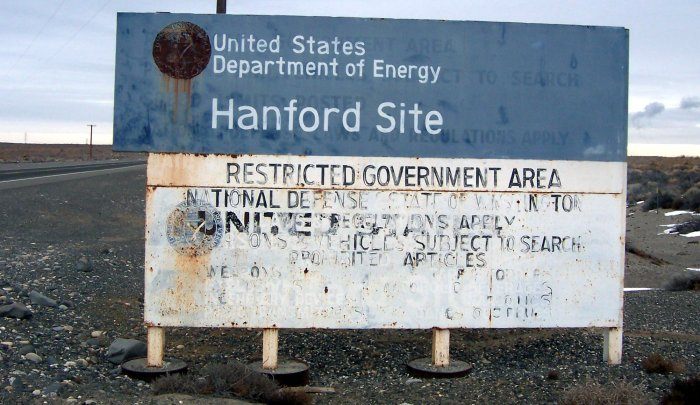

What It Took to Demolish the Most Infamous Room at the Hanford Nuclear Site

After 40 years, the spot where Harold R. McCluskey became the “Atomic Man” has finally been torn down.

Earlier this month, workers at Washington state’s Hanford Site, the most radioactively contaminated place in the United States, noticed that a section of underground tunnel at the facility had collapsed, creating a large hole roughly 20 feet across. The discovery led to a small crisis for the workers, who are tasked with clean-up and demolition at Hanford. In a separate incident, one worker was subsequently found to have radioactive material on their clothing, sparking calls for an investigation into any further contamination from the incident.

This sort of problem is typical at the Cold War-era Hanford Site, once the source of most of America’s plutonium. Today, Hanford is an environmental minefield that continues to create unique problems for the people trying to clean it up.

“We do learn things on the fly, and sometimes we have to stop and take a look at it and readjust accordingly,” says Mark Heeter, a public affairs specialist with the U.S. Department of Energy’s Richland Operations Office. There just isn’t a guidebook on how to safely demolish the site, so the project often has to stop and reassess when, say, a tunnel full of radioactive waste suddenly opens up. “We’re at the end of this 20-year effort to get this complex of buildings taken down,” says Heeter.

The Hanford Site was first established in 1943, as part of the Manhattan Project. The huge site, covering some 580 square miles of land, was selected for its remote location and its proximity to the Columbia River, which could be used to provide power and cooling. Hanford would end up producing about two-thirds of the plutonium used in America’s nuclear stockpile, including the material used in the Trinity nuclear weapons tests, and in Fat Man, the bomb dropped on Nagasaki at the end World War II. During the Cold War, the site continued to grow, adding a number of nuclear reactors and plutonium processing facilities. By the time parts of the sprawling facility were beginning to be decommissioned in the 1960s, it consisted of thousands of buildings.

At the heart of the site, and its complicated demolition, is the Plutonium Finishing Plant, where fissile material was extracted, refined, and prepared for use. This central complex of four main buildings, plus dozens of smaller support structures, was also the site of one of the most infamous incidents in Hanford’s history.

In August of 1976, a technician named Harold R. McCluskey was working with a byproduct of plutonium known as americium when a chemical reaction occurred, exploding the glove box he was working in and peppering McCluskey with shards of glass, metal, and radioactive material. Doctors would eventually determine that McCluskey had been exposed to some 500 times the safe levels of radiation, a level of exposure no human being had ever before survived. He was quickly placed into isolation, cleaned, and treated. Miraculously, the radiation in McCluskey’s body eventually dissipated to safe levels, but until his death in 1987, he was known as the “Atomic Man,” and often had to convince people that it was safe to be around him.

After the explosion, the Americium Recovery Facility was closed and renamed the “McCluskey Room.” As one of the most iconic and dangerous spaces on the Hanford Site, it makes a great case study in the challenges inherent in demolition and clean-up efforts across the facility.

“It was highly contaminated, and plutonium is a flighty material,” says Heeter. “The greatest threat it poses is through airborne contamination.” That means just entering the McCluskey Room required every person to be outfitted in full radiation suits. According to Heeter, workers had to first remove all of the contaminated equipment from the facility, including huge metal glove boxes like the one that exploded on McCluskey. Then they had to spray a special kind of fixative that helped bond the radioactive material to the surfaces. Only after all of these precautions were in place could the actual demolition begin.

Thanks to this constant need to make things as safe as possible for workers, work at the Hanford Site is anything but speedy. Despite having been closed since 1976, the McCluskey Room wasn’t fully demolished until March of 2017. “Worker innovation and involvement was key to the deactivation, decontamination, decommissioning, and demolition of the McCluskey Room,” says Heeter.

And as the recent tunnel collapse shows, there are still years of work ahead. There are countless issues that continue to plague the clean-up effort. Chief among them are the 56 million gallons of highly toxic nuclear waste held in underground storage tanks at the site. These aging and corroding tanks have sprung leaks on multiple occasions, contaminating soil and groundwater in the area. The current plan is to create a waste disposal center where liquid radioactive material can be vitrified into a solid and buried in a permanent grave. But this facility has yet to be constructed.

Still, there are signs of progress. As Heeter says, in its broadest terms, the clean-up effort is divided into three main sections. The outlying area, called the River Corridor, has already been declared clean. Then there’s the Central Plateau, a 75 square-mile area built at a higher elevation where most of the plutonium was manufactured. Finally there is the Inner Area. This 10 square-mile area inside the Central Plateau is where contamination is the worst, and where clean-up work will continue for the long term. “It’s sort-of concentric circles, and we’re working our way inward,” says Heeter.

Eventually, as more and more of the land is deemed safe, it will ideally be returned to local governance, or be transformed into some kind of protected area. “The goal is to provide as much access as possible,” says Heeter. In 2015, the site was identified as part of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park, and tours of certain parts of it are already available.

As work continues, clean-up technicians at the Hanford Site continue to learn. Heeter says that with the demolition of the McCluskey Room, workers have been able to develop a number of techniques that they will be able to use to empty and deconstruct other highly contaminated parts of the Plutonium Finishing Plant. Clean up of what has been called “America’s Chernobyl” is far from over, and the dangers involved are anything but predictable, but each new crisis is another chance to learn about the consequences of our nuclear heritage.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook