In the 1960s, an Artist Imagined an Ever-Changing City That Feels a Lot Like Today

Constant Nieuwenhuys’s “New Babylon” was ahead of its time.

In the winter of 1956, the Dutch artist Constant Nieuwenhuys went to visit his friend, the painter Pinot Gallizio, in his hometown of Alba, Italy. When he got there, though, he found that Gallizio had some other guests. A community of Roma people, who for years had camped out in the town square when they passed through, had been forced by the local government to move their caravans, and had ended up on Gallizio’s property. They had set up camp on a muddy bit of grassland next to a river—in Nieuwenhuys’s words, “the most miserable of patches”—and, in the absence of the city pillars where they normally hung their tents, had built some temporary shelters out of petrol cans and planks.

During his trip, Nieuwenhuys spent a lot of time with the Roma, talking with them and playing flamenco guitar. Seeing the adversity the group faced stirred something in him. As he later recalled, “That was the day I conceived the scheme for a permanent encampment for the [Roma people] of Alba.”

As he pursued this idea—and learned more about the ways in which the Roma themselves approached life—his goal slowly expanded. What if, rather than sheltering one group of people in one static structure, all people pursued a mobile, itinerant, interconnected way of living, and all structures reflected that? What would a city designed for such a lifestyle look like?

Nieuwenhuys wanted to find out. For the next 15 years, the artist dropped everything to work on a set of far-out, multimedia plans for what he called New Babylon, which he described as “a camp for nomads on a planetary scale.” After sitting in storage for decades, the artworks resurfaced last fall in an exhibition at the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, in the Netherlands. According to Laura Stamps, the curator of the exhibition, it was right on time: “What he called [nomadism] has, in a way, become a reality for a number of groups of people,” from freelancers to refugees, she says. “The world is struggling to deal with this.” In her view, Nieuwenhuys’s work can help us explore the consequences and possibilities of our ultra-mobile, connected world.

When he started work on New Babylon, Nieuwenhuys was already a renowned painter and sculptor. He had spent his early career as a founding member of the COBRA collective, a European avant-garde movement inspired chiefly by children’s drawings.

“The child knows no other law than their spontaneous zest for life, and has no other need than to express this,” Nieuwenhuys wrote in the group’s manifesto. He saw this attitude as a good counterpoint to his experiences of the adult world, which, he wrote, had “a morbid atmosphere of inauthenticity, lies and barrenness.”

In 1953, Nieuwenhuys left COBRA and took up with the New Situationists, a posse of artists and activists convinced that those two pursuits were intertwined. With the help of this interdisciplinary group, he further explored his ideas about contemporary life, and began to think about ways to change it.

After a brief stint in London, during which he walked through the recently bombed city every day, he found himself fixated on how urban environments constrain the lifestyles of their citizens. As the curator Mark Wigley later wrote, Nieuwenhuys eventually came to see the modern city as “a thinly disguised mechanism for extracting productivity,” where everything from the overall layout to the structure of individual buildings encouraged particular behavior from people living there.

It was his visit to Alba that brought all of these disparate threads together. If modern cities were built to exclude certain lifestyles, perhaps the key to bringing back the playfulness and freedom of childhood lay not in art, but in architecture. As Nieuwenhuys’s original plan for a permanent Roma encampment became something further-reaching, he quickly abandoned all of his other work, selling his old COBRA paintings to fund this new endeavor. After his friend, the theorist and filmmaker Guy Debord, called the emerging project “Babylon,” Nieuwenhuys stuck a “New” in front of it, in homage to three exciting cities that already existed— New York, New Delhi, and New Orleans. Then he got to work bringing it to life.

In Nieuwenhuys’s vision, New Babylon was a city built for a specific aspect of the human personality: what he called Homo ludens, or “the playful man.” After automation took care of production, he thought, people would be free to be purely creative, and would embrace an environment that enabled this. To that end, every single structure in New Babylon would be made from interconnected units called “sectors.” The citizens of New Babylon could rearrange these sectors at will to create different types of space, and customize the aesthetic environment within each sector—color, temperature, light, texture—with the help of “technical implements” they carried around.

Nieuwenhuys believed that creating these spaces, and exploring those made by others, would scratch a long-dormant itch in the human psyche. In New Babylon, “life is an endless journey across a world that is changing so rapidly that it seems forever other,” he wrote. “Competition disappears… barriers and frontiers also disappear.”

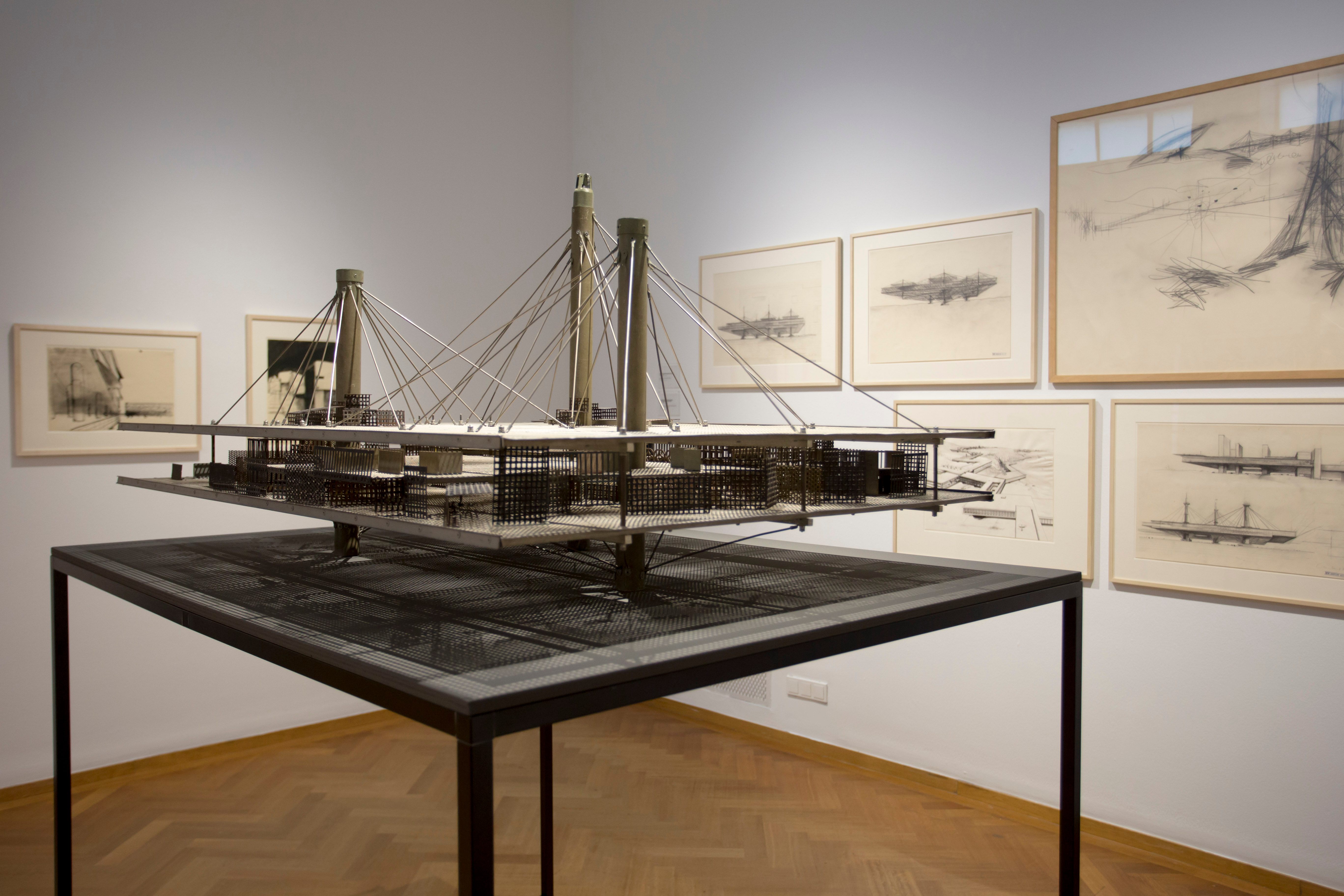

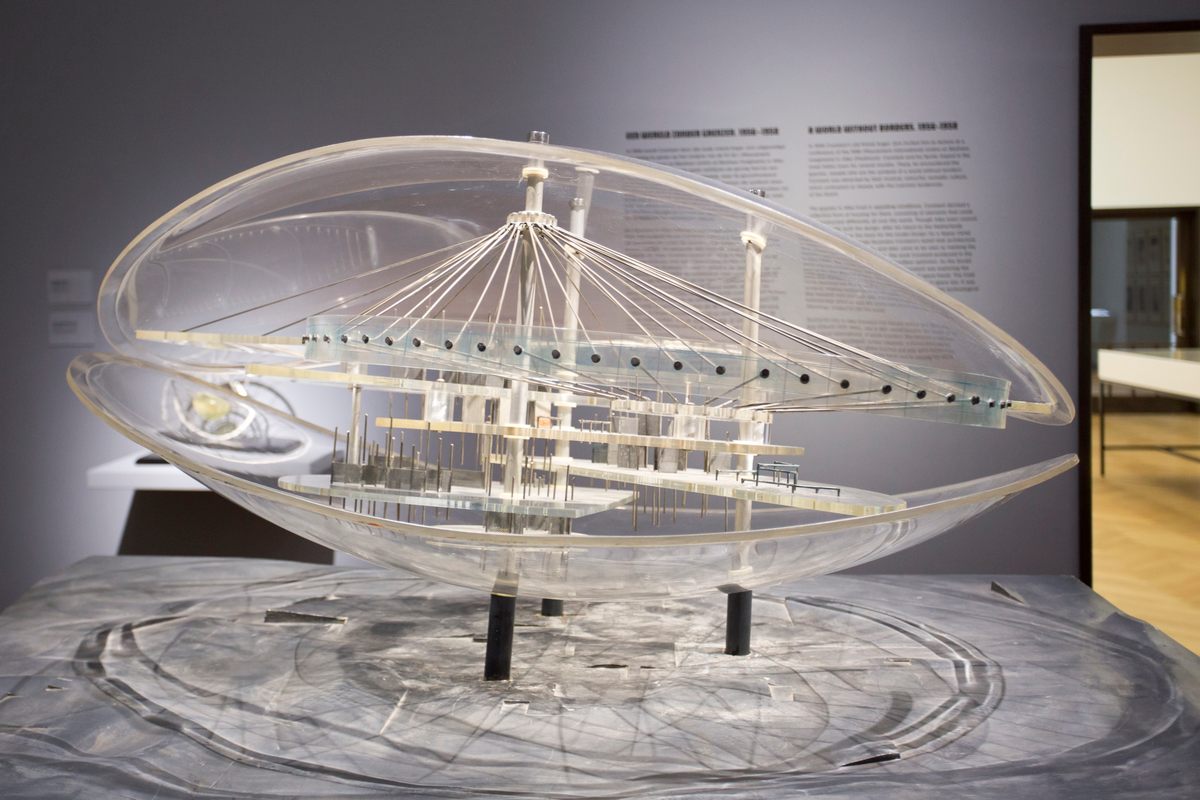

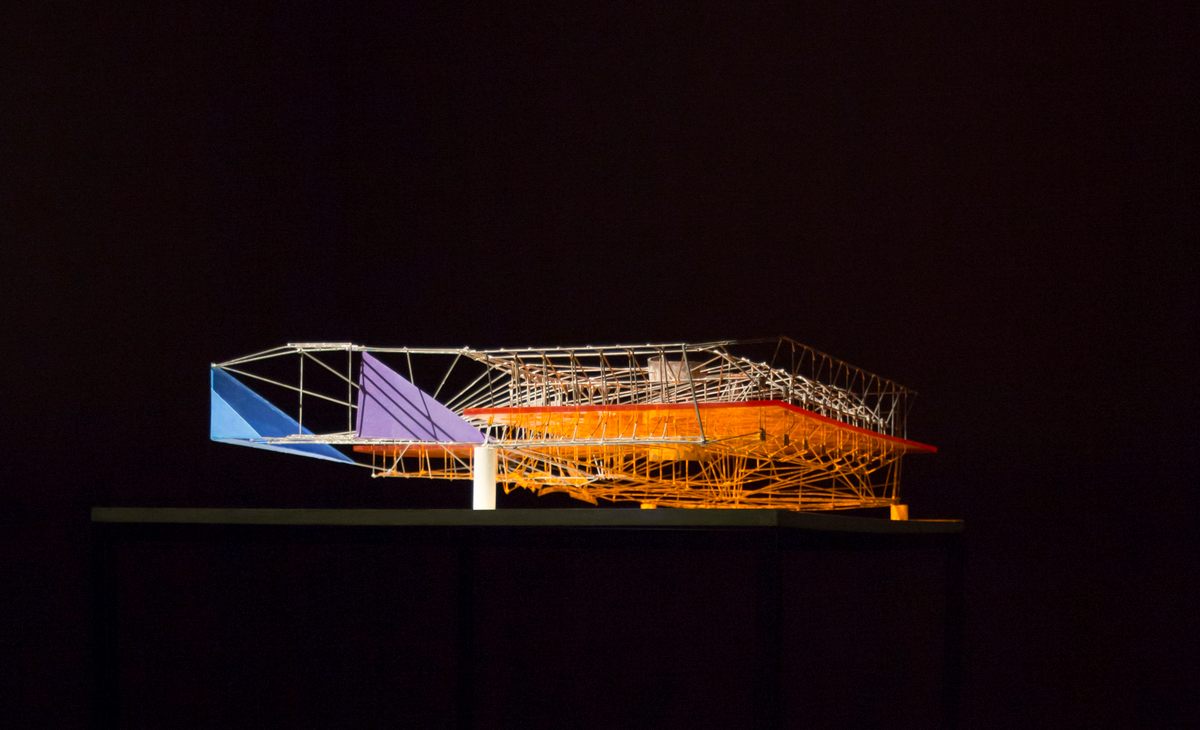

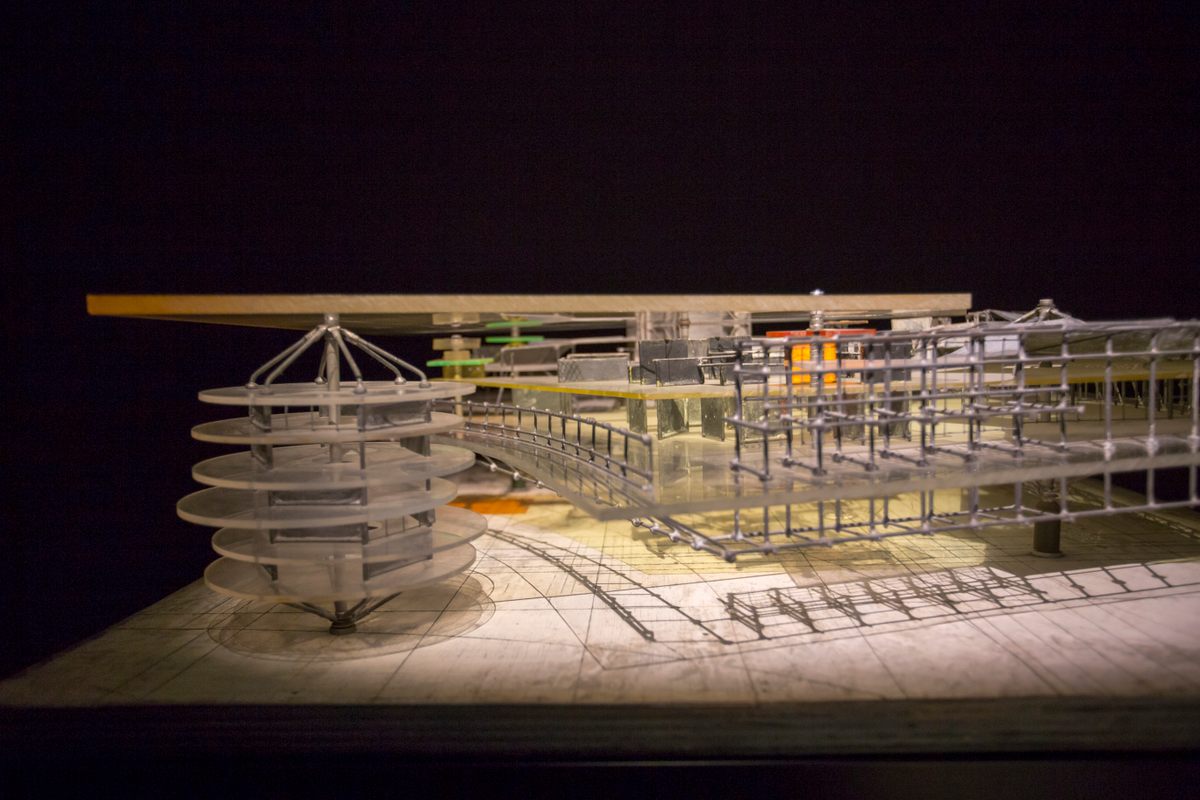

When getting these ideas across proved tricky, Nieuwenhuys marshalled a number of different media types. “He tried a lot of ways to communicate his message—everything that was within his reach,” says Stamps. He constructed miniatures out of steel and plexiglass, so as to reveal layer upon layer of customized city architecture, and placed them over maps of the Netherlands, Europe, and the world. (This photo shows his pet monkey, Joco, perched atop an early miniature.)

He wrote a detailed manifesto, complete with definitions of relevant terms, and profiles of the city’s ideal citizens. He made collages, paintings, drawings, and models of everything he thought the city’s citizens might eventually build: huge helix-shaped towers, graceful atria with circular roofs, precarious stacks of boxy sectors connected by ladders.

In 1960, in a speech to a full house at Amsterdam’s Stedelijk Museum, he outlined his plan in what Wigley calls a “militant tone,” sharing perhaps the most complete iteration of his plans. The interconnected sectors of New Babylon would rest above existing cities, suspended on columns like those the Roma lost when they were kicked out of Alba’s town square. Cars would be relegated to the earth below, left to drive on roads that had been paved atop the ruins of what once were factories, and farms and nature preserves would also dot that lower landscape. All roofs would serve as open-air terraces.

Eventually, Nieuwenhuys even built some immersive environments, which he unveiled at different museum exhibitions. Inside, “you could experience a bit what it was like to be a New Babylonian,” says Stamps. One example, put up again for last year’s Gemeentemuseum exhibition, is “Playful Stairs,” a 1968 work in which thin wooden platforms are suspended from the gallery ceiling by thin black chains. Each hangs at a different level, so as to enable a kind of three-dimensional climbing.

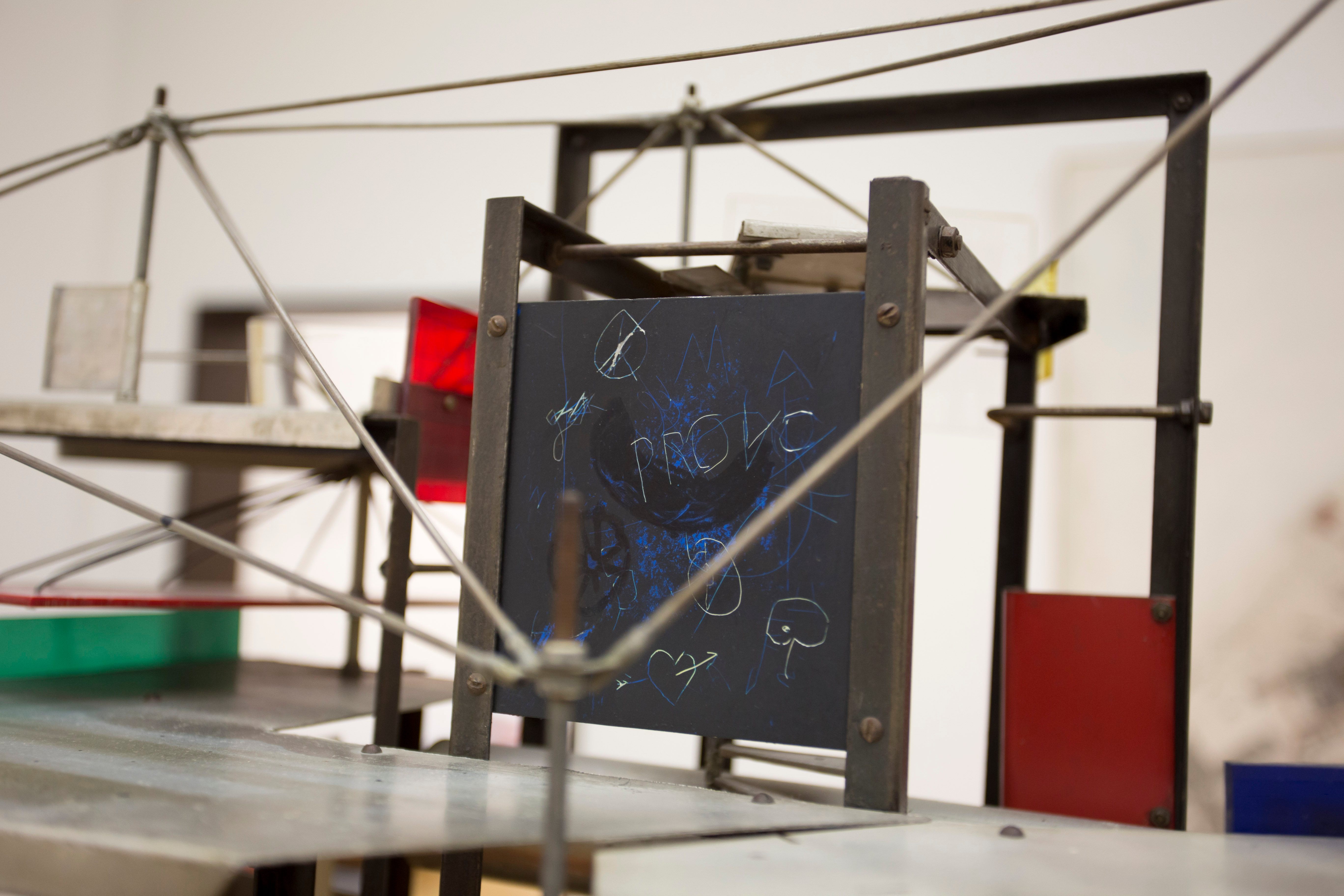

While Nieuwenhuys’s individual architectural decisions may not have held water—many have since come up again, and been roundly critiqued by urban design professionals—their motivating ideas were potent, and by the late 1960s and early 1970s, at least some of his general spirit had rubbed off on the larger populace. Other cultural movements began citing New Babylon as an influence. “They mean to prove Nieuwenhuys right in his prophecy,” one reporter wrote of the Provos, a group of young rabble-rousers who sought to disrupt political traditions and whose slogan was “provoke!” They eventually won a seat on the Amsterdam City Council, where they proceeded to lobby for car-sharing, a public bicycle network, taxes on air pollution, and freely available contraceptives.

And then, in 1974—after 15 years of living and breathing this new world—Nieuwenhuys stopped. At the close of a big exhibition at the Geemeentemuseum Den Haag, he sold all of his New Babylon works to the museum, and returned to painting. “This was as far as I could go,” he said later. “The project exists… It is safely stored away in a museum, waiting for more favorable times.” (Nieuwenhuys passed away in 2005.)

According to Stamps, those times may have finally come. She sees shades of Nieuwenhuys’s ideas in everything from the refugee crisis to smart homes. “The network that Constant envisioned, [with] sectors that were all connected to each other, can be compared with the digital network situation we live in today,” she says. She has also noted an influence on young artists, who she says are drawn to experiential installations and aren’t afraid of political expression. “A lot of artists today feel strong because of a project like this,” she says. Strong—and, Nieuwenhuys would hope, playful, too.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook