antics were meant as cautionary, if comic, tales. At a loss for what to get his wife for Christmas, C.R. says: “She’s got that wombat skin coat I brought her back from Athens, the Honda Gold Wing from Tokyo, candlesticks from Bangkok, a giant brass table from Iran, two camel saddles from Turkey, a pair of elephants from Saigon, and a papasan chair from Clark.” (His copilot replies: “Sounds like her apartment must be decorated in ‘contemporary military.’”)

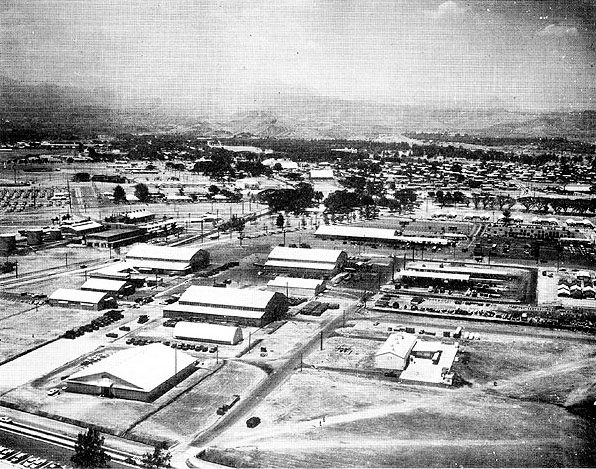

Clark ostensibly refers to the Clark Air Base in Central Luzon, Philippines, now the Clark Freeport Zone. The U.S. has long had a presence in the country, from occupying it after the Spanish-American War to liberating it from Japan in World War II. And during the Vietnam War, Clark Air Base served as a strategic hub for the U.S. Air Force.

Three years before C.R.’s Christmas dilemma, the Central Luzon Regional Agricultural, Commercial, and Industrial Fair published an advertisement for a papasan chair in its 1974 English-language yearbook, suggesting both the item and term were already familiar in the region. But papasan is not a word native to the Philippines. It is a Japanese term for a father or male elder. (Papa is an earlier borrowing from English, while san is an honorific suffix.) U.S. soldiers picked up papasan and mamasan during World War II and spread them throughout the Asia Pacific. Mamasan soon became slang for a madam of a brothel and, come the Vietnam War, papasan was referring to a pimp.

Did American GIs first encounter the luxurious chair amid some of the notorious red-light R & R during the Vietnam War and so dub it the papasan? Professor Sand speculates that the term, as well as the seat’s commodious size and playful form, may well “evoke the sensibilities of a culture of sexual license (and licensed sex), one of the legacies of the free-spending and fraternizing behavior of the military men who were the instruments of U.S. empire in Asia.”

As for the chair itself, its origins in Asia-Pacific culture may be more innocent. South of Luzon is Mindanao, the third major island of the Philippines. There, a woman named Antonette, now living in Dublin, Ireland, remembers the papasan chair—a term she only knew in her native Bisaya as ratan and a chair she didn’t realize existed outside her homeland—as a very typical item in the Filipino homes of her late ‘70s, early ‘80s childhood. Her family had a cushioned one, whose sturdy frame was passed down from her grandfather. “It was in the corner of the veranda. My sisters and I would always fight over who got to sit in it because it’s very relaxing.”

East Asian cultures are not historically chair-sitting, with rattan-based chairs—cool and comfortable in tropical climes, as Antonette noted—becoming especially popular, and increasingly ornate, among Western colonists in the 19th century. Artisans may have specially crafted rattan seating to appeal to Western lifestyles, but Western lifestyles, in turn, variously compelled some East Asian peoples to switch from floor to chair. And at some point in the 20th century, a simple prototype of the papasan—featuring its distinctive ring but much smaller, un-cushioned, and attached to legs—emerges in local rattan vernacular throughout the Asia Pacific.

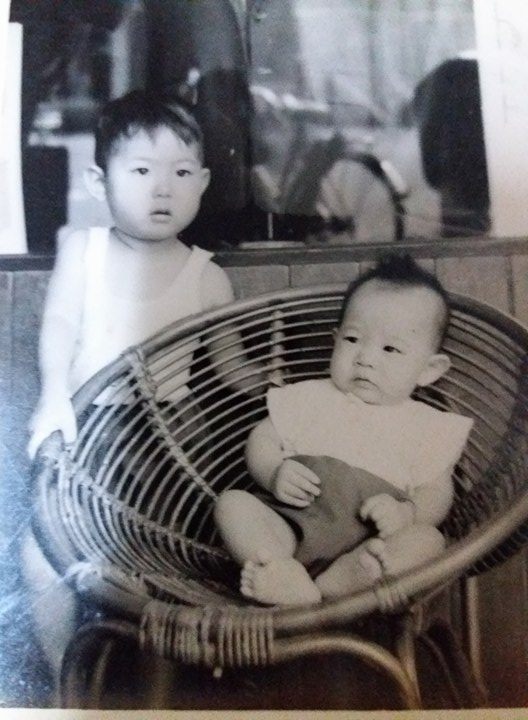

Jordan Sand says over Skype he came across such a potential precursor to the papasan on a trip to Thailand, perhaps like the smaller version Girouard introduced to Pier 1. And over a Facebook chat, a Malaysian woman, Linda P., recalls a papasan-like chair growing up in her native Malacca. The term papasan was new to her, but she recognized its form in the kerusi rotan bulat, literally “round cane chair.” She, along with some fellow Malaysians online, notes that it was a trend in the 1970s to shoot studio portraits of children in these smaller chairs, adding that her mother recalls families ordering them from local rattan furniture shops in the 1960s.

Which is when it seems the papasan indeed came of age: Its basket broadened, welcomed a billowy pillow, and shed legs for a stand. Sand, for one, suspects an enterprising veteran remembered or brought back a basic prototype in the 1960s, expanded it for the American consumer, and marketed it as the exotic-sounding papasan, perhaps with a wartime allusion to its “big daddy” size. Exactly where, when, and by whom the papasan chair first took its modern shape is unclear, but Pier 1 picked it up and popularized it in the U.S., helped along by the 1970s taste in experimental and bohemian design as well as growing financial and environmental pressures to avoid more expensive, consumptive plastics during the oil crisis.

By the late 1970s and 1980s, the papasan had become familiar enough in American family rooms and classified ads (Merriam-Webster finds one in the New Orleans Times-Picayune in 1979). And it endured over the following decades as a fun, affordable, durable, and yet, for all of its remarkable shape, everyday piece of furniture—not so different, despite all the colonialism, conflict, and commercialism in between, from the same chair thousands of miles away in the mountains of Mindanao.

“It was just normal. It lasts long. It’s cheap and people there can afford it,” Antonette says. “It’s funny now looking back, how much we enjoyed it and yet how we didn’t really appreciate it. Now, it’s really nice to remember.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook