Remembering Caspar Milquetoast, the Original Snowflake

He spoke softly and got hit with a big stick.

At one time, the term “milquetoast” was the go-to slam for bullies looking to belittle the meek. And while it sounds like some sort of French bread dish (and that’s no coincidence), the term originated with an early 20th-century comic strip star named Caspar Milquetoast, who through the subtle brutalities of everyday life became a sort of hero for the timid soul.

The original milquetoast was the creation of the illustrator H.T. Webster. Known as “Webby” to his friends, Webster grew up in rural Wisconsin and started his cartooning career in the first decade of the 20th century, with little formal education. He drew sports cartoons for some newspapers out of Denver, Colorado, before moving back to Chicago, Illinois, where he’d briefly attended art school.

During his years in Chicago, Webster produced satirical political cartoons for papers such as the Chicago Inter Ocean, which proved incredibly popular. According to the introduction to 1953’s The Best of H.T. Webster (published a year after his death), Webster’s political cartoons were front-page attractions and even inspired an unsuccessful bill brought before the Illinois legislature to outlaw cartoonists’ unflattering portrayals of state senators and representatives.

His star rising, Webster took a job at the Cincinnati Post around 1908, where he continued his mostly single-frame strips for three more years, after which he headed off to travel the world. His travel journal comics didn’t prove popular enough to finance his globe-trotting adventures, so soon enough Webster found himself back in the States. He went to work in New York, where he began creating illustrations for the Associated Newspapers cartoon syndicate, and later the New York World and the New York Tribune. During this period, Webster moved away from political cartooning, focusing instead on the comedic strips for which he’d eventually come to be known. In a 1949 New Yorker profile, Webster said, “I didn’t like being in hot water, so every now and then, I’d do a little human-interest picture. […] I found that drawing human-interest pictures is what I wanted to do more than anything else.”

Webster’s comics often involved a bucolic, nostalgic moment from childhood or a funny, meaningful, usually banal interaction with the modern world. The term “common foibles” comes to mind. He came to grouping them under titles such as The Thrill That Comes Once in a Lifetime, about life’s little victories; Boyhood Ambitions, which highlighted the lofty dreams of children; and Life’s Darkest Moment, which were about the small indignities we all weather. Webster’s life was often front and center in his work, with many of his childhood strips recalling his Wisconsin upbringing. His Poker Portraits series was based on jokes around the card game that he enjoyed so much, and love of dogs came out in his collection of canine-based gag strips.

As popular as these comics were, it wasn’t until the introduction of Caspar Milquetoast that Webster became a legend.

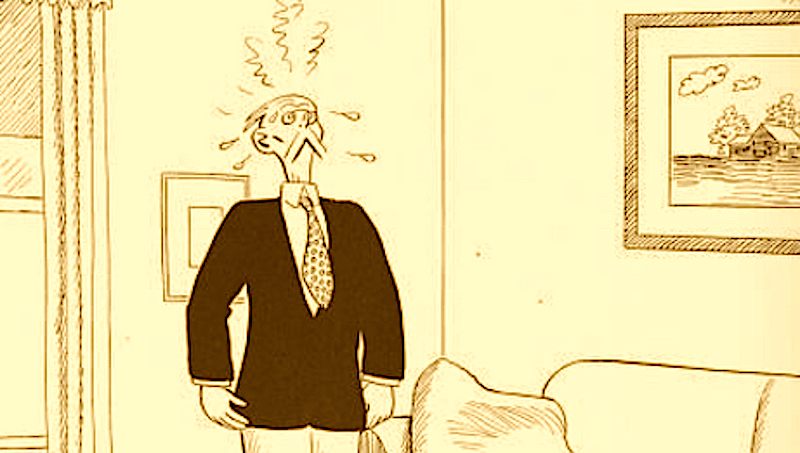

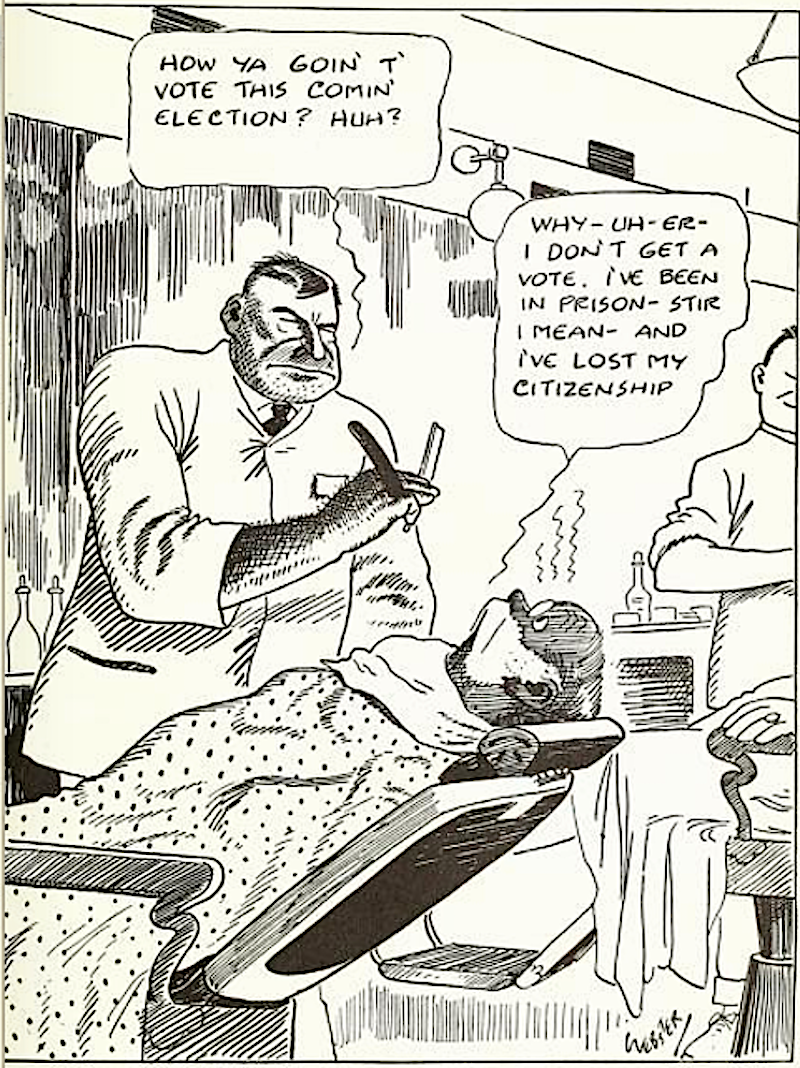

Milquetoast first appeared around 1926, while Webster was working at the World. The character evolved out of an everyman figure that Webster began incorporating into his strips, although he told the New Yorker that even he was a bit unclear about Milquetoast’s exact origin. As he solidified, the character of Milquetoast was drawn as a tall, skinny, older man dressed in a scholarly suit and delicate glasses. His most defining features were his bushy white mustache and little derby hat. Milquetoast was literally a caricature of a wimp.

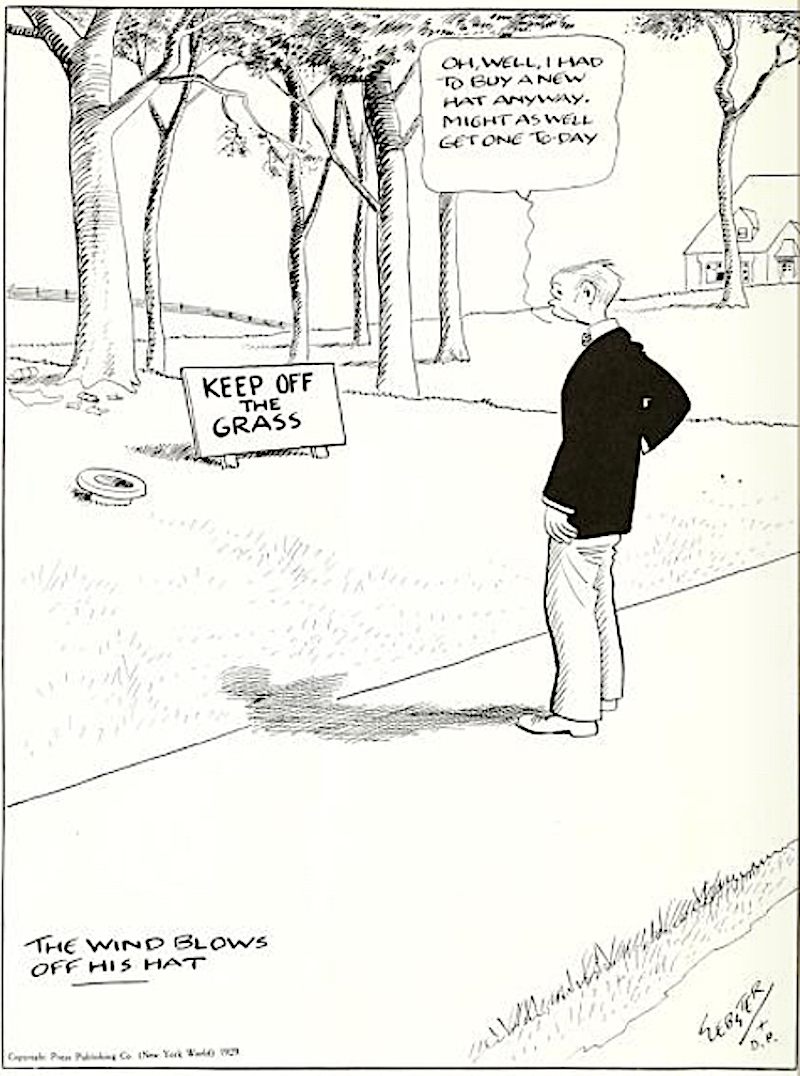

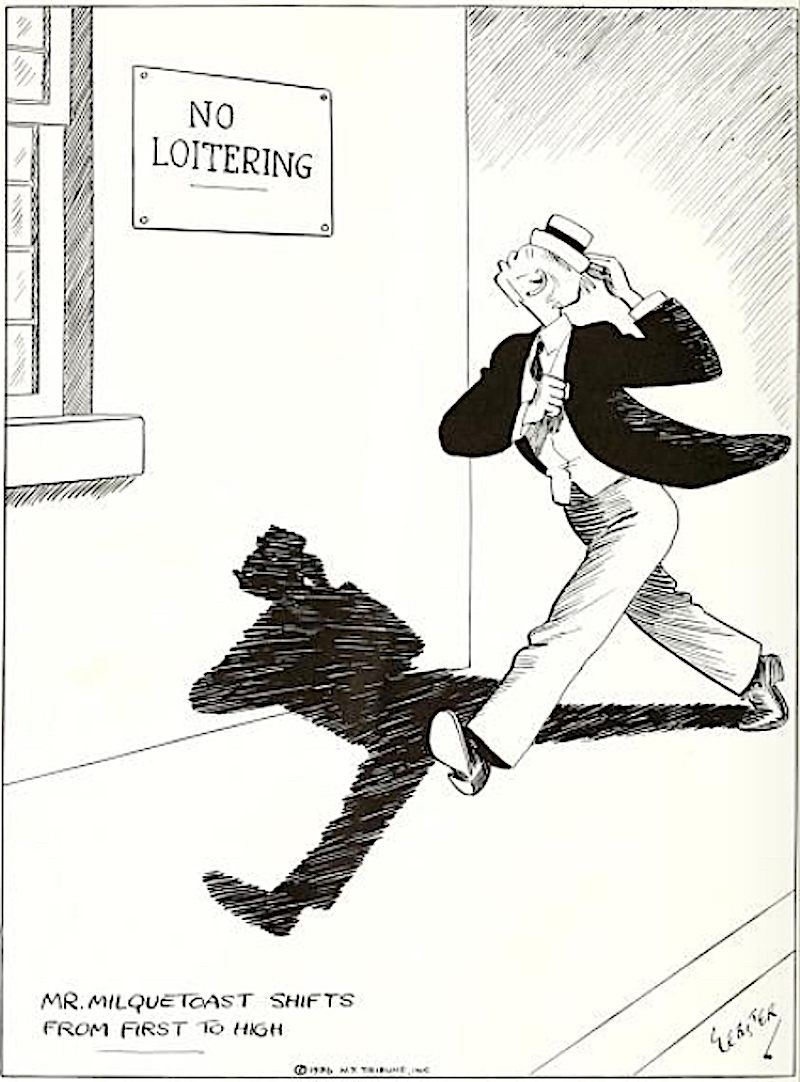

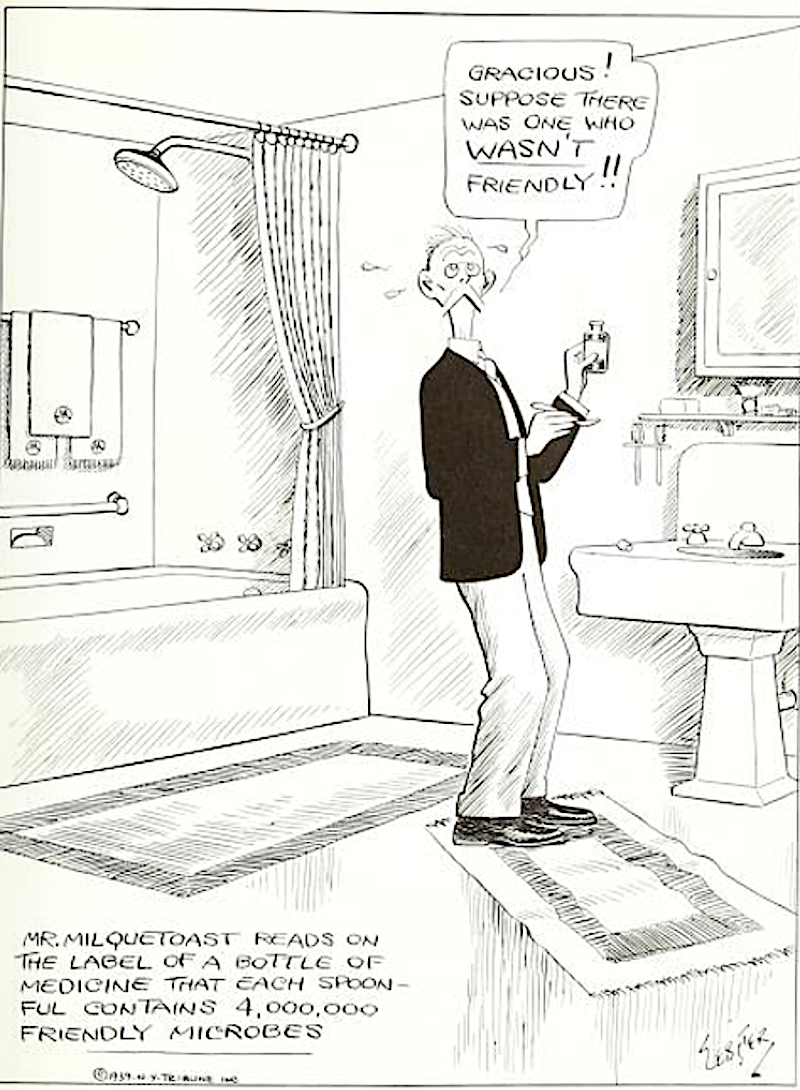

As the character continued to pop up in Webster’s strips, they were eventually grouped together under the title The Timid Soul. Most of the Timid Soul comics involved Milquetoast becoming scared or offended by some seemingly innocuous circumstance, such as finding a blobby piece of art too suggestive, or being too scared to make small talk with a gruff-looking stranger. In a fitting reversal of rough-riding Teddy Roosevelt’s famous quote, Caspar Milquetoast came to be described as someone who “speaks softly and gets hit with a big stick.” The Timid Soul ran a couple of days a week, mixed in with some of Webster’s other strips, and soon gained a popular following.

Webster often modeled Milquetoast’s experiences on his own. Those who knew Webster described him as having a “hypersensitive consideration” of others’ feelings, and an almost pathological respect for authority—so did Milquetoast. When Webster got into golf, or had car troubles, Milquetoast could be expected to go through the same.

In 1931, Webster’s Caspar Milquetoast comics were collected into a book, also titled The Timid Soul. In the New York Times review of the book, the reviewer describes what made the character so popular. “In his black and white delineation of the life and times of Caspar Milquetoast, [Webster] catches virtually all of humanity at one time or another in its most spineless moments.” Caspar Milquetoast, for all of his sniveling wussiness, embraced a sensitivity and universal weakness that was unlike the macho norms of the early 20th century. “The discovery that there are others just as craven is a sure cure for sensations of inferiority.”

Milquetoast went on to inspire a radio show, and even a television show that ran on the doomed DuMont Network. An article in Time from 1945 began, “Millions of Americans know Caspar Milquetoast as well as they know Tom Sawyer and Andrew Jackson.”

But the most telling sign of the character’s popularity was the adoption of his last name as a generic term for “wuss.” By at least the late 1930s (Merriam-Webster’s marks its first recorded usage in 1935), the term “milquetoast” was being widely used as a general term, outside of its comic strip origins. As Webster’s friend later noted, “Webby lived to see the word ‘milquetoast’ listed and defined in a standard dictionary.” The illustrator continued to produce comics until his death in 1952, but he would never create anything as iconic as Caspar Milquetoast.

The term enjoyed widespread popular usage during the 1930s, ’40s, and ’50s. But judging solely by the number of times it pops up in the New York Times’ archives, “milquetoast” experienced a steep decline in the late 20th century. Today, it sounds almost hilariously anachronistic, especially in the face of more abrasive, but similar, put-downs like “cuck” or “snowflake.”

Despite his mid-century popularity, the character of Caspar Milquetoast has also largely fallen out of the public consciousness. In an age when the basic concepts of sensitivity and thoughtfulness are under scrutiny or attack from seemingly every side, we could use more characters like Milquetoast (albeit updated with evolved views on gender and diversity), who aren’t afraid to own their weakness. As a friend of Webster’s said in the closing bits of the illustrator’s New Yorker profile, “Take a good look at Mr. Milquetoast and you’ll find that the big reason he has such a hard time in this world is that he’s a gentleman. A gentleman with the accent on ‘gentle.’”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook