Why British DJs From the ’60s and ’70s Kept Their Best Records Secret

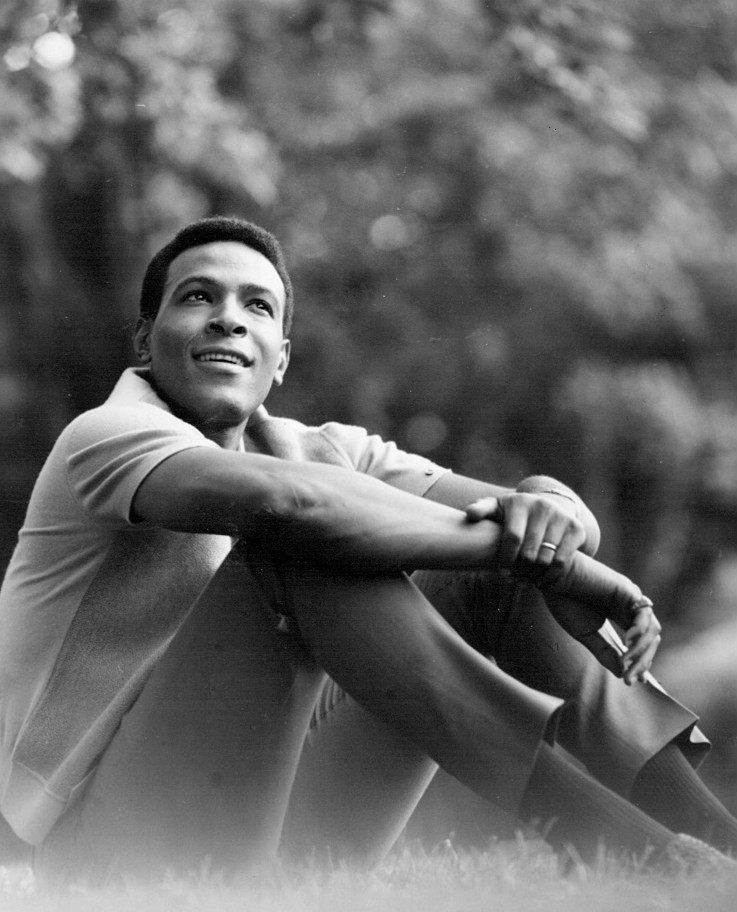

The art of the “cover-up” once led an obscure Marvin Gaye record to be misidentified for decades.

There’s a great Marvin Gaye single from 1967 called “This Love Starved Heart of Mine (It’s Killing Me).” It’s classic Motown. All energy and style and the kind of driving backbeat that made the Motown Sound so iconic. Marvin is giving it his all on this record, his voice a breaking growl, soaring over the music. It’s soul at its finest and we, the lucky listeners, just get to sit back and enjoy it. Or at least, now we do.

Unless they were top brass over at Motown HQ, soul music lovers in the U.S. at the time probably never heard this song. It went unreleased for years, and only reappeared as a bootleg in the late 1970s, with a noticeable difference: Marvin Gaye’s name was nowhere on it. When the record resurfaced years later, it was under the name J.J. Barnes, a purposeful deception by obsessive record collectors and DJs known as a “cover-up.”

The practice of the cover-up most likely began in the 1950s with Jamaican DJs, who took their huge, booming sound systems, complete with generators, turntables, and speakers, to parties to play the newest releases. These events were largely grassroots, for-the-people sorts of things—street parties crowded with dancers all looking to hear the newest releases played on the loudest systems. But over time, many Jamaican DJs of this era pivoted from playing records to pressing them. Suddenly these sound systems weren’t just a party, they were a business. They charged admission, provided food and drinks, and played records straight from their own labels.

But what if a great song didn’t happen to be on your label? What if you still wanted to get people crowding into your spot, but without putting money in some other company’s pocket? Well, “DJs could keep their goodies secret by covering up,” notes Jean Oliver-Cretara, a music professor at The New School who researches Jamaican music and DJs. They could obscure the label, a trick known as white-labeling, or they could rename the album, changing the title or the artist or both to disguise it. Later, as migration brought an influx of Jamaicans to England, the practice spread among DJs, eventually finding a home in the U.K.-based underground scene known as Northern Soul.

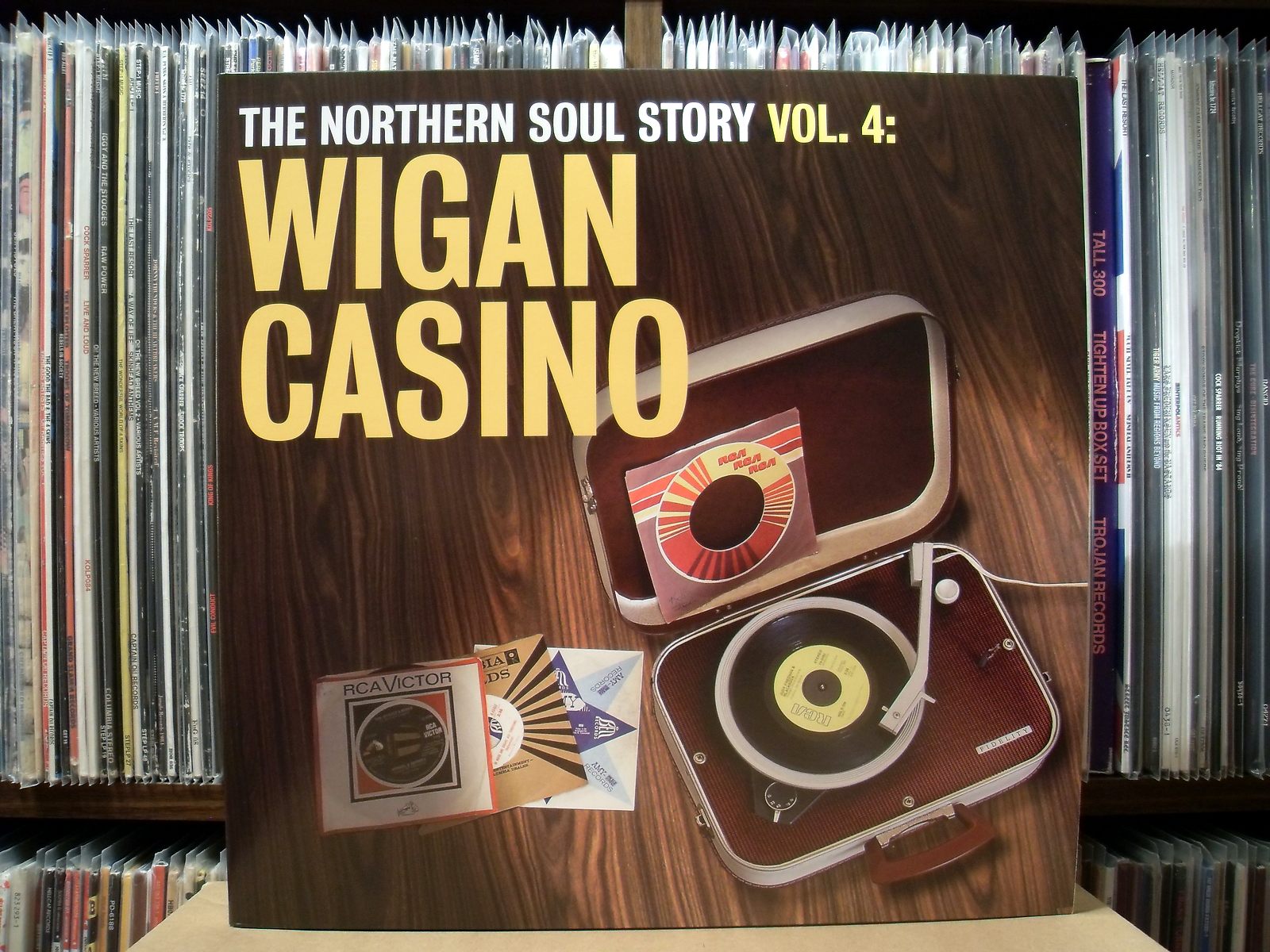

The Northern Soul scene was all about the sound, and not just any sound. Songs had to have two key elements. First, they needed those raw-edged, dance-fueling beats that were packing dance floors an ocean away in the United States. Second, they had to be rare. Oh, you’ve got that extremely popular new Junior Walker and the All Stars single? Good for you. You can keep it. For the Northern Soul scene, obscurity was popularity, explains Abigail Gardner, a music and media professor at the University of Gloucestershire. “DJs would be chasing the most obscure records and maintaining their status as ‘players,’” she says.

Northern Soul’s exacting tastes meant the hunt was always on to find the rarest of the rare. It also meant a dud in the U.S. could mean a hit in the U.K. Some tiny label churning out releases that only saw regional success meant more to Northern Soul DJs than any major Motown hit. Rob Bellars, a DJ at the famed dance club The Twisted Wheel in Manchester in the 1960s and ‘70s, used to send away for American records that hadn’t made their way overseas yet, hoping to put something unique on rotation at the Wheel. “When you wrote to a company for a record and they said it was out of stock,” Bellars explains in the book The Story of Northern Soul: A Definitive History of the Dance Scene That Refuses to Die, “you knew there were a lot of people getting in on the act.”

DJs would do whatever it took to keep their finds a secret, which often meant putting some records in a sort of witness relocation. They’d give the record a false identity by cutting off its label and replacing it with the label of an easy-to-find one. Or, they might label it as a different artist all together. “You hold things close,” as Oliver-Cretara puts it. “Those records are your cards, you don’t show that off. You have to hide your sources.”

The subterfuge served two purposes: it kept the record off of a rival DJ’s playlist, and it kept it out of the reach of bootleggers who could otherwise copy and flood the market with that used-to-be-rare 45. So your Vickie Baines record became a Christine Cooper; your Billy Watkins an H.B. Barnum; and your Marvin Gaye a J.J. Barnes.

Oliver-Cretara also notes the practice may have had roots in something much more basic than preserving secrecy: money. Record labels couldn’t always release a single exactly when or where they wanted. Maybe there was an up-and-comer whose records could be huge in England, but who wants to get their hands dirty with the ins and outs of international contracts? Just cover-up the artist, box up the records, and hello international seller. What the artist doesn’t know won’t hurt them. (At least one artist did fight back in a way, though. Oliver-Cretara tells the story of the Jamaican percussionist Bongo Herman, who upon seeing his records being played and sold under another name in the U.K., bought the entire box of cover-ups and shipped them back to his house).

It ultimately may be impossible to pin down exactly why and how Marvin Gaye’s “This Love Starved Heart of Mine” got the cover-up treatment. One thing we know for certain, though, is that this particular Marvin Gaye record went unreleased, gathering dust on the Motown shelves, for almost 30 years. “When you consider the number of phenomenal people working for us and the high level of energy, we probably passed on more hit records in a week than most labels do in a year,” as Motown founder Berry Gordy put it in the liner notes of 1994’s Love Starved Heart: Rare and Unreleased, a Marvin Gaye rarities collection that includes the label’s official release of the song. For whatever reason, this one just didn’t make the cut at the time. That’s showbiz.

The story of how the record came to make its unofficial debut in late-1970s U.K. dance halls is murkier. It could have happened when Richard Searling, a Northern Soul DJ who spun at the Wigan Casino in the 1970s and ‘80s, discovered an acetate, or test pressing, of the record in 1979. That’s the story related in Kev Roberts’ book, The Northern Soul Top 500. Alternatively, the pressing could have come from a bootleg tape. Or, as one theory goes, it wasn’t actually Searling at all who found it, but another DJ altogether.

Here’s what we do know: The copy that found its way onto English turntables in the 1970s was one that didn’t have Gaye’s name on it. Officially untitled, the record came to be known in clubs as “It’s Killing Me,” and later bootleg versions listed the artist as J.J. Barnes. There’s a bit of a joke buried in the choice of Barnes, too, since he was a singer-songwriter on the roster of Motown rival Golden World records, a label known for promoting sound-alike artists designed to compete with Motown greats. J.J. Barnes was the Pepsi to Gaye’s Coke.

For many, record collecting is a labor of love. It’s combing through dusty old stacks of forgotten songs and singers, hoping to bring them back to life for the length of a song. If you’re a part of a scene that treasures obscurity, it can also be an obsession. The spy games of the era of record cover-ups were definitely a bit of both.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook