The 1929 Plane-Train Hybrid That Almost Was

It’s a bird! It’s a plane! It’s a… railplane?

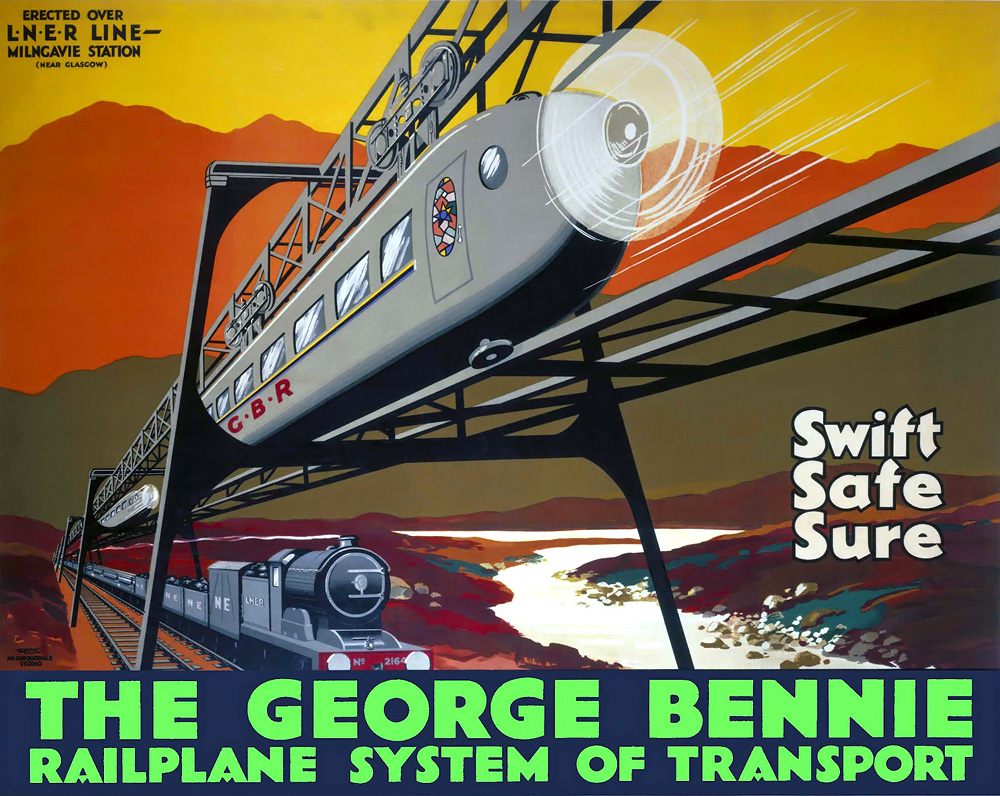

George Bennie wanted to revolutionize transport. In 1920, while examining an early engine, he decided that trains would move more efficiently if they abandoned coal power for propellers. Further: he wanted this new vehicle to ride above the ground, so that other traffic could not slow it down.

Nine years later, in the heat of a massive advertising blitz, Bennie began testing his eponymous George Bennie Railplane outside of Glasgow. Two propellers, one on each side, pushed the Railplane, while two bogies—frameworks with wheels, also known as “trucks”—attached to the top rail held it in place. A series of electric motors provided the power. To brake, the propellers would be reversed, and the Railplane would slow to a halt.

Though the test track proved too small to allow such speeds, Bennie estimated that, in full operation, his invention could reach 120 miles per hour, meaning that the Railplane could shuttle passengers between Glasgow and Edinburgh in 20 minutes—quite a feat, considering even today that trip takes 50 minutes by train.

There were also plans to extend the Railplane into London, even into Paris. One such proposal boasted a three-and-a-half hour trip between London and Glasgow—two hours faster than it takes by rail today.

The fact that Bennie planned to build his Railplane above existing train lines would have also minimized both the cost and the environmental implications of the project, and would have allowed Railplane passengers to avoid the congestion caused by freight trains on the more typical rail lines.

Bennie’s Railplane even promised luxury: it had carpets, plush chairs, carpets, and curtained, stained-glass windows.

But the project never received the financing it needed to take off. Apparently, one reason is that railroad companies feared Bennie’s invention was too efficient, and they fretted over the potential revenue hit their other lines would take.

By 1937, Bennie had spent all of his own money promoting the Railplane, eventually going into bankruptcy. Though the test track has since been scrapped, the shed in which the Railplane was first built still stands today—with a plaque in Bennie’s honor.

Video Wonders are audiovisual offerings that delight, inspire, and entertain. Have you encountered a video we should feature? Email ella@atlasobscura.com.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook