Exploring the Painted Mansions of the Rajasthani Desert

Why gorgeous merchant mansions in the region of Shekhawati sit abandoned and unloved.

A double haveli in Nawalgarh, Shekhawati. (All photos: Eloise Stark)

Shekhawati is a slow-paced region in the Indian state of Rajasthan. To reach it you have to drive several hours through the Thar desert from Delhi or Jaipur. The payoff after this long journey is the region’s glorious collection of elaborately painted residences that date back centuries. These are some of the most unique houses in all of India, and they are largely unknown to the outside world.

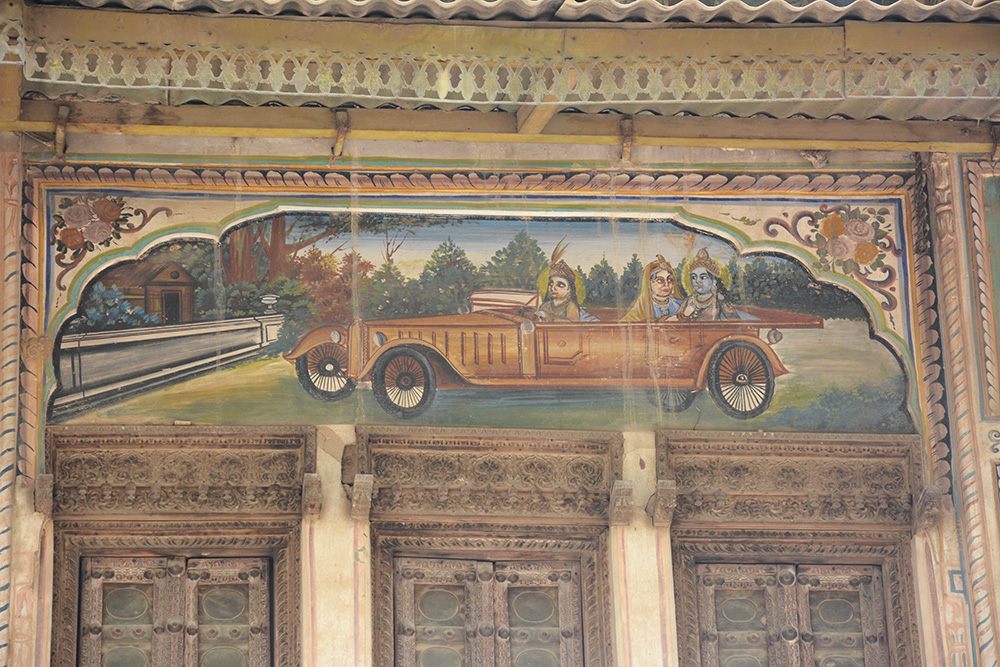

In Shekhawati’s dusty towns, horses still tug carts loaded with vegetables for market. Camels draped with plastic necklaces stroll the streets, looking about as handsome as dromedaries can. But a visitor’s eye is immediately drawn to the grand merchants’ mansions painted with intricate frescoes in vibrant colors that line the streets of many villages here. They are like 3D comic books, adorned inside and out with whimsical scenes of mythology, ancestral battles, and the coming of the Europeans, with their trains, cars and hovercrafts.

The Wright Brothers flying machine, a war and a telephone adorn a haveli.

In Shekhawati, town after town is filled with these frescoes, with 2,000 buildings spread across 5,000 square miles. But with no wide scale effort to conserve them, many are now crumbling into dust. Most of the havelis, as these mansions and townhouses are referred to in India, sit empty.

The structures tell the tale of another time, when Shekhawati was a key stop on the Silk Road. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the region was home to the Marwari community, who made their fortune selling spices, opium and textiles in faraway lands. When the Marwaris returned to their desert homeland, steeped in wealth and fresh dreams, they set to work outdoing each other with their ornate residencies. The paintings had one function, and one alone: to impress those they left behind.

Elephants and a caretaker at the door of a haveli in Nawalgarh.

The paintings are as much a testimony to the patron’s wealth as they are to the imaginations of the artists, at a time where these villages were beginning their first contact with the outside world. The “Britishers” arrived in India in the early 17th century, and echoes of their strange customs began creeping into local art.

The painters in Shekhawati had often never laid eyes on the things they were painting. Their trains look like rows of houses pulled by strings. On one haveli, the Wright brothers’ plane is depicted with the caption: “a boat that flies.”

The hindu god lord Krishna in a speedcar in Fatehpur, Shekhawati.

For generations, Ramesh Jangid’s family have carved the wooden doors and windows of havelis. In the 1980s, his father decided to turn their ancestral home in Nawalgarh into a guesthouse, hoping to attract visitors to the town. “When we first started the guesthouse” says Jangid, “we thought the havelis would never last long. No one was taking care of them.”

The residences are often in the center of town, prime property space, which endangers them. Sometimes, goons from the local land mafia come along at night and demolish an entire haveli by morning, says Jangid.

A woman with a gramophone.

He wouldn’t leave his town for anything, though. “I couldn’t live anywhere else. This place is an open-air art gallery!” he marvels. His favorite haveli is a two-storied house where every room is painted with warm, ochre colors. It’s looked over by a tiny old man in a huge turban. He has been the caretaker for 70 years, and has never even met the Marwari family that owns the haveli.

This is one irony of Shekhawati’s fond paintings of the Europeans. Little did they know the British would bring about the obsolescence of the ancient overland trading routes. As trading centers shifted to the coast, the merchant families left for Calcutta and Bombay, and the havelis lost their prestige.

Paintings featuring Krishna and British women bathing.

For decades, the residences were occupied only by impoverished caretakers, and slowly fell into disrepair. “Locals didn’t see any grandeur in them anymore, explains Joël Cadiou, a French photographer who is renovating one of the havelis. “When something needs repairing, they’re not going to bother doing it nicely, or painting frescoes… they’ll just put cement.”

Cadiou’s mother, Nadine Le Prince, first bought and renovated this residence in the late 1990s, when it was very run down. She had fallen in love with Shekhawati on a backpacking trip 40 years earlier. Today, the house is a cultural center that sees 3,000 visitors a year, from all over the world.

The courtyard of Nadine Le Prince Haveli in Fatehpur, Shekhawati.

The conservation isn’t easy, though. Many of the old techniques have been forgotten. Every year, flooding from the monsoon rains damage the home’s lower paintings. In order to fill the financial black hole of never-ending renovations, Cadiou is transforming the cultural center into a hotel.

“I’m quite pessimistic, even though I want to believe in the project,” he admits. “I don’t want to be the last man standing, I’m not going to watch all the havelis disappear around me. After they’re gone, no one will ever stop in this region again,” he explains, with a mix of bitterness and resignation.

An autorickshaw speeds past a painted haveli in Ramghar, Shekhawati.

Shekhawati’s remaining havelis are an eclectic mix. Some have been repainted in gaudy colours. Others are slowly peeling or fading in the sun. On one haveli, now transformed into a school, the original frescoes have been painted over with pictures of Mickey Mouse.

It might hurt the history lover’s eye now, but just as the historic havelis chronicled the marvels of the industrial revolution, these updated frescoes reflect our new era of globalization.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook