Found: An Invading Snail That Slings Slime at its Prey

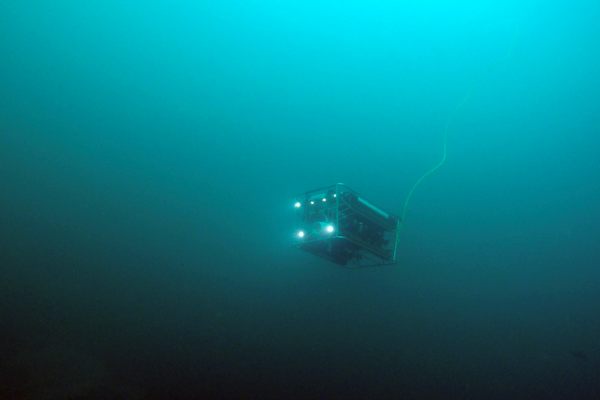

It took up residence on the USNS Vandenberg, which was sunk as an artificial reef.

In 2009, the USNS Vandenberg was sunk into the ocean not far from the Florida Keys. The ship was meant to be an artificial coral reef—a place where divers could explore without endangering the delicate and suffering coral reefs of the area.

In 2012, while examining the reef, scientists spotted three strange snails there. They were members of the worm-snail family, with long, tubular shells that attach to a hard surface and stick there. Two years later, there were tens of thousands of them living on the ship’s hull.

Now, in a new paper published in PeerJ, a team of scientists reports that these worms are a species previously unknown to science, which they have named Thylacodes vandyensis, after the ship’s nickname, the Vandy.

T. vandensis is “kind of cute,” LiveScience reports. On average, the worm-snails are about the length of a finger and are brightly colored, often orange. Their most notable feature, though, may be their mucus glands. “I first got interested in these guys when I saw their giant slime glands,” Dr. Rüdiger Bieler, Curator of Invertebrates at Chicago’s Field Museum, said in a press release.

Most snails use slime as a glide path to move. But these snails aren’t mobile, once they settle in, so what did they need the slime for? It turns out that they use their glands to launch a web of mucus into the water, catching microorganisms in their slimy net and sucking it back in. The snails eat their own mucus along with their prey and recycle it for another slimy go-around.

Bieler and his colleagues studied specimens in museum collection and used DNA sequencing to determine that the Vandy snails were previously unknown. They’re most closely related to species that live in the Pacific, which indicates that they’re likely not native to the area where they were found. Two other invasive species have already been found on the artificial reef: these species probably hitch rides on ship hulls from far away and find places like a newly sunken ship a welcoming home, untroubled by predators or preexisting neighbors.

“These shipwrecks might be acting as stepping-stones for the settlement of invasive species,” one Florida scientist told National Geographic. But they could also be places where scientists could spot early warning signs of an invasion and try to limit the migration of new species into the area, before they start slinging their mucus nets all over.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook