The Split Pants That Are China’s Alternative to Diapers

Kai dang ku might reflect the past and future of toilet training.

In The Travels of Marco Polo, Rustichello da Pisa’s account of the travel tales Marco Polo allegedly recounted during their stint in a Genoan prison together, there are descriptions of “black stones” that could burn like logs to keep homes warm. Coal was used around China in the 13th century, when Travels was written, but largely unknown to Europeans at the time.

There’s a long history of innovations from the Far East that seem unusual to Western eyes but are anything but, and are eventually adopted with verve. Paper, movable type, gunpowder, compasses, porcelain—and split-crotch pants?

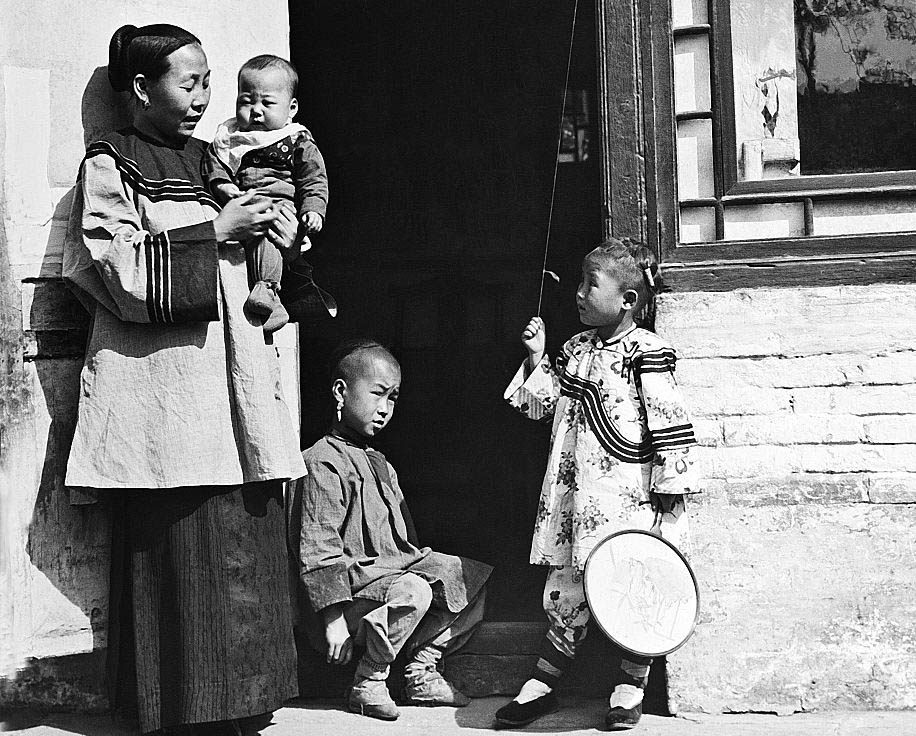

Kai dang ku (开裆裤), which translates literally as “split-crotch-pants,” are the traditional Chinese alternative to diapers: coverings that are open through the middle so toddlers can relieve themselves without obstacle whenever they feel the need. Practical, economical, and still common, kai dang ku provoke all kind of reactions in Western travelers, from shock to wonder and admiration for their environmental benefits. After all, American consumers throw away around 20 billion plastic diapers a year, amounting to 3.5 million tons of waste.

“Chinese babies never wore fabric diapers. Instead they always wore kai dang ku,” wrote Canadian author Jan Wong in Red China Blues, a collection of her cultural awakening when she visited China during the cultural revolution in the 1970s. Split-crotch pants, Wong points out, are way cheaper than diapers, and less water-intensive—especially important in pre-Mao agrarian China, where water was better used to grow crops. “Cotton, water and soap were all scarce items. People weren’t. Someone was always available to ha a Chinese baby,” Wong added. Ha is a short sound for a quite specific act: putting a wobbly toddler in squatting position when nature calls, and cleaning up after them.

Wong’s observation points out a dynamic that long made kai dang ku a welcome option: a communal approach to child-rearing. At least up until a generation ago, most Chinese babies and toddlers were cared for by extended family and the wider community. There was no shortage of people to help, Wong wrote. The use of kai dang ku also presumes that crawling infants, as young as four to six months old, can be active participants in toilet training, much earlier than diaper-wearing Western children, who rarely even attempt it before 18 months of age or later.

Today this Chinese tradition seems prescient, at least among a certain segment of parents in the United States who have signed on to the idea of what’s called elimination communication. Elimination communication refers to practices such as whistles and hisses that may help parents and very young children communicate about the “need to go potty” long before the children can speak. Supporters of this method argue that it helps babies recognize and learn to control their bodily needs at a young age. “This is due, in my opinion, to a conscious recognition of the act, reinforced by a standard position and procedure, whereas diaper babies are encouraged in a way to just let loose whenever,” according to a post on Chengdu Living, a blog written by Americans living in China.

This long-standing sartorial tradition—there is even a Chinese saying, “we have known each other since wearing split-pants”—is fading. “It’s a very recent change,” says Jason Sun from the Museum of Chinese in America. “Kai dang ku were standard up until a generation ago, but today, people from big cities, which is roughly 50 percent of the country, do not use them.”

Economic liberalization has played a role in this: China’s titanic diaper market opened up in 1989, and manufacturers weren’t about to miss out. “Nappies [diapers] were introduced to China by P&G during the 1990s and it has taken a long time for consumers to adopt the products,” market researcher Xu Ruyi recently told the Financial Times. But adopt them they have. The multinational corporations have largely focused on new mothers, not grandmothers, when selling the magical properties of diapers. For example, a 2007 P&G Pampers ad campaign tried to convince mothers that diaper-wearing babies sleep better—and in turn grow stronger and smarter.

China’s one-child policy has played a part, too. “With the one-child policy people started having fewer children and were more able and willing to spend more on the few they had,” says journalist Mei Fong, author of One Child Policy. “So this is the period where the use of diapers and powdered [formula]—seen as more “scientific” and better for child development—really grew rapidly, fostered by the canny power of advertising.” The market economy also put more children in cities, without extended family nearby, and saw parents working longer hours. Beijing Normal University’s Zhao Zhongxin said in a 2004 interview with China Daily that the use of diapers became an indicator of social status.

Among Chinese families who have moved to the United States, few families use kai dang ku, according to Sun. But some American parents are warming to the idea of going diaper-free. Birth Day Presence, a childbirth education studio with locations in tony Park Slope and Soho, New York, started offering elimination communication classes back in 2013. At the beginning most people laughed, founder Jade Shapiro told The New York Times, but one or two couples from every childbirth class signed up. Kai dang ku aren’t exactly coal, paper, or gunpowder just yet, but the final verdict on their diaper-free ethos isn’t in just yet.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook