Leonardo da Vinci Designed a Nightmare Scuba Suit

The perfect summer outfit for your dystopian marine nightmares.

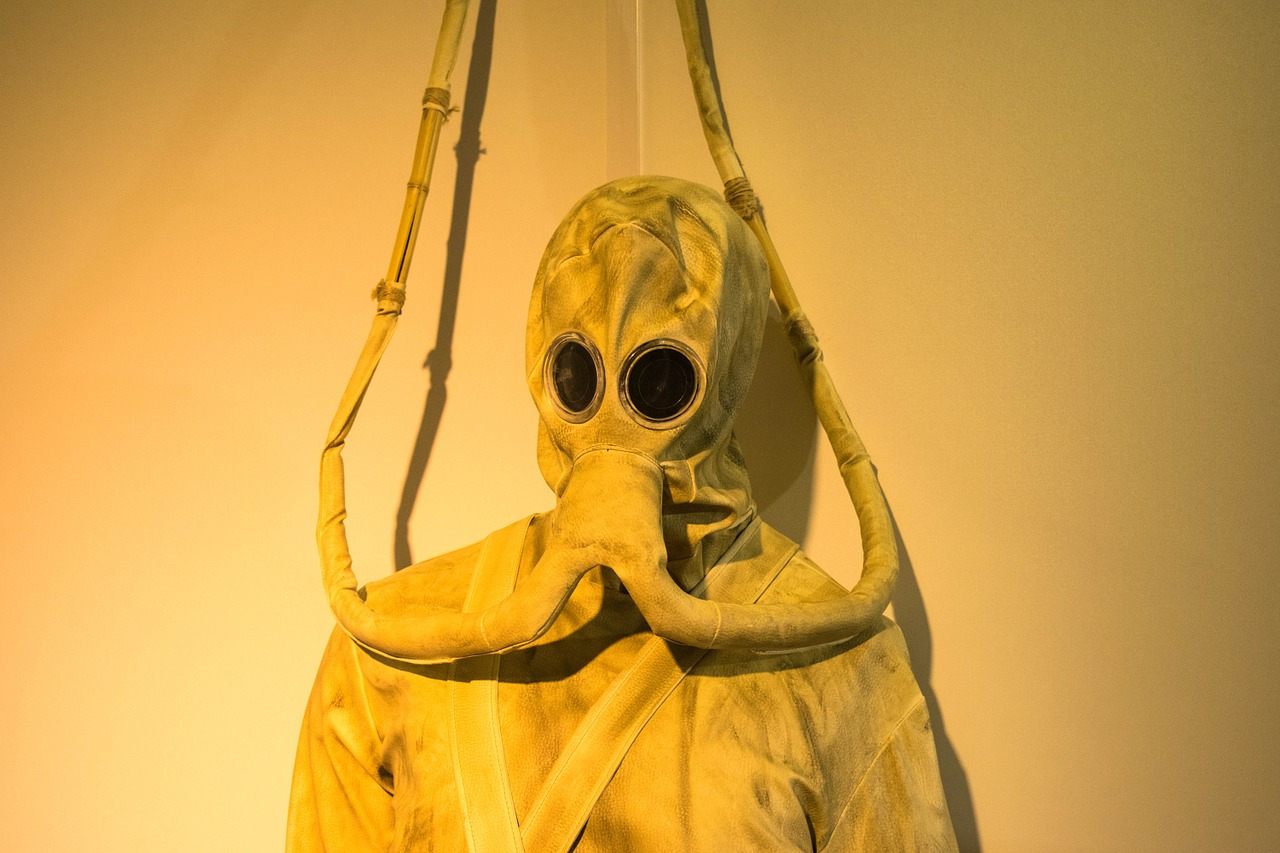

If da Vinci had his way, we’d all be swimming in these. (Photo: Tama66/CC0)

Look at that cloth monstrosity above. Was it designed by an irradiated walrus? A hypochondriac Cthulhu? The creators of an upcoming swamp-themed Fallout sequel?

Despite its alt-future aesthetic, this alarming piece of apparel is actually a 16th-century scuba* suit, dreamt up by none other than Leonardo da Vinci. Although there’s no record that he actually built one himself, da Vinci considered the suit so powerful that he refused to divulge its details, fearing the technology would be abused by the “evil nature of men.”

When we discuss da Vinci’s prescient inventions, we often focus on the high-flying ones—his dreamy, if literally unflappable, bird-shaped ornithopter, or his “aerial screw,” which has spun into the modern helicopter.

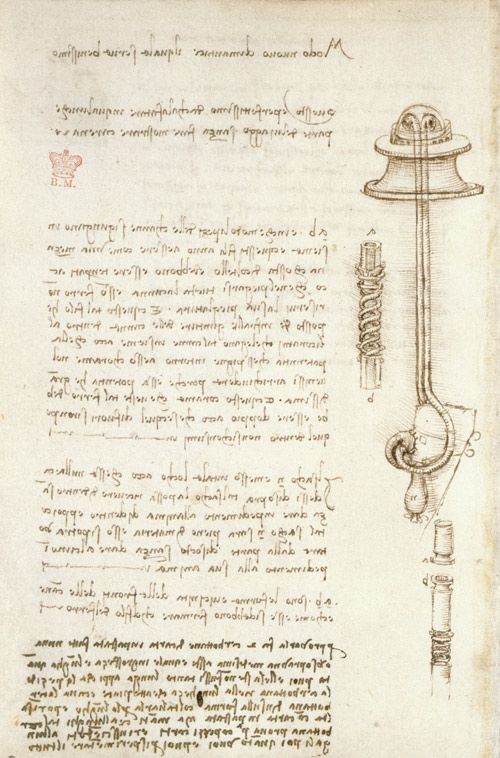

A page from the Codex Arundel, featuring one of da Vinci’s sketches of a diving apparatus. (Image: Leonardo da Vinci/Public Domain)

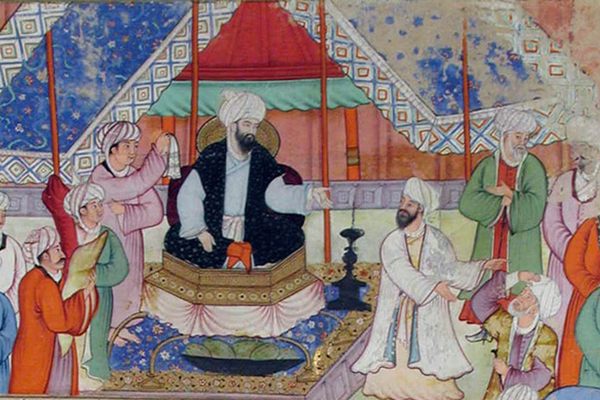

But the polymath’s imagination also dove deep. Although it’s unclear precisely when da Vinci came up with his diving suit, evidence suggests he envisioned it as a military technology, potentially meant to help the Republic of Venice beat the much stronger Ottoman navy. At the turn of the 16th century, much of the Mediterranean Coast was in turmoil, embroiled in a series of international border disputes that kept erupting into full-out war.

Da Vinci, then in his late forties, had been living and working happily in Milan for 17 years, but after French invaders began using a statue of his former patron for target practice, he fled to Venice. There, he found yet more conflict—the floating city had been repeatedly attacked by the Ottoman Empire, who had managed to defeat the entire Venetian naval fleet, taking many prisoners in the process.

Da Vinci was inspired by his new home’s geography, and spent long days rambling the shores, taking note of the water’s properties—its tides, its movements, and the power of its waves. But he was equally inspired by the political situation, and he strove to apply these observations to the cause at hand. “Venice had need at the moment of services such as Leonardo alone could offer,” writes Edward McCurdy in The Mind of Leonardo da Vinci. “The problem which he set himself to tackle was how, in the future, to prevent such incursions.”

The 1499 Battle of Zonchio, between Venice and the Ottoman Empire, as painted by an unknown Venetian artist. (Image: WikiCommons/Public Domain)

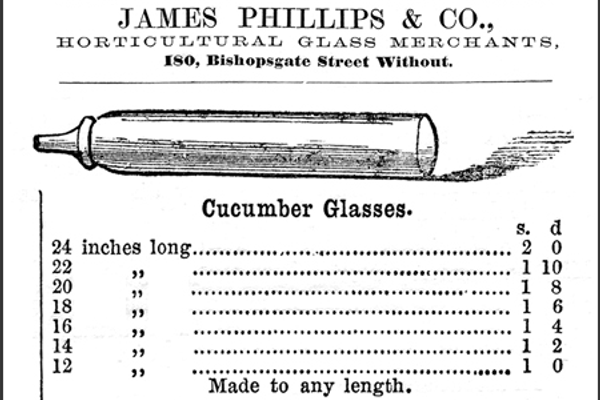

To do this, he took, as usual, to his notebooks. There, tucked within tens of thousands of pages of his lifetime’s achievements, are several drawings of different diving apparatuses, annotated with his signature “mirror writing,” as though reflected on a still lake. The most complete plans show a leather suit and facemask, with goggles and an inflatable wineskin to enable sinking and floating. Two hollow breathing tubes, made of cane and reinforced with steel rings, lead from the diver’s mouth up to the surface of the water—some incarnations show them attached to a floating disc, while others have them leading to a pocket of air trapped by a diving bell. There is even a special pee pouch for the diver, ensuring he can stay down there regardless of whether nature calls.

Some historians think this suit was part of an elaborate plan to attack the Ottoman ships from below, in order to sink them or release prisoners. Others, including McCurdy, say it more likely dates back further, to da Vinci’s time in Milan, in which case he may have intended it to attack Venice instead. (It was a time of tumultuous alliances.)

A full body view of the diving suit, complete with pee pouch and a wineskin for buoyancy. (Photo: Tama66/Public Domain)

But regardless of his intended target, there is little doubt that da Vinci considered the technology too dangerous to describe fully, lest it fall into the wrong hands. “I do not describe my method of remaining underwater for as long a time as I can remain without food,” he wrote elsewhere in his notebooks. “This I do not publish or divulge on account of the evil nature of men who would practice assassinations at the bottom of the seas, by breaking the ships in their lowest parts and sinking them together with the crews who are in them.”

These days, diving suits are usually used for benign purposes—studying marine life, or surfacing buried treasure. But had da Vinci’s designs caught on, we might be looking at a very different underwater landscape. After all, if you saw someone wearing that thing and kicking around the bottom of the sea, you’d flee, right?

*While the suit does not include a portable supply of compressed gas—the technical requirement for a contemporary scuba suit—for the 16th century, a diving bell is pretty close!

Object of Intrigue is a weekly column in which we investigate the story behind a curious item. Is there an object you want to see covered? Email ella@atlasobscura.com.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook