6 Masterpieces Made While Artists Slept

William Blake’s Five Visionary Heads of Women, drawn from waking dreams late at night. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

This is part one of a 5-part series on sleep and dreams, sponsored by Oso mattresses.

Dreaming—a time when the brain escapes the constraints of consciousness and invents without the mind’s direction—has long played a part in the artistic process. Medieval art based on dreams had a religious, sometimes apocalyptic tone. In the Romantic period, artists used the dark strangeness of the dream state as a way to play with erotic and emotional subtexts. And 20th century Surrealists abstracted dream imagery from reality, painting objects that dripped and swelled, acquiring dimensions not seen in the waking world.

Here are six dream-inspired pieces of art, produced between the 16th and 20th centuries.

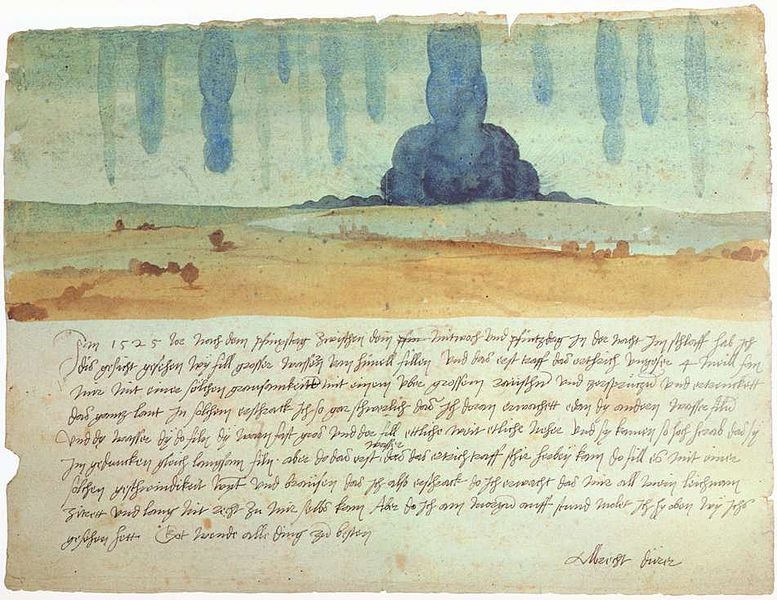

Albrecht Dürer’s Dream Vision, 1525. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

1. Albrecht Dürer, “Dream Vision” (1525)

The German artist filled half of this page with a watercolor, depicting a landscape suffering under an enormous deluge, and half with his written explanation of the dream that inspired the image. He notes that he dreamed of this scene on the night of June 7, 1525. Describing the flood in his vision as “great waters” that fell “from heaven,” accompanied by “wind and roaring,” Dürer reported that this dream affected him physically: “When I awoke my whole body trembled and I could not recover for a long time.” The quickly sketched urgency of this vision makes a striking contrast to Dürer’s painstaking and accomplished engravings, paintings, and woodcuts.

Henry Fuseli’s The Nightmare, 1871. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

2. Henry Fuseli, “The Nightmare” (1781)

The Swiss Romantic painter created a furor when he exhibited this figure of a sleeping woman, visited by a terrifying crouching figure and intruding horse, at London’s Royal Academy in 1782. While the painter was male, and the dreamer in this figure is female, the painting may have been inspired by a fixation Fuseli had developed on a young woman named Anna Landolt. “Fuseli was passionately in love with her, and though he felt unable to tell her this, he recorded…erotic dreams of possessing her while she slept,” writes art historian Edward Burns. Fuseli’s painting—iconic and terrifying—has been widely parodied and imitated.

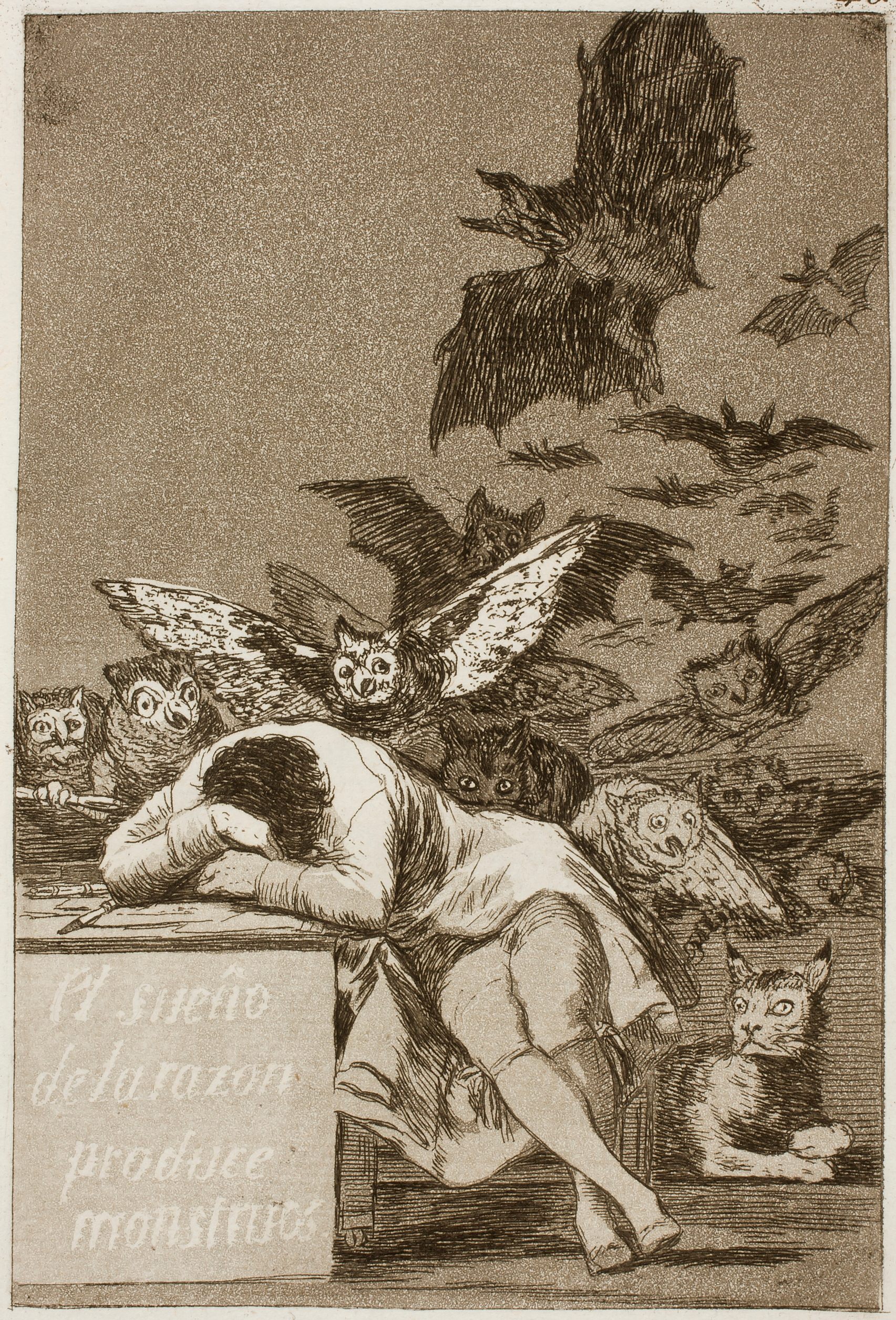

Francisco de Goya y Lucientes’s The Dream of Reason Produces Monsters, 1799. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

3. Francisco de Goya y Lucientes, “The Dream of Reason Produces Monsters” (1799)

This etching is part of the artist’s “Los Caprichos” series: dark satires of the social world of 18th century Spain. A precursor to the more complete “Caprichos” was the less famous “Sueño” (Dream) series, in which Goya worked out some of the ideas that would later appear in the Caprichos etchings. This Capricho (number 43 in the series) appears in a different form in the Sueño drawings. In both versions, the dreaming artist exudes light, a halo that represents rationality; the lurking terrors of superstition linger around the periphery, seeming both attracted and repulsed by the enlightenment that the artist exudes. The title of thisSueño, art historian Frank I. Heckes argues, testifies to the artist’s belief that he, “like mankind in general, [could] only overcome superstition, ignorance, and irrationality by uniting reason with fantasy.”

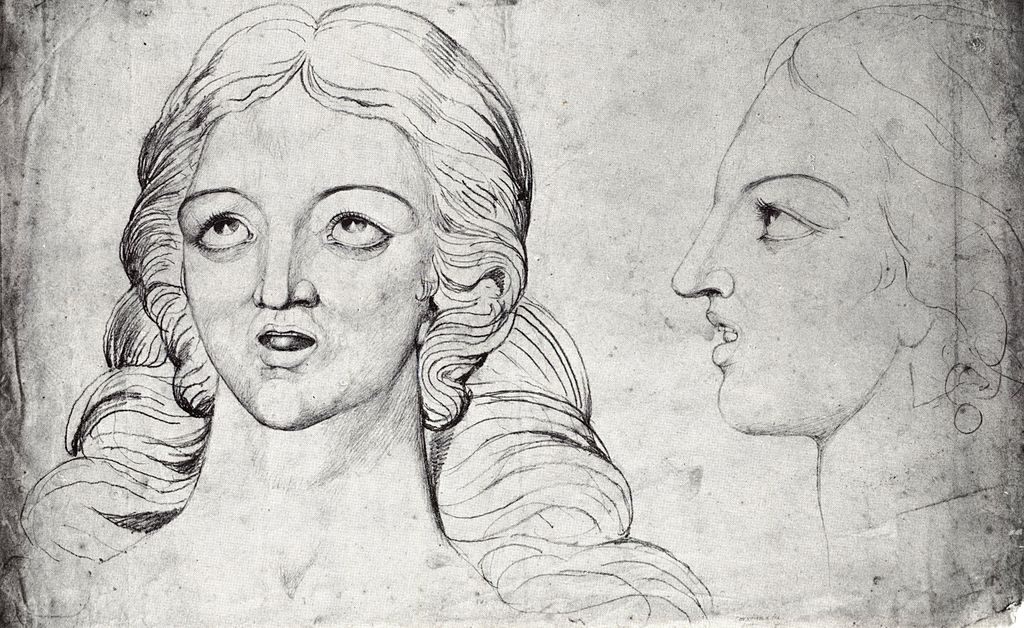

Corinna the Rival of Pindar and Corinna the Grecian Poetess from the Blake-Varley Sketchbook, 1819-1820. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

4. William Blake, “Visionary Heads” (1819-1920)

In 1818, artist and astrologer John Varley, who was a patron of William Blake at the end of his life, asked Blake to embark on this project. Blake claimed to have entertained visions his entire life, and Varley was interested in a particular type of mystical experience: visitations from people long dead. Varley and Blake would sit together, late at night, and Varley would suggest that Blake interview a particular dead luminary. Blake would “see” that person in the room, and begin to speak, and to sketch. Altogether, Blake put together three sketchbooks of people he saw in these waking dreams, including such figures as Milton, Voltaire, King Solomon, Charlemagne, Robin Hood, and William Wallace.

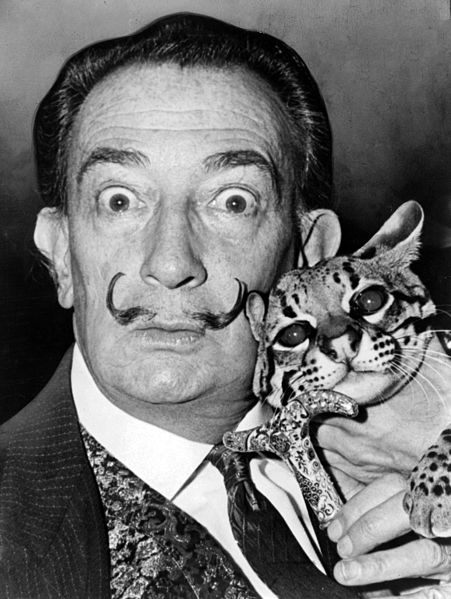

Salvador Dali with an ocelot, 1965. (Photo: Library of Congress)

5. Salvador Dali, “The Dream Approaches” (1932-33)

If previous artists had occasionally sketched or drawn images based on their dreams, the Surrealists systematized an artistic technique for capturing images presented by the dreaming mind. As Deirdre Barrett writes, Dali offered advice about “the cultivation of dreams” in his Fifty Secrets of Master Craftsmanship, advocating that artists try their hardest to exploit the hypnagogic margins between wakefulness and sleep. Sit in an armchair, Dali wrote, and hold a “heavy key…delicately pressed between the extremities of the thumb and the forefinger of the left hand.” When you start to fall asleep for real, his advice went, you’ll drop the key, and it will clang on the upside-down plate you’ve made sure to place on the floor underneath. This will wake you up, so that you remember the images that came to you in that liminal state. Using this technique and others Dali made many paintings featuring dream-like imagery, including this one.

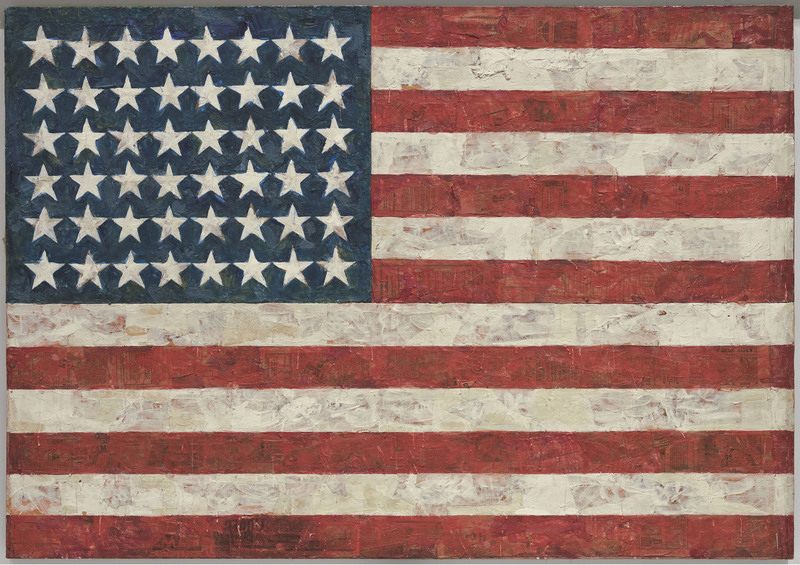

Flag, 1954-55 by Jasper Johns. (Photo: Art © Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, NY/Image: © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY)

6. Jasper Johns, “Flag” (1954-55)

“One night I dreamed that I painted a large American flag,” Jasper Johns said,” and the next morning I got up and I went out and bought the materials to begin it.” The Korean War veteran painted “Flag” at a time when he was trying to break through to new levels of artistic independence; as a Johns biographer, Isabelle Loring Wallace, says, before painting “Flag” Johns had “systematically destroyed all existing work in his possession, vowing that henceforth his art would be free of perceptible debt to other artists.” In 1990, the artist said in an interview that his father had told him when he was a boy that his namesake, Sergeant William Jasper, died keeping an American flag from falling to the ground during a Revolutionary War battle. Johns thought this early impression might have surfaced in his subconscious, resulting in the dream that inspired him to create “Flag.”

Sponsored by Oso mattress. OSO mattress is customizable comfort created with Reverie’s DreamCell(TM) technology. Shop the mattress now to discover the sleep for you.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook